Hypersonic flight is conventionally referred to as the ability to fly at speeds significantly faster than the speed of sound and presents an extraordinary set of technical challenges. As an example, when a space capsule re-enters Earth’s atmosphere, it reaches hypersonic speeds—more than five times the speed of sound—and generates temperatures over 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit on its exterior surface. Designing a thermal protection system to keep astronauts and cargo safe requires an understanding at the molecular level of the complicated physics going on in the gas that flows around the vehicle.

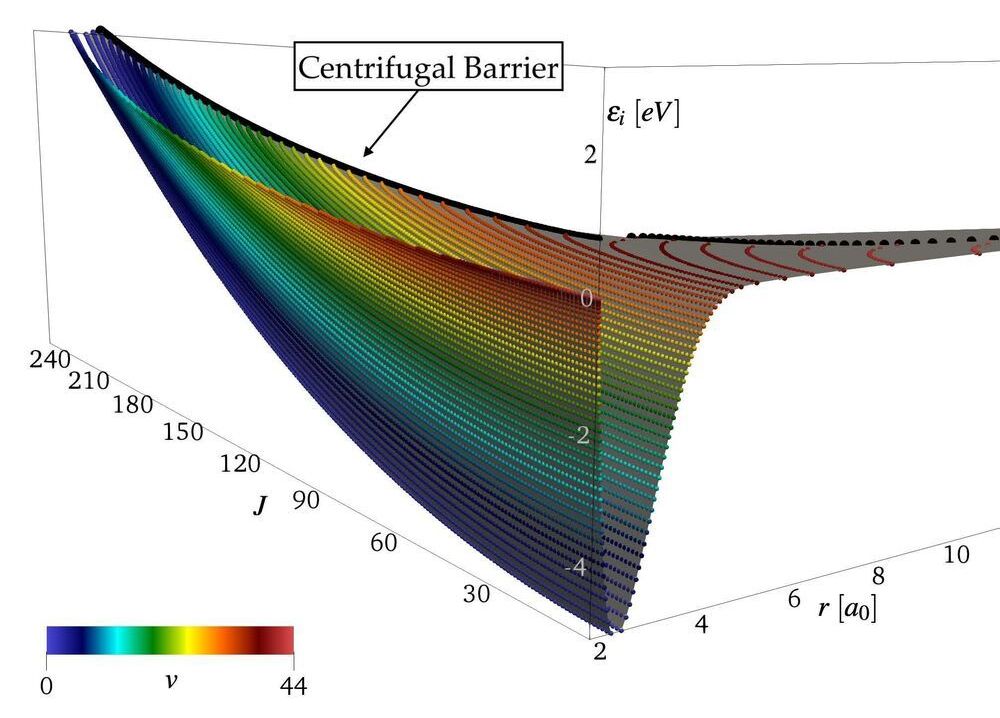

Recent research at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign added new knowledge about the physical phenomena that occur as atoms vibrate, rotate, and collide in this extreme environment.

“Due to the relative velocity of the flow surrounding the vehicle, a shock is formed in front of the capsule. When the gas molecules cross the shock, some of their properties change almost instantaneously. Instead, others don’t have enough time to adjust to the abrupt changes, and they don’t reach their equilibrium values before arriving at the surface of the vehicle. The layer between the shock and heat shield is then found in nonequilibrium. There is a lot that we don’t understand yet about the reactions that happen in this type of flow,” said Simone Venturi. He is a graduate student studying with Marco Panesi in the Department of Aerospace Engineering at UIUC.