Hydrogen is a sustainable source of clean energy that avoids toxic emissions and can add value to multiple sectors in the economy including transportation, power generation, metals manufacturing, among others. Technologies for storing and transporting hydrogen bridge the gap between sustainable energy production and fuel use, and therefore are an essential component of a viable hydrogen economy. But traditional means of storage and transportation are expensive and susceptible to contamination. As a result, researchers are searching for alternative techniques that are reliable, low-cost and simple. More-efficient hydrogen delivery systems would benefit many applications such as stationary power, portable power, and mobile vehicle industries.

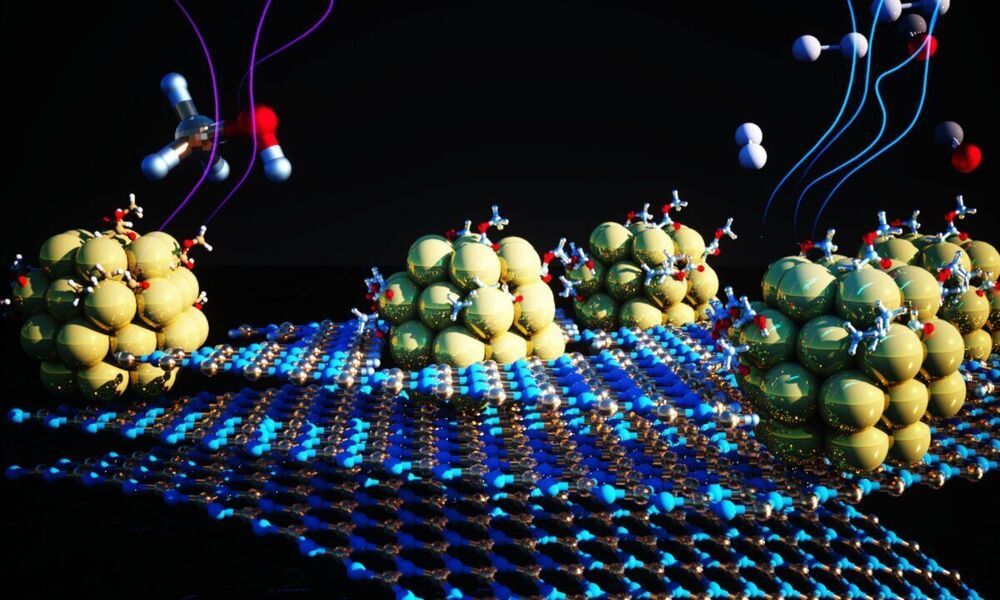

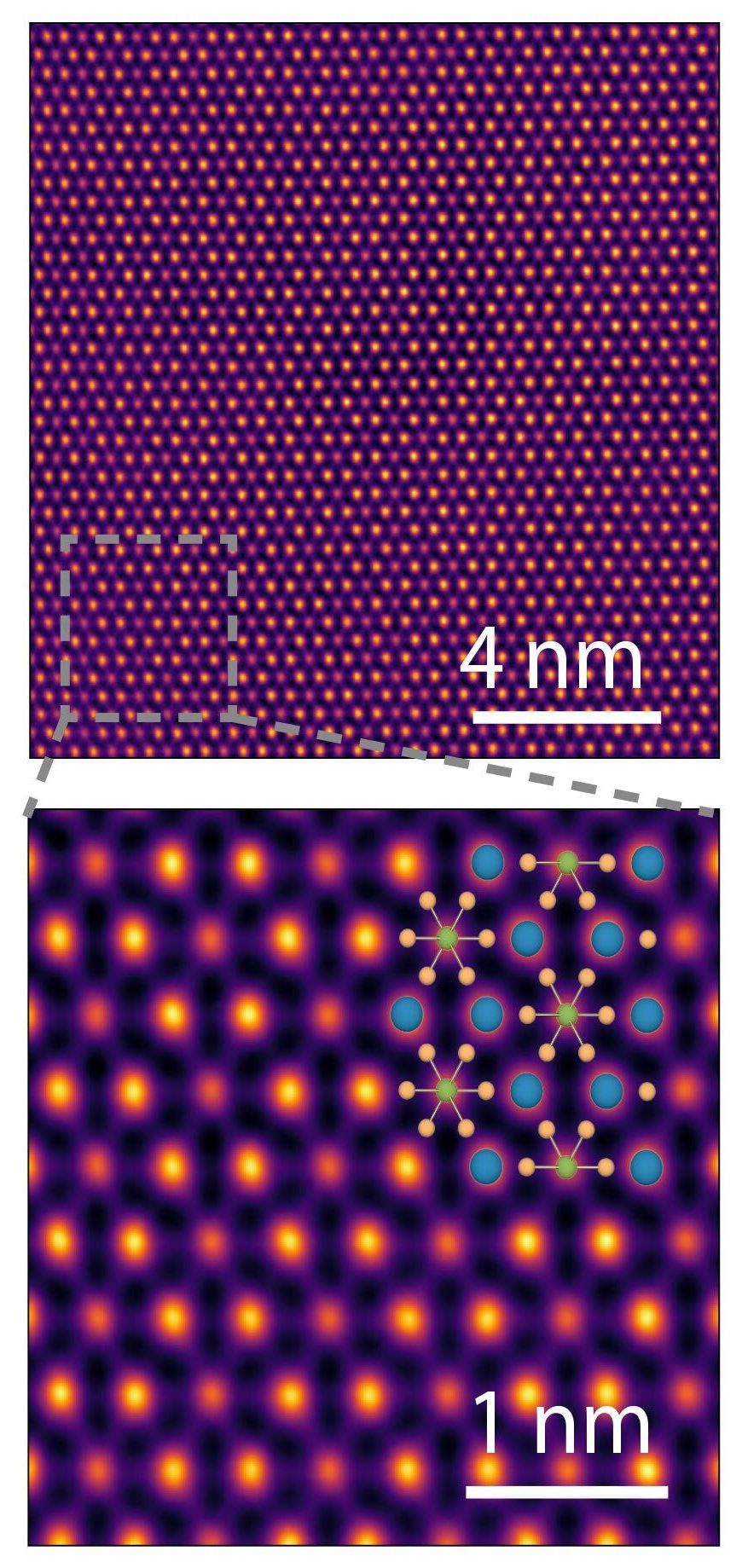

Now, as reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers have designed and synthesized an effective material for speeding up one of the limiting steps in extracting hydrogen from alcohols. The material, a catalyst, is made from tiny clusters of nickel metal anchored on a 2-D substrate. The team led by researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s (Berkeley Lab) Molecular Foundry found that the catalyst could cleanly and efficiently accelerate the reaction that removes hydrogen atoms from a liquid chemical carrier. The material is robust and made from earth-abundant metals rather than existing options made from precious metals, and will help make hydrogen a viable energy source for a wide range of applications.

“We present here not merely a catalyst with higher activity than other nickel catalysts that we tested, for an important renewable energy fuel, but also a broader strategy toward using affordable metals in a broad range of reactions,” said Jeff Urban, the Inorganic Nanostructures Facility director at the Molecular Foundry who led the work. The research is part of the Hydrogen Materials Advanced Research Consortium (HyMARC), a consortium funded by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies Office (EERE). Through this effort, five national laboratories work towards the goal to address the scientific gaps blocking the advancement of solid hydrogen storage materials. Outputs from this work will directly feed into EERE’s H2@Scale vision for affordable hydrogen production, storage, distribution and utilization across multiple sectors in the economy.