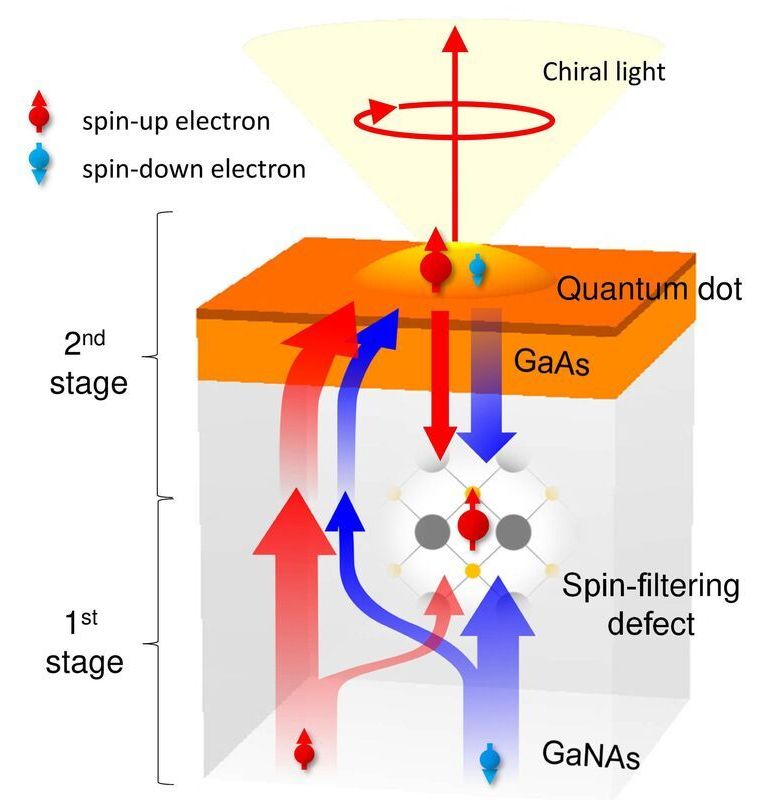

It may be possible in the future to use information technology where electron spin is used to store, process and transfer information in quantum computers. It has long been the goal of scientists to be able to use spin-based quantum information technology at room temperature. A team of researchers from Sweden, Finland and Japan have now constructed a semiconductor component in which information can be efficiently exchanged between electron spin and light at room temperature and above. The new method is described in an article published in Nature Photonics.

It is well known that electrons have a negative charge; they also have another property called spin. This may prove instrumental in the advance of information technology. To put it simply, we can imagine the electron rotating around its own axis, similar to the way in which the Earth rotates around its own axis. Spintronics—a promising candidate for future information technology—uses this quantum property of electrons to store, process and transfer information. This brings important benefits, such as higher speed and lower energy consumption than traditional electronics.

Developments in spintronics in recent decades have been based on the use of metals, and these have been highly significant for the possibility of storing large amounts of data. There would, however, be several advantages in using spintronics based on semiconductors, in the same way that semiconductors form the backbone of today’s electronics and photonics.