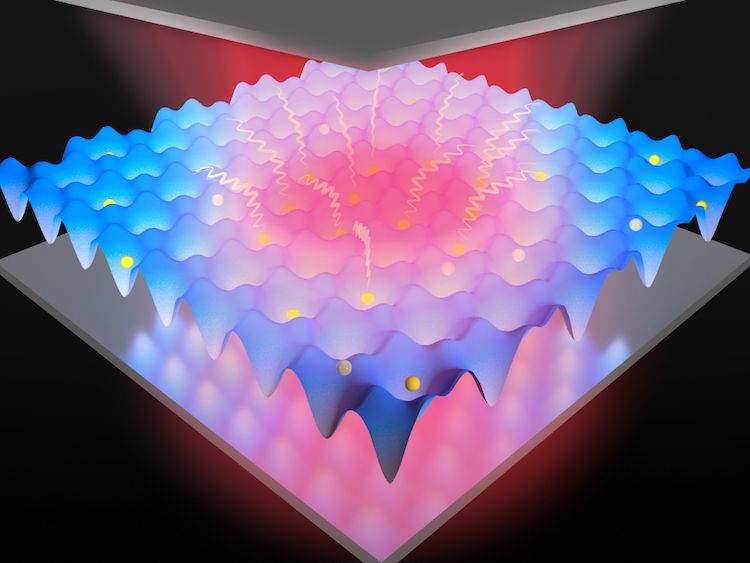

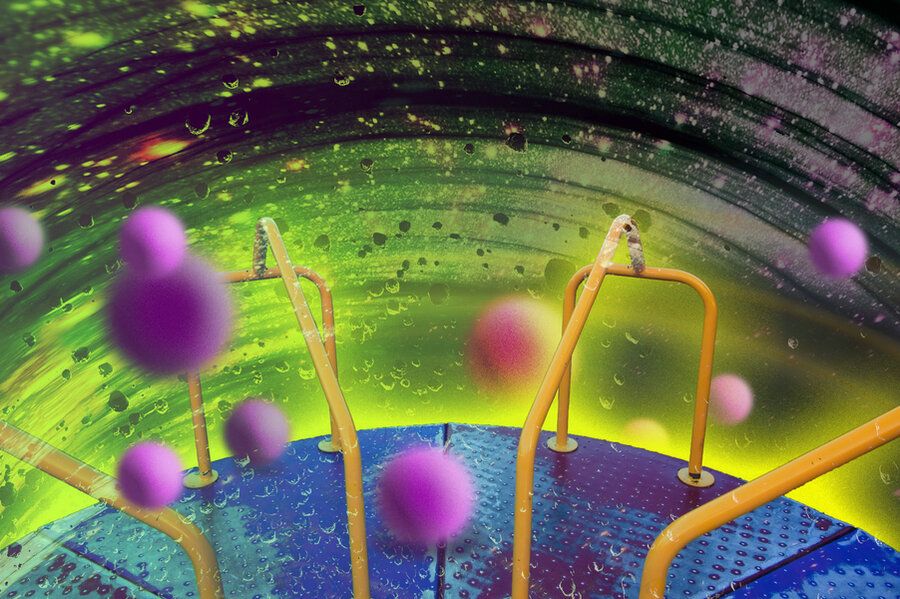

Spin waves could unlock the next generation of computer technology, a new component allows physicists to control them.

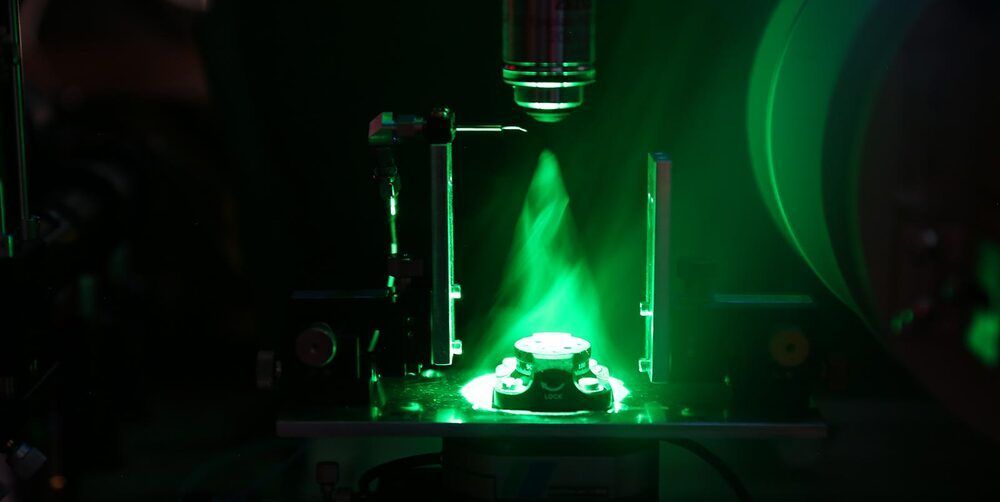

Researchers at Aalto University have developed a new device for spintronics. The results have been published in the journal Nature Communications, and mark a step towards the goal of using spintronics to make computer chips and devices for data processing and communication technology that are small and powerful.

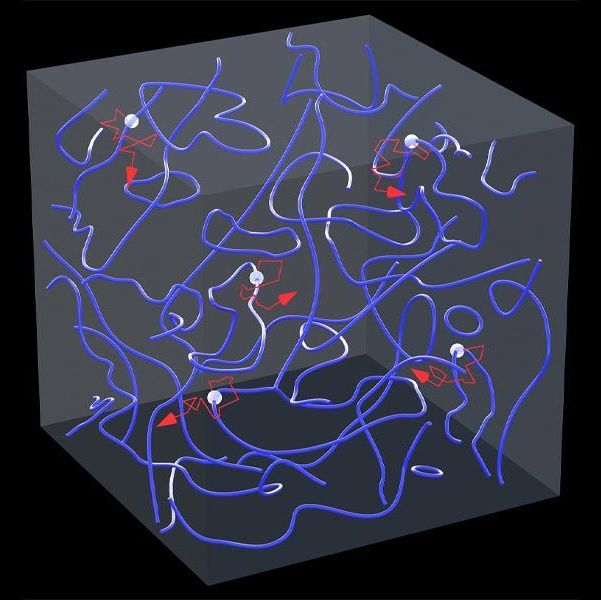

Traditional electronics uses electrical charge to carry out computations that power most of our day-to-day technology. However, engineers are unable to make electronics do calculations faster, as moving charge creates heat, and we’re at the limits of how small and fast chips can get before overheating. Because electronics can’t be made smaller, there are concerns that computers won’t be able to get more powerful and cheaper at the same rate they have been for the past 7 decades. This is where spintronics comes in.