Seeing is believing.

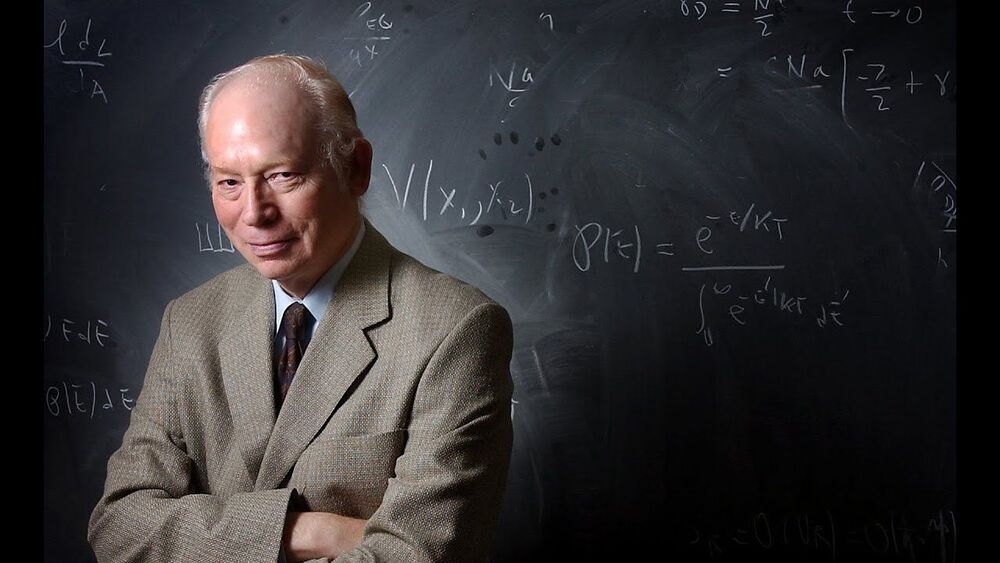

Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg was one of the world’s foremost theoretical physicists and a passionate advocate for science. Among his many influential contributions is the co-discovery of the electroweak theory that unifies electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force, a central pillar in the Standard Model of Particle Physics. Join Brian Greene and physicist John Preskill as they pay tribute to Steven Weinberg and his profound contributions to science.

This program is part of the Big Ideas Series, made possible with support from the John Templeton Foundation.

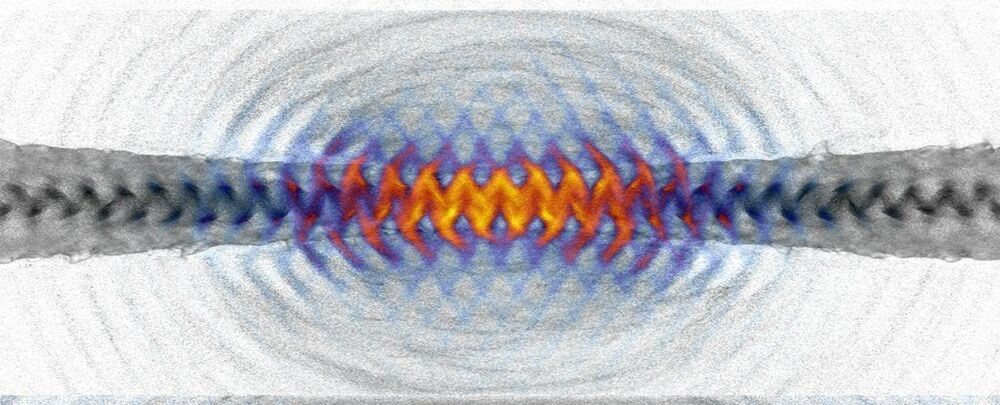

A new study by scientists has demonstrated how researchers may be able to create an accelerating jet of antimatter from light.

A team of physicists has shown that high-intensity lasers can be used to generate colliding gamma photons – the most energetic wavelengths of light – to produce electron-positron pairs. This, they say, could help us understand the environments around some of the Universe’s most extreme objects: neutron stars.

The process of creating a matter-antimatter pair of particles – an electron and a positron – from photons is called the Breit-Wheeler process, and it’s extremely difficult to achieve experimentally.

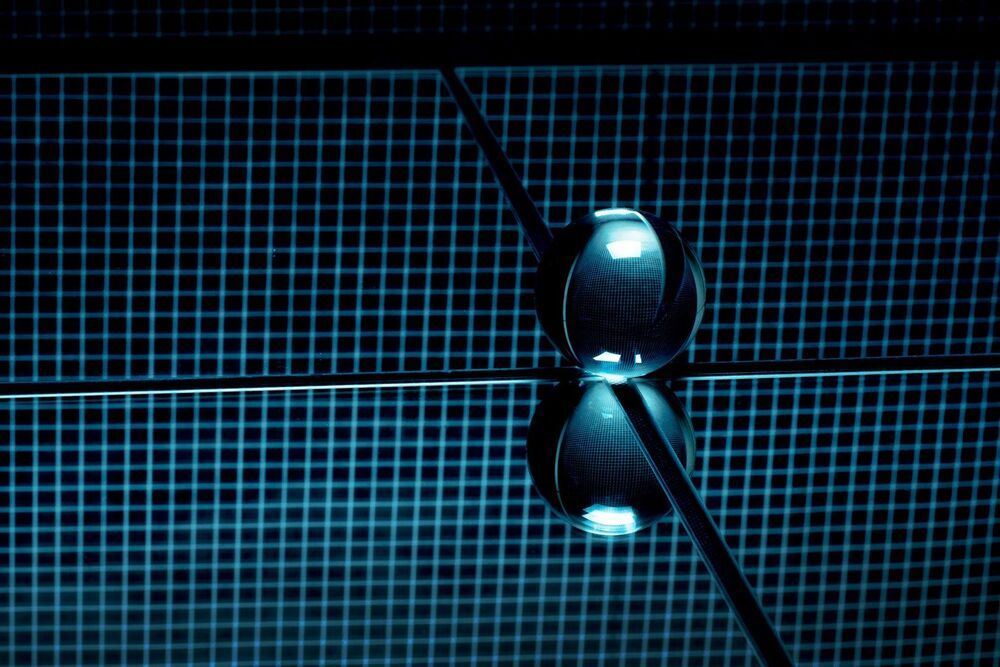

Last month, Indiana’s Department of Transport (INDOT) announced a collaboration with Purdue University and German company Magment to test out whether cement with embedded magnetized particles could provide an affordable road-charging solution.

Most wireless vehicle charging technologies rely on a process known as inductive charging, where electricity pumped into a wire coil creates a magnetic field that can induce an electric current in any other nearby wire coil. The charging coils are installed at regular intervals under the road, and cars are fitted with a receiver coil that picks up the charge.

But installing thousands of miles of copper under the road is obviously fairly costly. Magment’s solution is to instead embed standard concrete with recycled ferrite particles, which are also able to generate a magnetic field but are considerably cheaper. The company claims its product can achieve transmission efficiency of up to 95 percent and can be built at “standard road-building installation costs.”

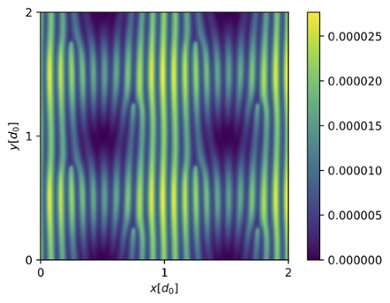

A new way to probe exotic matter aids the study of atomic and particle physics.

Physicists have created a new way to observe details about the structure and composition of materials that improves upon previous methods. Conventional spectroscopy changes the frequency of light shining on a sample over time to reveal details about them. The new technique, Rabi-oscillation spectroscopy, does not need to explore a wide frequency range so can operate much more quickly. This method could be used to interrogate our best theories of matter in order to form a better understanding of the material universe.

Though we cannot see them with the naked eye, we are all familiar with the atoms that make up everything we see around us. Collections of positive protons, neutral neutrons and negative electrons give rise to all the matter we interact with. However, there are some more exotic forms of matter, including exotic atoms, which are not made from these three basic components. Muonium, for example, is like hydrogen, which typically has one electron in orbit around one proton, but has a positively charged muon particle in place of the proton.

Majoranas particles found.

Majorana particles have been getting bad publicity: a claimed discovery in ultracold nanowires had to be retracted. Now Leiden physicists open up a new door to detecting Majoranas in a different experimental system, the Fu-Kane heterostructure, they announce in Physical Review Letters.

Majorana particles are quasiparticles: collective movements of particles (electrons in this case) which behave as single particles. If detected in real life, they could be used to build stable quantum computers.

“Majoranas are quantum mechanical superpositions,” explains Gal Lemut. This superposition, a special kind of combination, comprises an electron and a hole (a place in a crystal where an electron is missing.

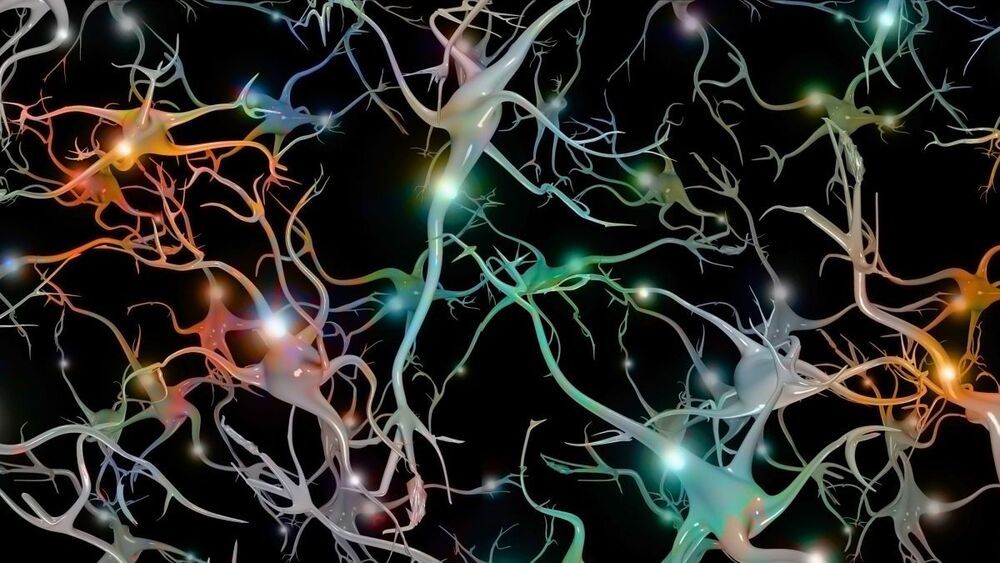

Scientists have created key parts of synthetic brain cells that can hold cellular “memories” for milliseconds. The achievement could one day lead to computers that work like the human brain.

These parts, which were used to model an artificial brain cell, use charged particles called ions to produce an electrical signal, in the same way that information gets transferred between neurons in your brain.

Circa 2020

The basic idea behind all nuclear power plants is the same: Convert the heat created by nuclear fission into electricity. There are several ways to do this, but in each case it involves a delicate balancing act between safety and efficiency. A nuclear reactor works best when the core is really hot, but if it gets too hot it will cause a meltdown and the environment will get poisoned and people may die and it will take billions of dollars to clean up the mess.

The last time this happened was less than a decade ago, when a massive earthquake followed by a series of tsunamis caused a meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant in Japan. But a new generation of reactors coming online in the next few years aims to make these kinds of disasters a thing of the past. Not only will these reactors be smaller and more efficient than current nuclear power plants, but their designers claim they’ll be virtually meltdown-proof. Their secret? Millions of submillimeter-size grains of uranium individually wrapped in protective shells. It’s called triso fuel, and it’s like a radioactive gobstopper.

Triso— short for “tristructural isotropic”—fuel is made from a mixture of low enriched uranium and oxygen, and it is surrounded by three alternating layers of graphite and a ceramic called silicon carbide. Each particle is smaller than a poppy seed, but its layered shell can protect the uranium inside from melting under even the most extreme conditions that could occur in a reactor.

Physicists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have linked together, or “entangled,” the mechanical motion and electronic properties of a tiny blue crystal, giving it a quantum edge in measuring electric fields with record sensitivity that may enhance understanding of the universe.

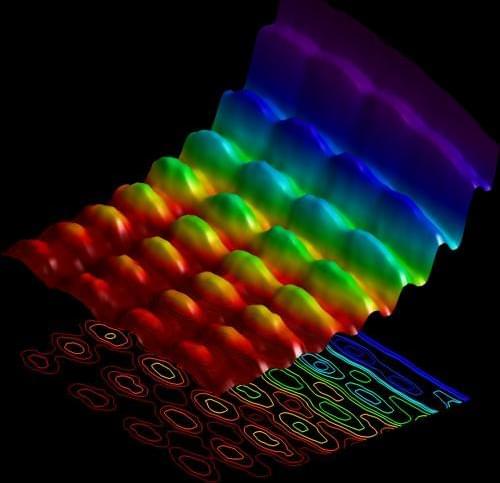

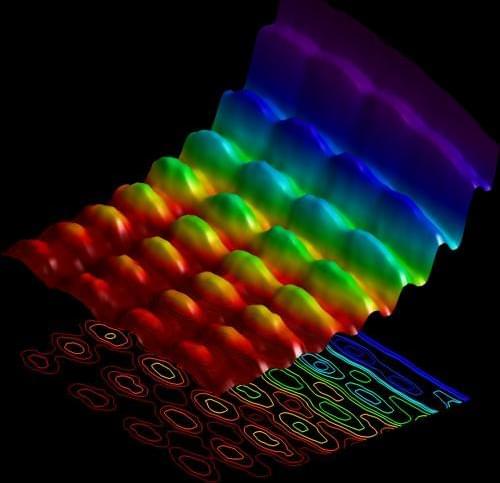

The quantum sensor consists of 150 beryllium ions (electrically charged atoms) confined in a magnetic field, so they self-arrange into a flat 2D crystal just 200 millionths of a meter in diameter. Quantum sensors such as this have the potential to detect signals from dark matter — a mysterious substance that might turn out to be, among other theories, subatomic particles that interact with normal matter through a weak electromagnetic field. The presence of dark matter could cause the crystal to wiggle in telltale ways, revealed by collective changes among the crystal’s ions in one of their electronic properties, known as spin.

As described in the August 6, 2021, issue of Science, researchers can measure the vibrational excitation of the crystal — the flat plane moving up and down like the head of a drum — by monitoring changes in the collective spin. Measuring the spin indicates the extent of the vibrational excitation, referred to as displacement.