It’s not often that messing around in the lab has produced a fundamental breakthrough, à la Michael Faraday with his magnets and prisms. Even more uncommon is the discovery of the same thing by two research teams at the same time: Newton and Leibniz come to mind. But every so often, even the rarest of events does happen. The summer of 2021 has been a banner season for condensed-matter physics. Three separate teams of researchers have created a crystal made entirely of electrons — and one of them actually did it by accident.

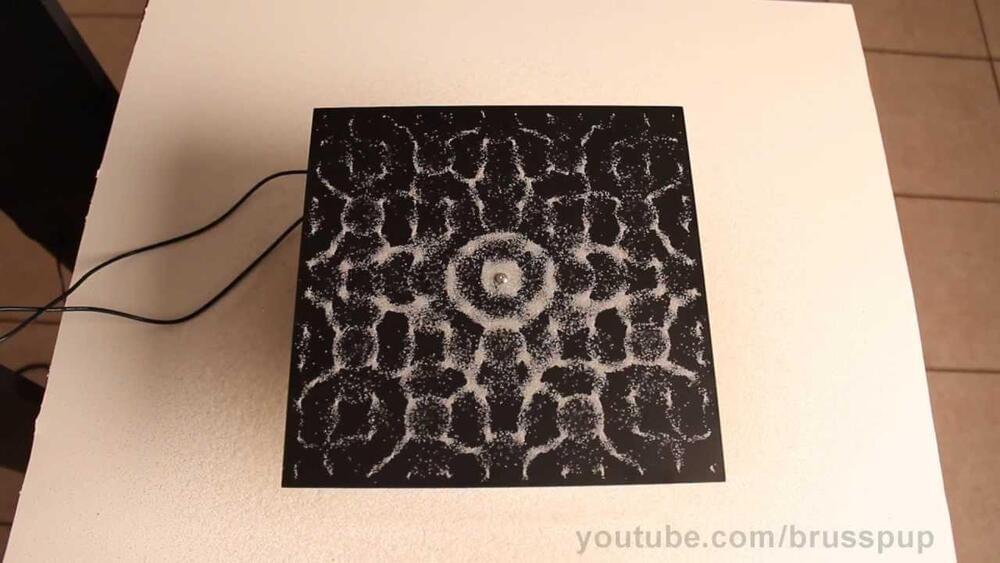

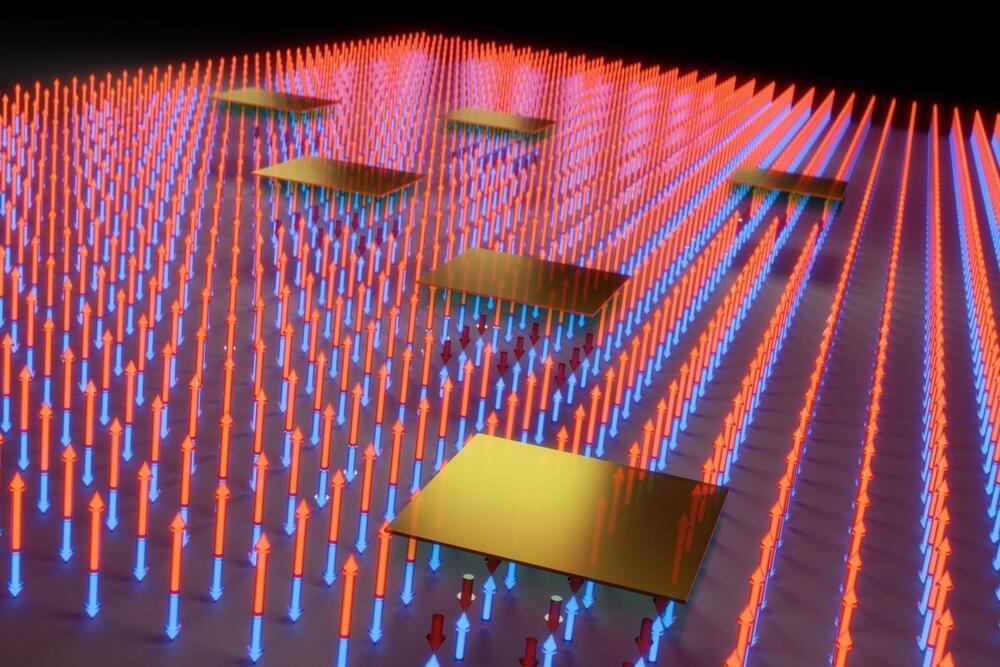

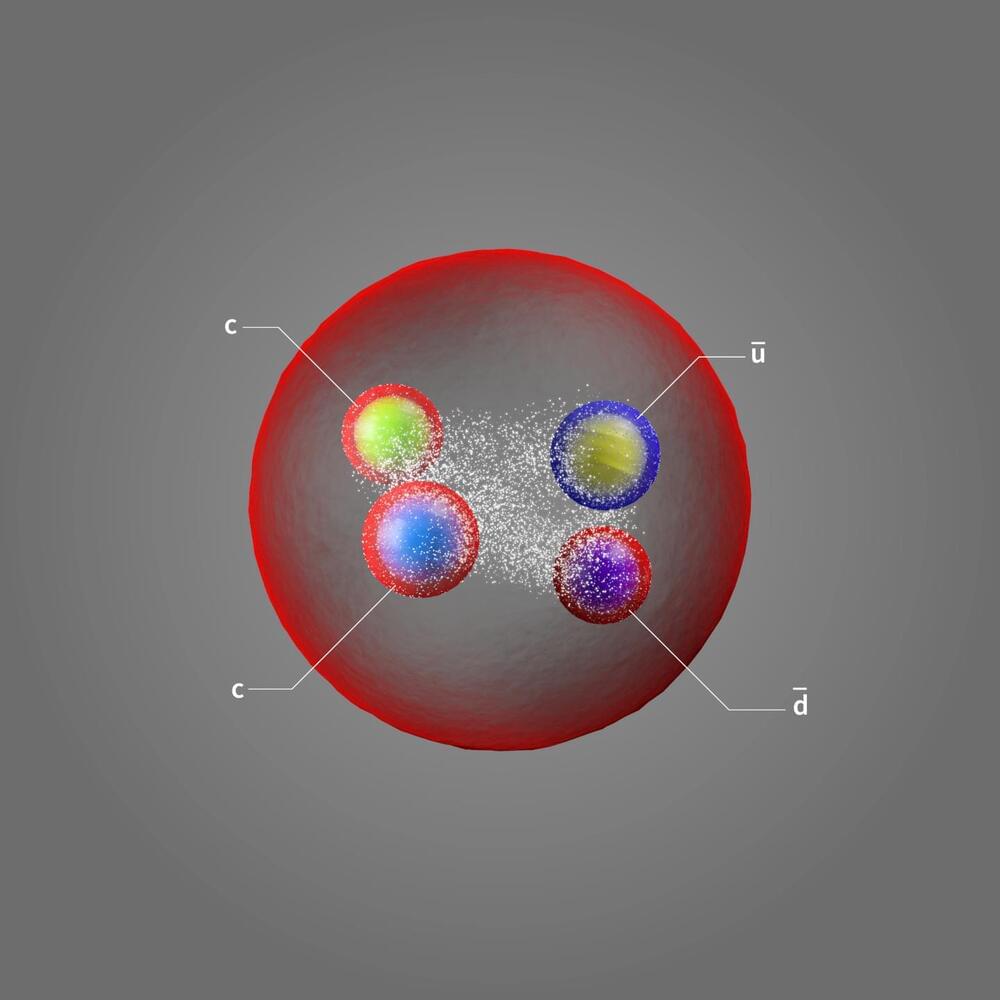

The researchers were working with single-atom-thick semiconductors, cooled to ultra-low temperatures. One team, led by Hongkun Park along with Eugene Demler, both of Harvard, discovered that when very specific numbers of electrons were present in the layers of these slivers of semiconductor, the electrons stopped in their tracks and stood “mysteriously still.” Eventually colleagues recalled an old idea having to do with Wigner crystals, which were one of those things that exist on paper and in theory but had never been verified in life. Wigner had calculated that because of mutual electrostatic repulsion, electrons in a monolayer would assume a tri-grid pattern.

Park and Demler’s group was not alone in its travails. “A group of theoretical physicists led by Eugene Demler of Harvard University, who is moving to ETH [ETH Zurich, in Switzerland] this year, had calculated theoretically how that effect should show up in the observed excitation frequencies of the excitons – and that’s exactly what we observed in the lab,” said Ataç Imamoğlu, himself from ETH. Imamoğlu’s group used the same technique to document the formation of a Wigner crystal.