A new chapter in physics is here, says a team that hunted for a key building block of the Universe.

Topology in optics and photonics has been a hot topic since 1,890 where singularities in electromagnetic fields have been considered. The recent award of the Nobel prize for topology developments in condensed matter physics has led to renewed surge in topology in optics with most recent developments in implementing condensed matter particle-like topological structures in photonics. Recently, topological photonics, especially the topological electromagnetic pulses, hold promise for nontrivial wave-matter interactions and provide additional degrees of freedom for information and energy transfer. However, to date the topology of ultrafast transient electromagnetic pulses had been largely unexplored.

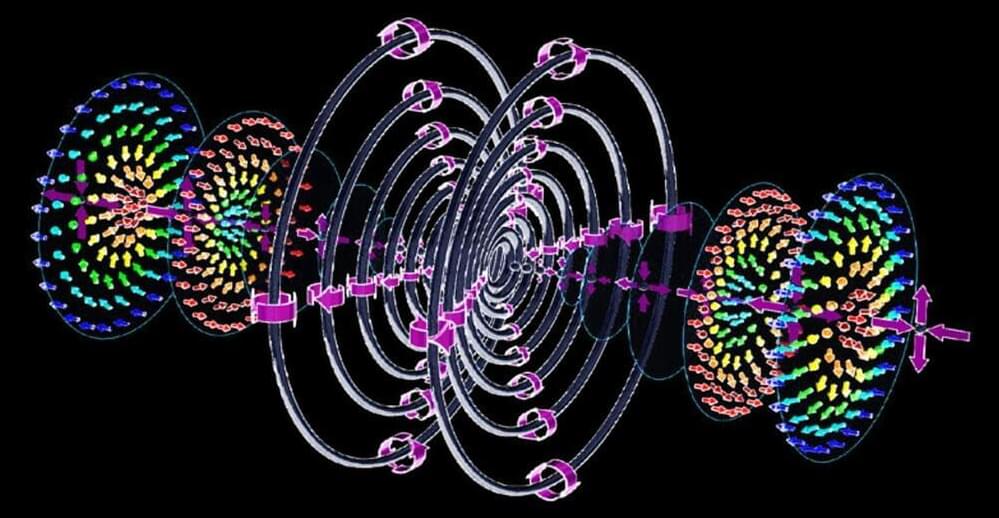

In their paper published in the journal Nature Communications, physicists in the UK and Singapore report a new family of electromagnetic pulses, the exact solutions of Maxwell’s equation with toroidal topology, in which topological complexity can be continuously controlled, namely supertoroidal topology. The electromagnetic fields in such supertoroidal pulses have skyrmionic structures as they propagate in free space with the speed of light.

Skyrmions, sophisticated topological particles originally proposed as a unified model of the nucleon by Tony Skyrme in 1,962 behave like nanoscale magnetic vortices with spectacular textures. They have been widely studied in many condensed matter systems, including chiral magnets and liquid crystals, as nontrivial excitations showing great importance for information storing and transferring. If skyrmions can fly, open up infinite possibilities for the next generation of informatics revolution.

The infamous twin paradox sends the astronaut Alice on a blazing-fast space voyage. When she returns to reunite with her twin, Bob, she finds that he has aged much faster than she has. It’s a well-known but perplexing result: Time slows if you’re moving fast.

Gravity does the same thing. Earth — or any massive body — warps space-time in a way that slows time, according to Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. If Alice lived her life at sea level and Bob at the top of Everest, where Earth’s gravitational pull is slightly weaker, he would again age faster. The difference on Earth is modest but real — it’s been measured by putting atomic clocks on mountaintops and valley floors and measuring the difference between the two.

Physicists have now managed to measure this difference to the millimeter. In a paper posted earlier this month to the scientific preprint server arxiv.org, researchers from the lab of Jun Ye, a physicist at JILA in Boulder, Colorado, measured the difference in the flow of time between the top and the bottom of a millimeter-tall cloud of atoms.

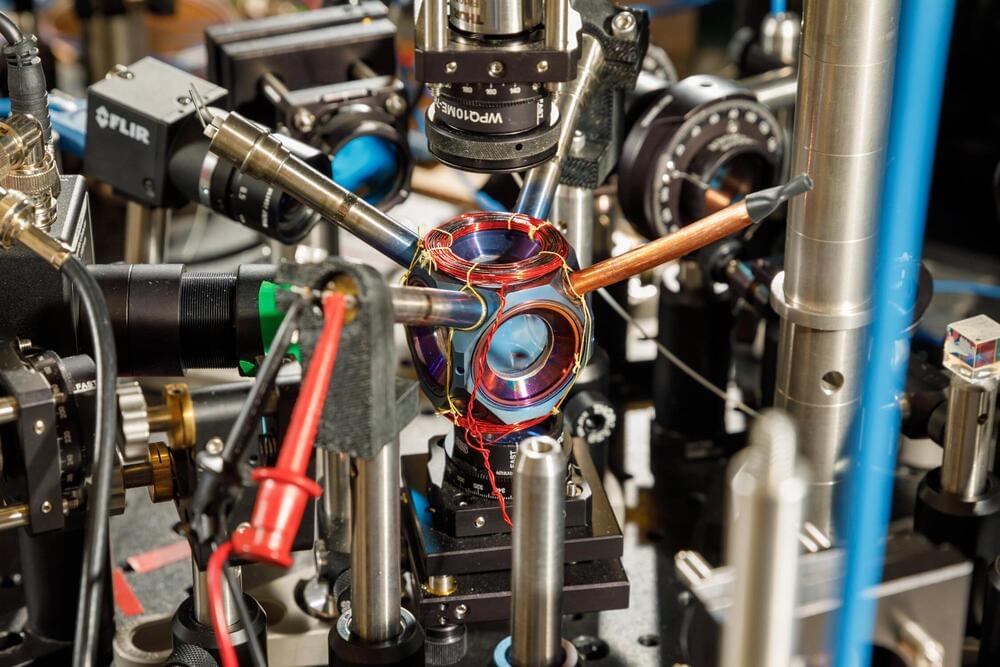

Don’t let the titanium metal walls or the sapphire windows fool you. It’s what’s on the inside of this small, curious device that could someday kick off a new era of navigation.

For over a year, the avocado-sized vacuum chamber has contained a cloud of atoms at the right conditions for precise navigational measurements. It is the first device that is small, energy-efficient and reliable enough to potentially move quantum sensors—sensors that use quantum mechanics to outperform conventional technologies—from the lab into commercial use, said Sandia National Laboratories scientist Peter Schwindt.

Sandia developed the chamber as a core technology for future navigation systems that don’t rely on GPS satellites, he said. It was described earlier this year in the journal AVS Quantum Science.

Estimate measures information encoded in particles, opens door to practical experiments.

Researchers have long suspected a connection between information and the physical universe, with various paradoxes and thought experiments used to explore how or why information could be encoded in physical matter. The digital age propelled this field of study, suggesting that solving these research questions could have tangible applications across multiple branches of physics and computing.

In AIP Advances, from AIP Publishing, a University of Portsmouth researcher attempts to shed light on exactly how much of this information is out there and presents a numerical estimate for the amount of encoded information in all the visible matter in the universe — approximately 6 times 10 to the power of 80 bits of information. While not the first estimate of its kind, this study’s approach relies on information theory.

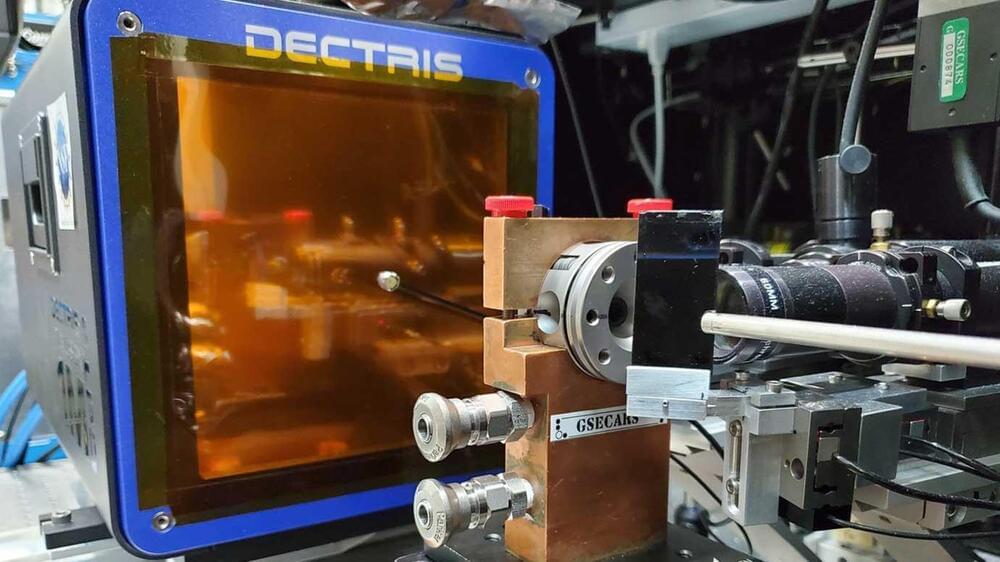

Scientists at the University of Chicago say that they’ve successfully created a “strange” new state of matter in the laboratory called “superionic ice” — and that the stuff might already exist inside planets in our solar system.

“It was a surprise — everyone thought this phase wouldn’t appear until you are at much higher pressures than where we first find it,” co-author and University of Chicago researcher Vitali Prakapenka said in a press blurb. “But we were able to very accurately map the properties of this new ice, which constitutes a new phase of matter, thanks to several powerful tools.”

Prakapenka’s team used a particle acclerator to fire electons between two pieces of diamond, creating unfathomable pressures of 20 gigapascals in a sample of water and causing it to form an entirely new structure that reverted when they relieved the pressure.

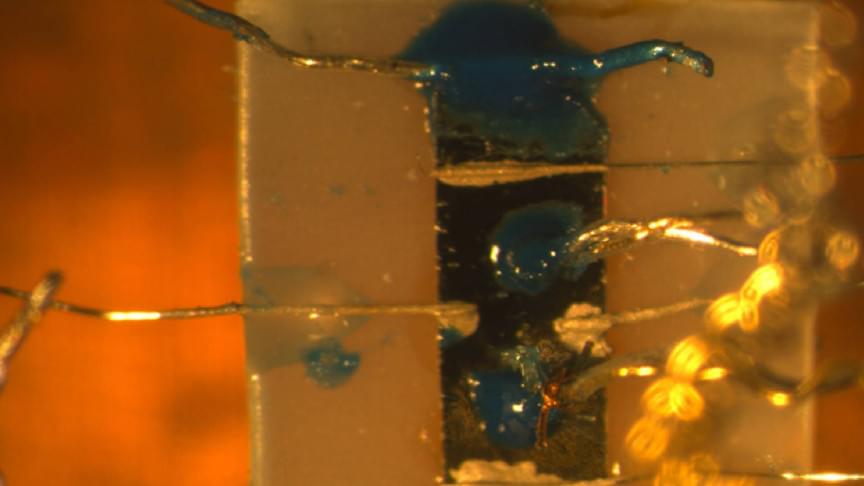

The iron-based superconductor material, Ba1−xKxFe2As2. Vadim Grinenko, Federico Caglieris/KTH Royal Institute of Technology

Twenty years ago, scientists first predicted electron quadruplets. Now, KTH Professor Egor Babaev, with the aid of international collaborators, has revealed evidence of fermion quadrupling in a series of experimental measurements on the iron-based material, Ba 1−x Kx Fe 2 As 2.

This is the first-ever experimental evidence of this quadrupling effect and the mechanism by which this state of matter occurs.

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) sparked worldwide excitement in March as particle physicists reported tantalising evidence for new physics — potentially a new force of nature. Now, our new result, yet to be peer reviewed, from Cern’s gargantuan particle collider seems to be adding further support to the idea.

Our current best theory of particles and forces is known as the standard model, which describes everything we know about the physical stuff that makes up the world around us with unerring accuracy. The standard model is without doubt the most successful scientific theory ever written down and yet at the same time we know it must be incomplete.

Famously, it describes only three of the four fundamental forces – the electromagnetic force and strong and weak forces, leaving out gravity. It has no explanation for the dark matter that astronomy tells us dominates the universe, and cannot explain how matter survived during the big bang. Most physicists are therefore confident that there must be more cosmic ingredients yet to be discovered, and studying a variety of fundamental particles known as beauty quarks is a particularly promising way to get hints of what else might be out there.

Most of us control light all the time without even thinking about it, usually in mundane ways: we don a pair of sunglasses and put on sunscreen, and close—or open—our window blinds.

But the control of light can also come in high-tech forms. The screen of the computer, tablet, or phone on which you are reading this is one example. Another is telecommunications, which controls light to create signals that carry data along fiber-optic cables.

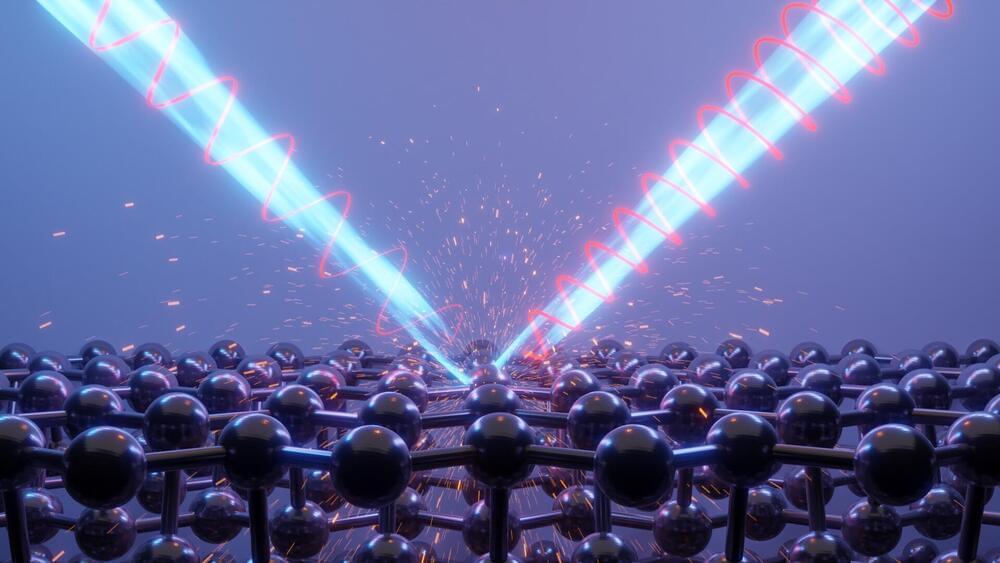

Scientists also use high-tech methods to control light in the laboratory, and now, thanks to a new breakthrough that uses a specialized material only three atoms thick, they can control light more precisely than ever before.