Get your SPECIAL OFFER for MagellanTV here: https://try.magellantv.com/arvinash — It’s an exclusive offer for our viewers! Start your free trial today. MagellanTV is a new kind of streaming service run by filmmakers with 3,000+ documentaries! Check out our personal recommendation and MagellanTV’s exclusive playlists: https://www.magellantv.com/genres/science-and-tech.

Arguments for fine tuning: Physics has many constants like the charge of the electron, the gravitational constant, Planck’s constant. If any of their values were different, our universe, as we know it, would not be the same, and life would probably not exist.

0:00 — Defining fine tuning.

2:20 — Gravitational constant.

3:59 — Electromagnetic Force.

5:02 — Strong force.

6:13 — Weak force.

7:51 — Philosophical Arguments against fine tuning.

9:36 — Scientific arguments against fine tuning.

11:59 — Sentient puddle.

13:29 — Does fine tuning need an agent.

15:14 — Louse on the tail a lion.

Some say that it could not have occurred by chance, that there must be some agent, like a god that set up the constants to enable life.

Let’s just look at the constants associated with the different forces. Gravity: If the gravitational constant was too small, gravity would be too weak, and planets wouldn’t form. If it was too large, then stars like the sun would burn up too fast.

Electromagnetism: The electromagnetic force is responsible for the distance at which electrons orbits in atoms. If the force was weaker, the atomic size would increase because electrons would be further away from the nucleus. This could impact chemistry, as it would change the strength of chemical bonds.

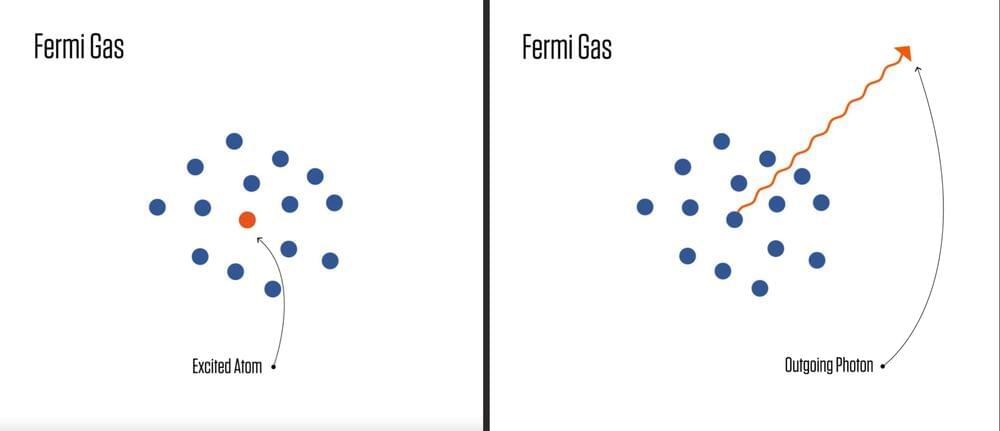

A higher constant would lead to cooler stars and a lower constant would lead to hotter stars. If the constant was bigger, atoms larger than hydrogen atoms could not form and stars may never ignite, because protons may not have been able to overcome the coulomb barrier to fuse in the first place.

Strong force: If the strong coupling constant were lower, then you wouldn’t have stable heavy atoms as it would not be enough to overcome proton-proton repulsion. If the strong nuclear force was only 1% weaker for example, atoms crucial for life like oxygen, carbon and nitrogen may not form in sufficient quantities.