Start your Audible trial today: http://www.audible.com/spacetime.

Hello from the other side. In this episode find out how quanta can can move through solid objects.

Get your own Space Time tshirt at http://bit.ly/1QlzoBi.

Tweet at us! @pbsspacetime.

Facebook: facebook.com/pbsspacetime.

Email us! pbsspacetime [at] gmail [dot] com.

Comment on Reddit: http://www.reddit.com/r/pbsspacetime.

Support us on Patreon! http://www.patreon.com/pbsspacetime.

Help translate our videos! http://www.youtube.com/timedtext_cs_panel?tab=2&c=UC7_gcs09iThXybpVgjHZ_7g.

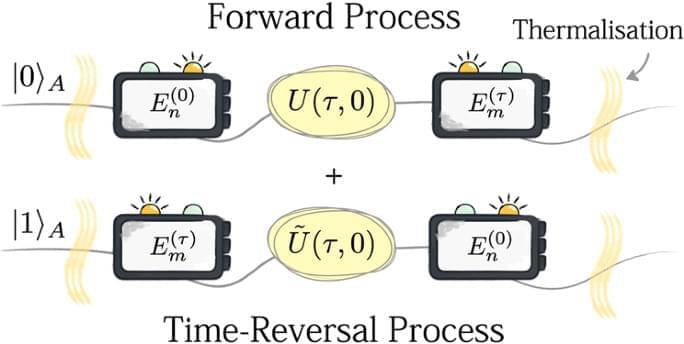

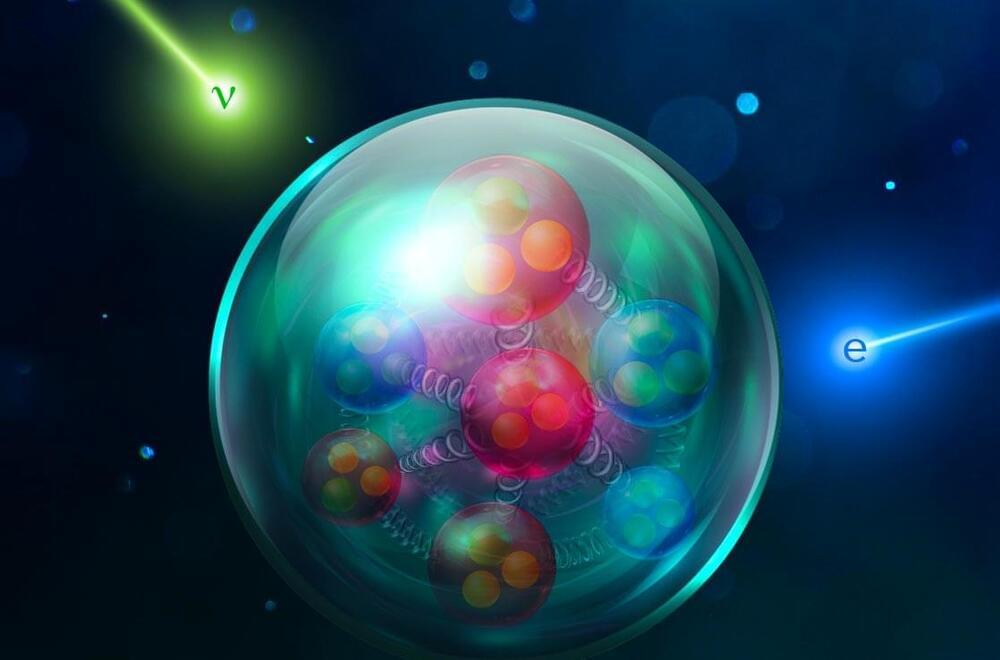

Where are you right now? Until you interact with another particle you could be any number of places within a wave of probabilities. This is only one way that quantum mechanics challenges our perception of reality. Matt dives into these counter-intuitive ideas and explains the bizarre phenomenon known as quantum tunneling in this episode of Space Time.

Written and hosted by Matt O’Dowd.