:00000

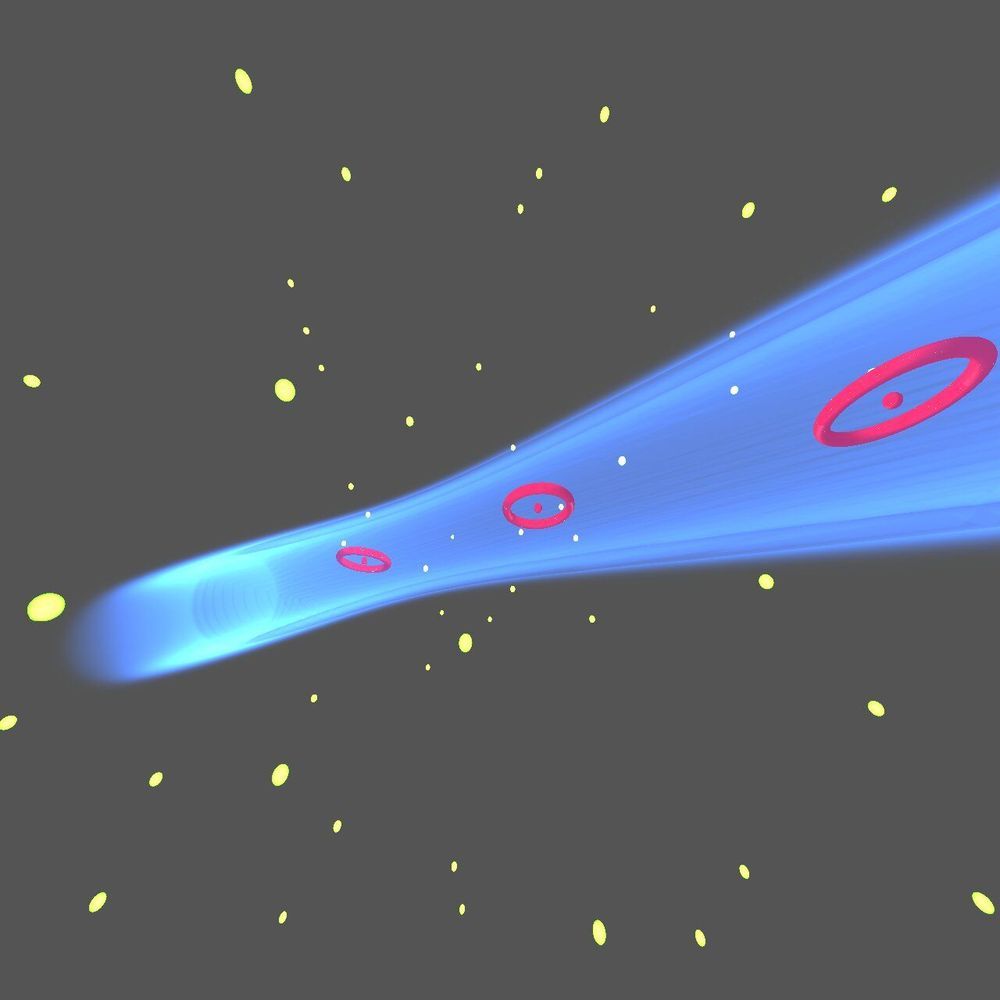

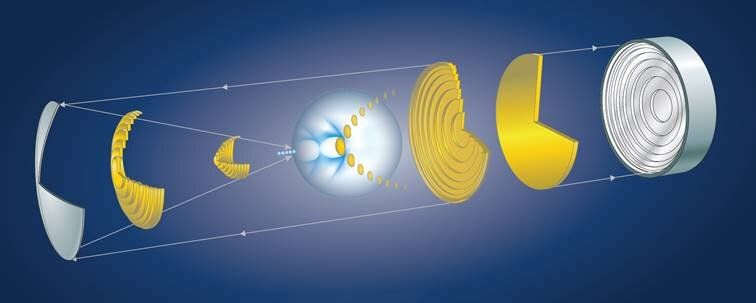

In novel concepts of magnetic data storage, it is intended to send small magnetic bits back and forth in a chip structure, store them densely packed and read them out later. The magnetic stray field generates problems when trying to generate particularly tiny bits. Now, researchers at the Max Born Institute (MBI), the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and DESY were able to put an “invisibility cloak” over the magnetic structures. In this fashion, the magnetic stray field can be reduced in a fashion allowing for small yet mobile bits. The results were published in Nature Nanotechnology.

For physicists, magnetism is intimately coupled to rotating motion of electrons in atoms. Orbiting around the atomic nucleus as well as around their own axis, electrons generate the magnetic moment of the atom. The magnetic stray field associated with that magnetic moment is the property we know from e.g. a bar magnet we use to fix notes on pinboard. It is also the magnetic stray field that is used to read the information from a magnetic hard disk drive. In today’s hard disks, a single magnetic bit has a size of about 15 x 45 nanometer, about 1,000,000,000,000 of those would fit on a stamp.

One vision for a novel concept to store data magnetically is to send the magnetic bits back and forth in a memory chip via current pulses, in order to store them at a suitable place in the chip and retrieve them later. Here, the magnetic stray field is a bit of a curse, as it prevents that the bits can be made smaller for even denser packing of the information. On the other hand, the magnetic moment underlying the stray field is required to be able to move the structures around.