- The small, spherical Tokamak ST40 reactor is on track to reach its next goal of hitting the 15,000,000 °C (27,000,000 °F) mark this autumn.

- When it does, we will be one step closer to achieving fusion power on a commercial scale.

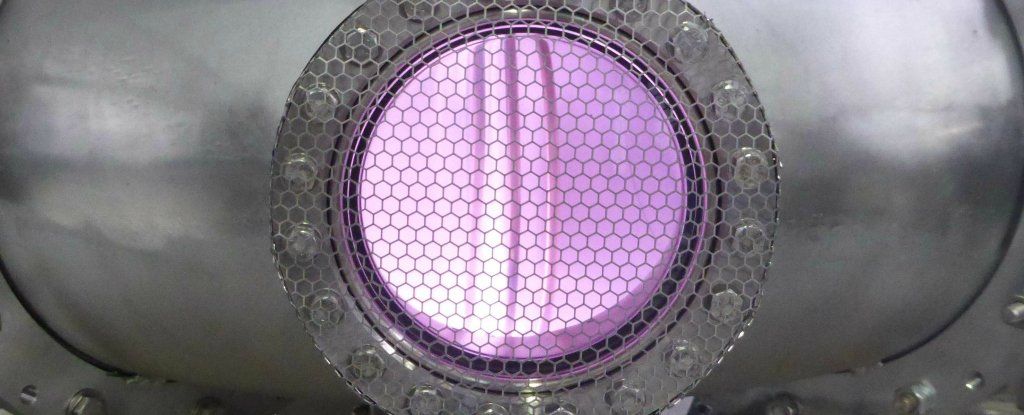

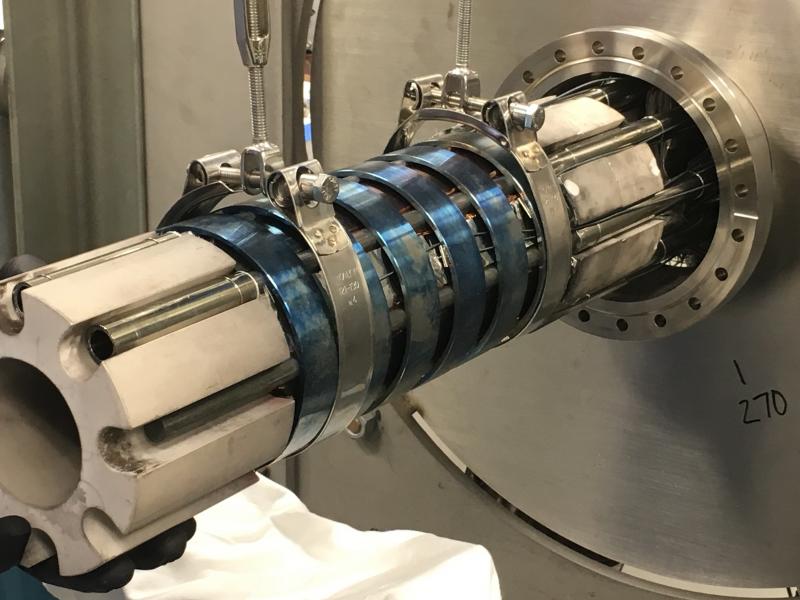

Earlier this month the newest fusion reactor in the U.K., Tokamak Energy’s ST40, achieved first plasma. This milestone event on the road to fusion energy signals the viability of the company’s overall timetable. The more immediate aim for the ST40 is to achieve a temperature of 15,000,000 °C (27,000,000 °F), as hot as the center of the sun — this should happen in autumn of 2017 based on the progress thus far.