My sociology of knowledge students read Yuval Harari’s bestselling first book, Sapiens, to think about the right frame of reference for understanding the overall trajectory of the human condition. Homo Deus follows the example of Sapiens, using contemporary events to launch into what nowadays is called ‘big history’ but has been also called ‘deep history’ and ‘long history’. Whatever you call it, the orientation sees the human condition as subject to multiple overlapping rhythms of change which generate the sorts of ‘events’ that are the stuff of history lessons. But Harari’s history is nothing like the version you half remember from school.

In school historical events were explained in terms more or less recognizable to the agents involved. In contrast, Harari reaches for accounts that scientifically update the idea of ‘perennial philosophy’. Aldous Huxley popularized this phrase in his quest to seek common patterns of thought in the great world religions which could be leveraged as a global ethic in the aftermath of the Second World War. Harari similarly leverages bits of genetics, ecology, neuroscience and cognitive science to advance a broadly evolutionary narrative. But unlike Darwin’s version, Harari’s points towards the incipient apotheosis of our species; hence, the book’s title.

This invariably means that events are treated as symptoms if not omens of the shape of things to come. Harari’s central thesis is that whereas in the past we cowered in the face of impersonal natural forces beyond our control, nowadays our biggest enemy is the one that faces us in the mirror, which may or may not be able within our control. Thus, the sort of deity into which we are evolving is one whose superhuman powers may well result in self-destruction. Harari’s attitude towards this prospect is one of slightly awestruck bemusement.

Here Harari equivocates where his predecessors dared to distinguish. Writing with the bracing clarity afforded by the Existentialist horizons of the Cold War, cybernetics founder Norbert Wiener declared that humanity’s survival depends on knowing whether what we don’t know is actually trying to hurt us. If so, then any apparent advance in knowledge will always be illusory. As for Harari, he does not seem to see humanity in some never-ending diabolical chess match against an implacable foe, as in The Seventh Seal. Instead he takes refuge in the so-called law of unintended consequences. So while the shape of our ignorance does indeed shift as our knowledge advances, it does so in ways that keep Harari at a comfortable distance from passing judgement on our long term prognosis.

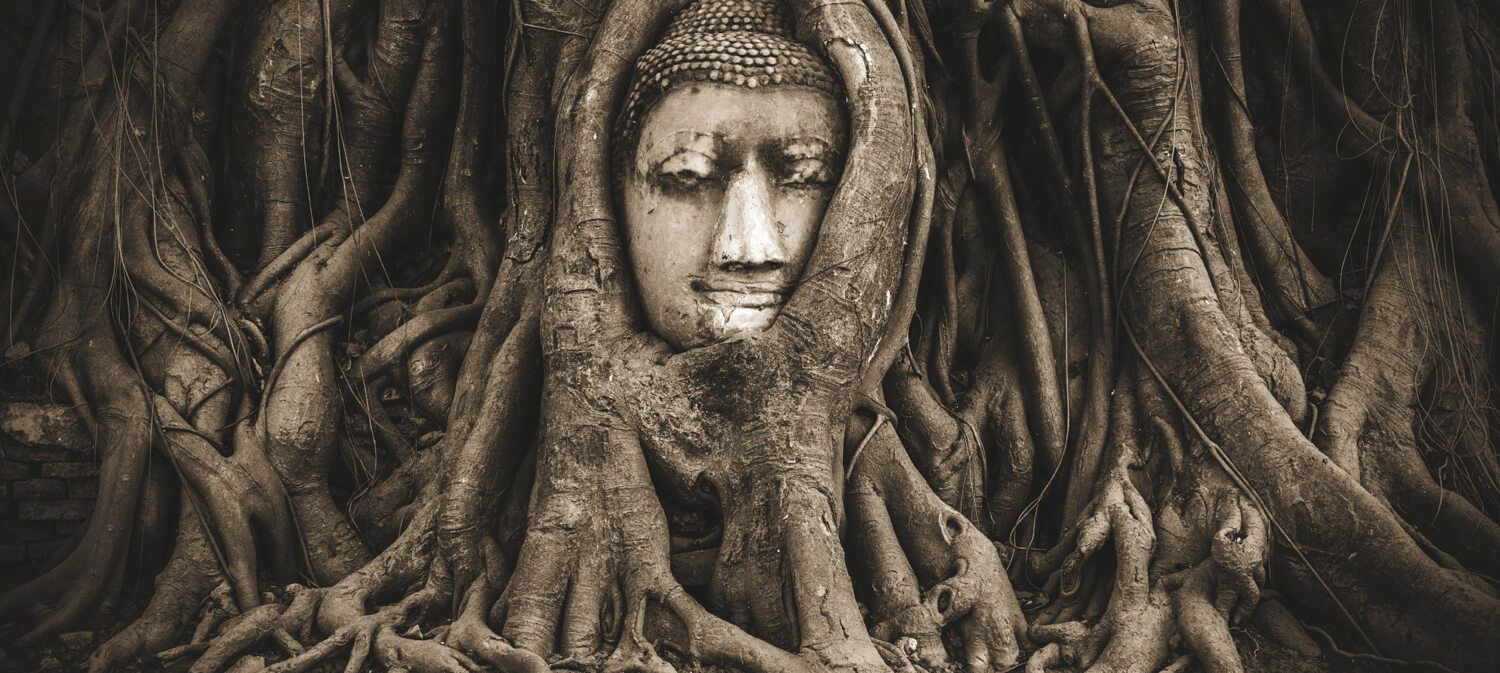

This semi-detachment makes Homo Deus a suave but perhaps not deep read of the human condition. Consider his choice of religious precedents to illustrate that we may be approaching divinity, a thesis with which I am broadly sympathetic. Instead of the Abrahamic God, Harari tends towards the ancient Greek and Hindu deities, who enjoy both superhuman powers and all too human foibles. The implication is that to enhance the one is by no means to diminish the other. If anything, it may simply make the overall result worse than had both our intellects and our passions been weaker. Such an observation, a familiar pretext for comedy, wears well with those who are inclined to read a book like this only once.

One figure who is conspicuous by his absence from Harari’s theology is Faust, the legendary rogue Christian scholar who epitomized the version of Homo Deus at play a hundred years ago in Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West. What distinguishes Faustian failings from those of the Greek and Hindu deities is that Faust’s result from his being neither as clever nor as loving as he thought. The theology at work is transcendental, perhaps even Platonic.

In such a world, Harari’s ironic thesis that future humans might possess virtually perfect intellects yet also retain quite undisciplined appetites is a non-starter. If anything, Faust’s undisciplined appetites point to a fundamental intellectual deficiency that prevents him from exercising a ‘rational will’, which is the mark of a truly supreme being. Faust’s sense of his own superiority simply leads him down a path of ever more frustrated and destructive desire. Only the one true God can put him out of his misery in the end.

In contrast, if there is ‘one true God’ in Harari’s theology, it goes by the name of ‘Efficiency’ and its religion is called ‘Dataism’. Efficiency is familiar as the dimension along which technological progress is made. It amounts to discovering how to do more with less. To recall Marshall McLuhan, the ‘less’ is the ‘medium’ and the ‘more’ is the ‘message’. However, the metaphysics of efficiency matters. Are we talking about spending less money, less time and/or less energy?

It is telling that the sort of efficiency which most animates Harari’s account is the conversion of brain power to computer power. To be sure, computers can outperform humans on an increasing range of specialised tasks. Moreover, computers are getting better at integrating the operations of other technologies, each of which also typically replaces one or more human functions. The result is the so-called Internet of Things. But does this mean that the brain is on the verge of becoming redundant?

Those who say yes, most notably the ‘Singularitarians’ whose spiritual home is Silicon Valley, want to translate the brain’s software into a silicon base that will enable it to survive and expand indefinitely in a cosmic Internet of Things. Let’s suppose that such a translation becomes feasible. The energy requirements of such scaled up silicon platforms might still be prohibitive. For all its liabilities and mysteries, the brain remains the most energy efficient medium for encoding and executing intelligence. Indeed, forward facing ecologists might consider investing in a high-tech agronomy dedicated to cultivating neurons to function as organic computers – ‘Stem Cell 2.0’, if you will.

However, Harari does not see this possible future because he remains captive to Silicon Valley’s version of determinism, which prescribes a migration from carbon to silicon for anything worth preserving indefinitely. It is against this backdrop that he flirts with the idea that a computer-based ‘superintelligence’ might eventually find humans surplus to requirements in a rationally organized world. Like other Singularitarians, Harari approaches the matter in the style of a 1950s B-movie fan who sees the normative universe divided between ‘us’ (the humans) and ‘them’ (the non-humans).

The bravest face to put on this intuition is that computers will transition to superintelligence so soon – ‘exponentially’ as the faithful say — that ‘us vs. them’ becomes an operative organizing principle. More likely and messier for Harari is that this process will be dragged out. And during that time Homo sapiens will divide between those who identify with their emerging machine overlords, who are entitled to human-like rights, and those who cling to the new acceptable face of racism, a ‘carbonist’ ideology which would privilege organic life above any silicon-based translations or hybridizations. Maybe Harari will live long enough to write a sequel to Homo Deus to explain how this battle might pan out.

NOTE ON PUBLICATION: Homo Deus is published in September 2016 by Harvil Secker, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Fuller would like to thank The Literary Review for originally commissioning this review. It will appear in a subsequent edition of the magazine and is published here with permission.