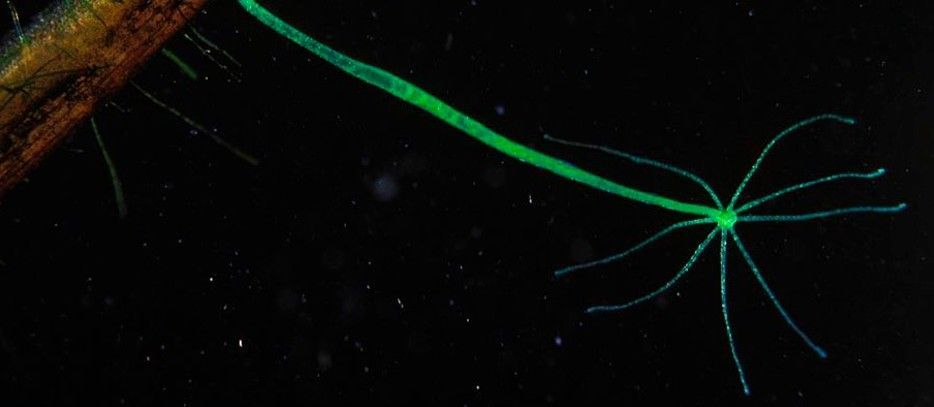

Our body’s ability to detect disease, foreign material, and the location of food sources and toxins is all determined by a cocktail of chemicals that surround our cells, as well as our cells’ ability to ‘read’ these chemicals. Cells are highly sensitive. In fact, our immune system can be triggered by the presence of just one foreign molecule or ion. Yet researchers don’t know how cells achieve this level of sensitivity.

Now, scientists at the Biological Physics Theory Unit at Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) and collaborators at City University of New York have created a simple model that is providing some answers. They have used this model to determine which techniques a cell might employ to increase its sensitivity in different circumstances, shedding light on how the biochemical networks in our bodies operate.

“This model takes a complex biological system and abstracts it into a simple, understandable mathematical framework,” said Dr. Vudtiwat Ngampruetikorn, former postdoctoral researcher at OIST and the first author of the research paper, which was published in Nature Communications. “We can use it to tease apart how cells might choose to spend their energy budget, depending on the world around them and other cells they might be talking to.”

By bringing a quantitative toolkit to this biological question, the scientists found that they had a different perspective to the biologists. “The two disciplines are complimentary to one another,” said Professor Greg Stephens, who runs the unit. “Biologists tend to focus on one area and delve deeply into the details, whereas physicists simplify and look for patterns across entire systems. It’s important that we work closely together to make sure that our quantitative models aren’t too abstract and include the important details.”

On their computers, the scientists created the model that represented a cell. The cell had two sensors (or information processing units), which responded to the environment outside the cell. The sensors could either be bound to a molecule or ion from the outside, or unbound. When the number of molecules or ions in chemical cocktail outside the cell changed, the sensors would respond and, depending on these changes, either bind to a new molecule or ion, or unbind. This allowed the cell to gain information about the outside world and thus allowed the scientists to measure what could impact its sensitivity.

“Once we had the model, we could test all sorts of questions,” said Dr. Ngampruetikorn, “For example, is the cell more sensitive if we allow it to consume more energy? Or if we allow the two sensors to cooperate? How does the cell’s prior experiences influence its sensitivity?”

The scientists looked at whether allowing the cell to consume energy and allowing the two sensors to interact helped the cell achieve a higher level of sensitivity. They also decided to vary two other components to see if this had an impact—the level of noise, which refers to the amount of uncertainty or unnecessary information in the chemical cocktail, and the signal prior, which refers to the cell’s acquired knowledge, gained from past experiences.

Previous research had found that energy consumption and sensor interactions were important for cell sensitivity, but this research found that that was not always true. In some situations—such as if the chemical cocktail had a low level of noise and the correlations between different chemicals are high—the scientists found that allowing the cell to consume energy and the sensors to interact did help it achieve a higher level of sensitivity. However, in other situations—such as if there was a higher level of noise—this was not the case.

“It’s like tuning into a radio,” explained Professor Stephens. “If there’s too much static (or noise), it doesn’t do any good to turn up the radio (or, in this case, amplify the signal with energy and interactions).”

Despite this, Dr. Ngampruetikorn explained, energy consumption and sensor interactions do remain important mechanisms in many situations. “It would be interesting to continue to use this model to determine exactly how energy consumption can influence a cell’s sensitivity,” he said. “And in what situations it’s most valuable.”

Although the scientists decided to look specifically at how cells respond to their surroundings, they stressed that the general framework of their model could be used to shed light on sensing strategies across the biological world. Professor Stephens explained that whilst there’s a huge amount of effort going in to characterizing isolated, individual systems, there’s considerably less work looking for common principles. “If we can find these principles, then it could renew our understanding of how living systems function, from cell communication and the brain, to animal behavior and social interactions.”

Scientists create model to measure how cells sense their surroundings.