This amazing research out of MIT could have big implications for gadgets and fashion.

This amazing research out of MIT could have big implications for gadgets and fashion.

Tokyo (AFP)

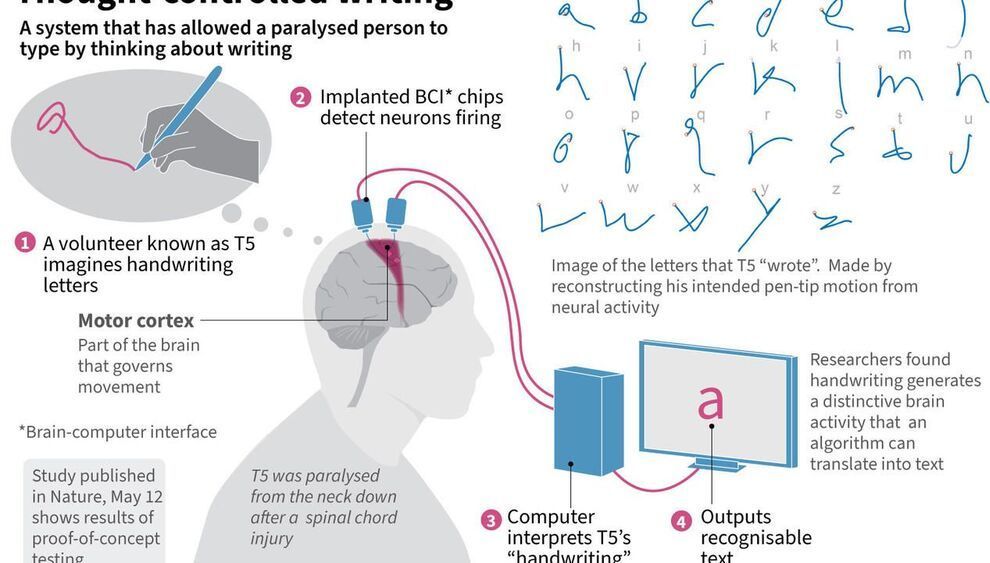

Paralysed from the neck down, the man stares intently at a screen. As he imagines handwriting letters, they appear before him as typed text thanks to a new brain implant.

The 65-year-old is “typing” at a speed similar to his peers tapping on a smartphone, using a device that could one day help paralysed people communicate quickly and easily.

Researchers in Singapore have found a way of controlling a Venus flytrap using electric signals from a smartphone, an innovation they hope will have a range of uses from robotics to employing the plants as environmental sensors.

Luo Yifei, a researcher at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University (NTU), showed in a demonstration how a signal from a smartphone app sent to tiny electrodes attached to the plant could make its trap close as it does when catching a fly.

“Plants are like humans, they generate electric signals, like the ECG (electrocardiogram) from our hearts,” said Luo, who works at NTU’s School of Materials Science and Engineering.

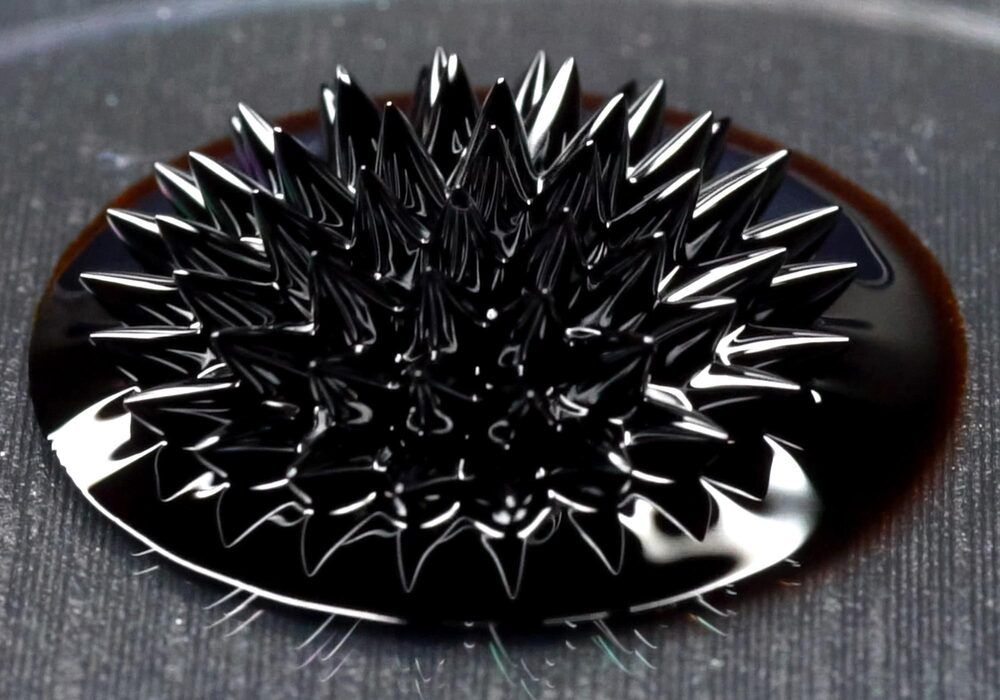

The findings could lead to faster, more secure memory storage, in the form of antiferromagnetic bits.

When you save an image to your smartphone, those data are written onto tiny transistors that are electrically switched on or off in a pattern of “bits” to represent and encode that image. Most transistors today are made from silicon, an element that scientists have managed to switch at ever-smaller scales, enabling billions of bits, and therefore large libraries of images and other files, to be packed onto a single memory chip.

But growing demand for data, and the means to store them, is driving scientists to search beyond silicon for materials that can push memory devices to higher densities, speeds, and security.

The fight against gadget waste is being spurred on by new printable electronics made from wood ink.

The pace of those improvements has slowed, but International Business Machines Corp on Thursday said that silicon has at least one more generational advance in store.

IBM introduced what it says is the world’s first 2-nanometer chipmaking technology. The technology could be as much as 45% faster than the mainstream 7-nanometer chips in many of today’s laptops and phones and up to 75% more power efficient, the company said.

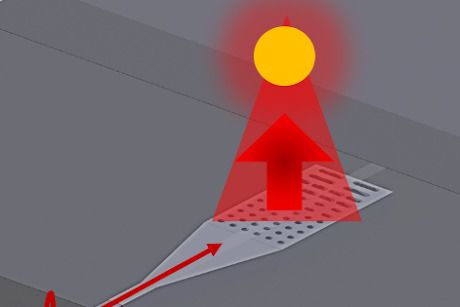

In work that could someday turn cell phones into sensors capable of detecting viruses and other minuscule objects, MIT researchers have built a powerful nanoscale flashlight on a chip.

Their approach to designing the tiny light beam on a chip could also be used to create a variety of other nano flashlights with different beam characteristics for different applications. Think of a wide spotlight versus a beam of light focused on a single point.

For many decades, scientists have used light to identify a material by observing how that light interacts with the material. They do so by essentially shining a beam of light on the material, then analyzing that light after it passes through the material. Because all materials interact with light differently, an analysis of the light that passes through the material provides a kind of “fingerprint” for that material. Imagine doing this for several colors — i.e., several wavelengths of light — and capturing the interaction of light with the material for each color. That would lead to a fingerprint that is even more detailed.

One of the interesting consequences of the emergent upshift in visual systems is that all streetlights, car headlights and other external sources of lighting will no longer be needed within around a decade. This will not only make astronomers happy, since they will be able to see the dark skies again but will simplify urban infrastructure. The three convergent elements making this change of affairs come about are the following:

1) Quanta Image Sensors, whether of the SPAD or the CIS-QIS versions are expected to become widely available within 5 to 10 years. Unlike the CMOS image sensors in billions of cell-phone cameras, which only register packets of the incoming light, these sensors can register single photons of light. The most versatile of these are the QIS sensors being developed by Fossum—who also developed the CMOS sensor—wherein a single jot\.

Demonstrating single-photon sensitivity at room temperature without avalanche multiplication, QIS technology offers sub-diffraction-limited pixel sizes and many degrees of freedom in computing the reconstruction of the image to emphasize resolution, sensitivity, and motion-deblur.