In the future, circuits and systems modelled on human brains could end up in everything from supercomputers to everyday smartphones.

In the future, circuits and systems modelled on human brains could end up in everything from supercomputers to everyday smartphones.

I have often talked about the Many-Worlds or Everett approach to quantum mechanics — here’s an explanatory video, an excerpt from From Eternity to Here, and slides from a talk. But I don’t think I’ve ever explained as persuasively as possible why I think it’s the right approach. So that’s what I’m going to try to do here. Although to be honest right off the bat, I’m actually going to tackle a slightly easier problem: explaining why the many-worlds approach is not completely insane, and indeed quite natural. The harder part is explaining why it actually works, which I’ll get to in another post.

Any discussion of Everettian quantum mechanics (“EQM”) comes with the baggage of pre-conceived notions. People have heard of it before, and have instinctive reactions to it, in a way that they don’t have to (for example) effective field theory. Hell, there is even an app, universe splitter, that lets you create new universes from your iPhone. (Seriously.) So we need to start by separating the silly objections to EQM from the serious worries.

The basic silly objection is that EQM postulates too many universes. In quantum mechanics, we can’t deterministically predict the outcomes of measurements. In EQM, that is dealt with by saying that every measurement outcome “happens,” but each in a different “universe” or “world.” Say we think of Schrödinger’s Cat: a sealed box inside of which we have a cat in a quantum superposition of “awake” and “asleep.” (No reason to kill the cat unnecessarily.) Textbook quantum mechanics says that opening the box and observing the cat “collapses the wave function” into one of two possible measurement outcomes, awake or asleep. Everett, by contrast, says that the universe splits in two: in one the cat is awake, and in the other the cat is asleep. Once split, the universes go their own ways, never to interact with each other again.

Using ultrafast laser flashes, physicists from the Max Planck Institute have generated the fastest electric current that has ever been measured inside a solid material.

In the field of electronics, the principle ‘the smaller, the better’ applies. Some building blocks of computers or mobile phones, however, have become nearly as small today as only a few atoms. It is therefore hardly possible to reduce them any further.

Another factor for the performance of electronic devices is the speed at which electric currents oscillate. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics have now created electric currents inside solids which exceed the frequency of visible light by more than ten times They made electrons in silicon dioxide oscillate with ultrafast laser pulses. The conductivity of the material which is typically used as an insulator was increased by more than 19 orders of magnitude.

It would be the ultimate user interface: a device the size of two stacked nickels that allows your thoughts to control computers. The only catch is it’ll have to be implanted in your brain.

Google could have a record of everything you have said around it for years, and you can listen to it yourself.

The company quietly records many of the conversations that people have around its products.

The feature works as a way of letting people search with their voice, and storing those recordings presumably lets Google improve its language recognition tools as well as the results that it gives to people.

The idea of storing digital data in DNA seems like science fiction. At first glance, it might not seem obvious that a molecule can store data. The term “data storage” conjures up images of physical artifacts like CDs and data centers, not a microscopic molecule like DNA. But there are a number of reasons why DNA is an exciting option for information storage.

The status quo

We’re in the midst of a data explosion. We create vast amounts of information via our estimated 17 billion internet-connected devices: smartphones, cars, health trackers, and all other devices. As we continue to add sensors and network connectivity to physical devices we will produce more and more data. Similarly, as we bring online the 4.2 billion people who are currently offline, we will produce more and more data.

“AT&T and Time Warner are reportedly in talks about a potential merger.”

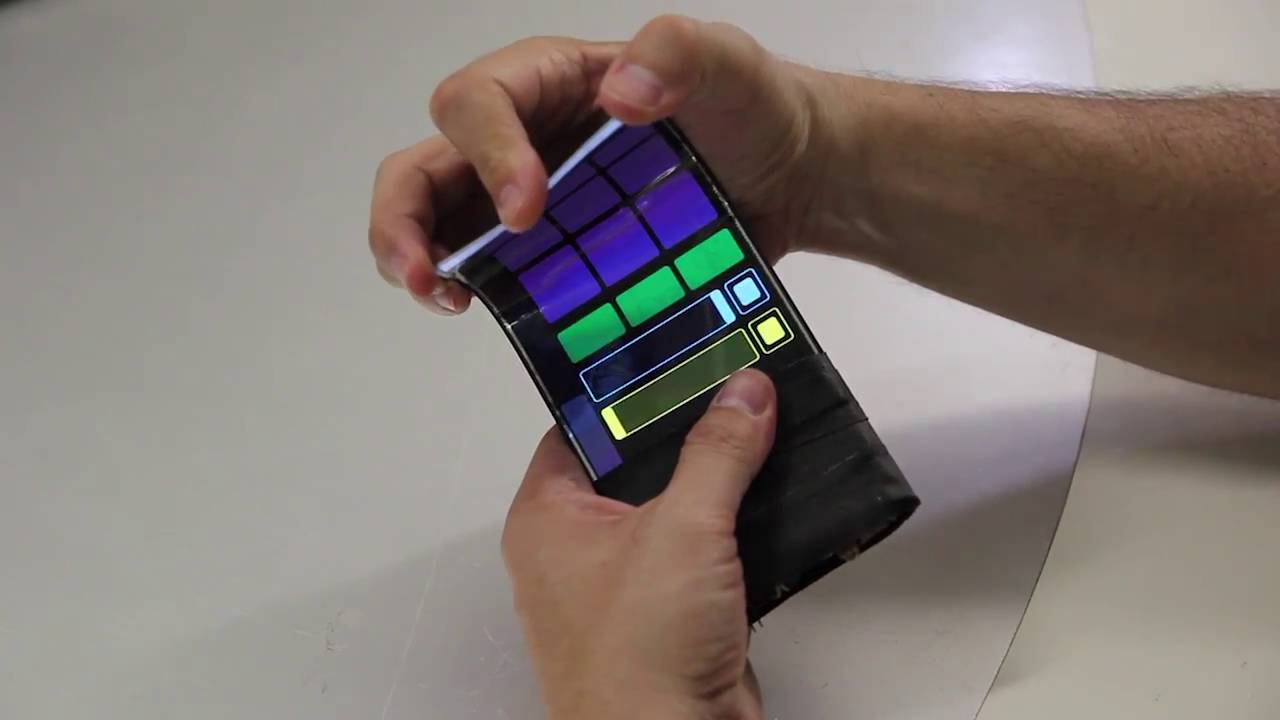

Earlier this year, a team from Queen’s University in Canada demonstrated a smartphone prototype called ReFlex that had a flexible display capable of flipping virtual book pages in response to what were dubbed bend gestures. Researchers from the same Human Media Lab have now developed a similar device called the WhammyPhone that’s claimed to be the world’s first virtual musical instrument for flexible phones.

The WhammyPhone prototype sports a 1920 x 1080 pixel full high-definition Flexible Organic Light Emitting Diode (FOLED) touchscreen display and, like the ReFlex device, includes a bend sensor. This means that a user can manipulate the sound of electronically-generated instruments such as a guitar or violin by bending, squeezing or twisting the “smartphone.”

“WhammyPhone is a completely new way of interacting with sound using a smartphone,” said Dr. Roel Vertegaal, Professor of Human-Computer Interaction at Queen’s University. “It allows for the kind of expressive input normally only seen in traditional musical instruments.”

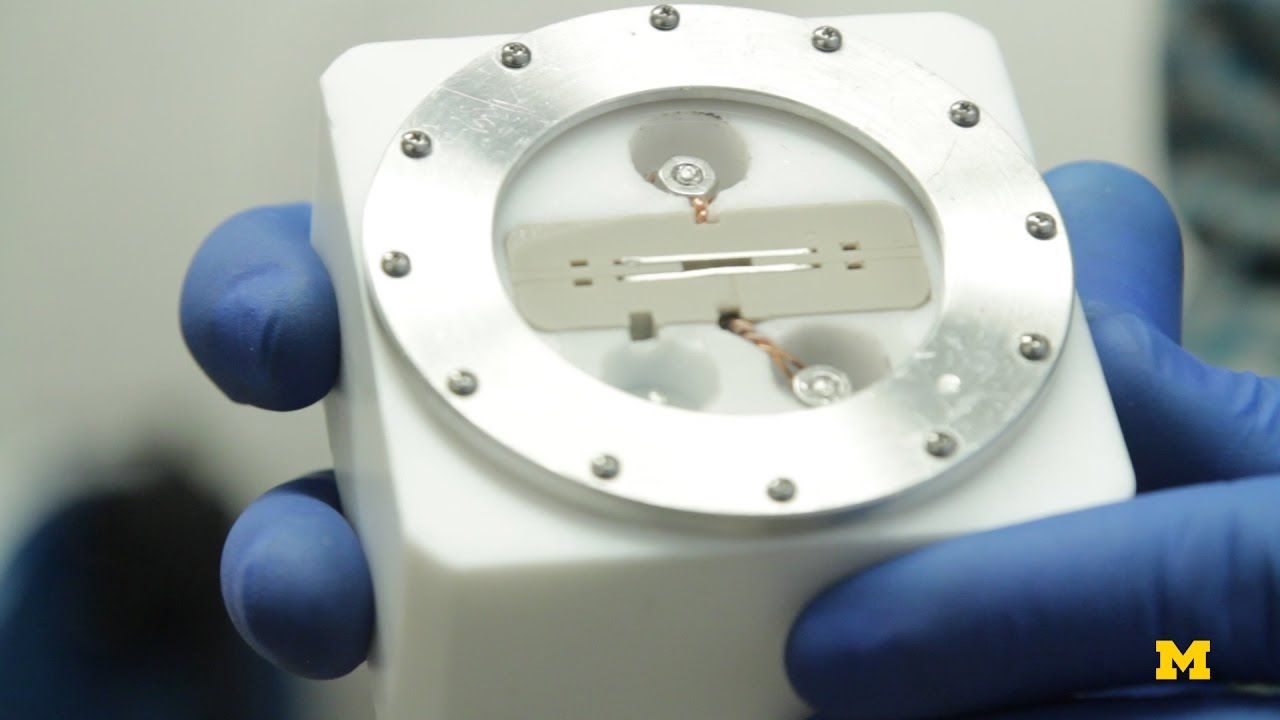

In a great example of a low-cost research solution that could deliver big results, University of Michigan scientists have created a window for lithium-based batteries in order to film them as they charge and discharge.

The future of lithium-ion batteries is limited, says University of Michigan researcher Neil Dasgupta, because the chemistry cannot be pushed much further than it already has. Next-generation lithium cells will likely use lithium air and lithium sulfur chemistries. One of the big hurdles to be overcome in making these batteries practical is dendrites — tiny branch-like structures of lithium that form on the electrodes.

Dendrites can pierce cell walls or limit the lithium’s potential. Neither is good for battery efficiency and can even lead to fires and explosions like those that have plagued the Samsung Galaxy Note 7 – though the jury is still out on exactly what caused the Note 7’s well documented woes.

Traditional lithium-ion batteries may be on the way out, as scientists continue to overcome the obstacles holding back the longer-lasting lithium-oxygen batteries. The main issue is lack of efficiency and the build-up of lithium peroxide, which reduces the electrodes’ effectiveness. But now a team at Yale has used a molecule found in blood as a catalyst that not only improved the lithium-oxygen function, but may help reduce biowaste.

Lithium-oxygen, or lithium-air batteries, have the potential to hold a charge for much longer than traditional lithium-ion batteries and extend the life of devices like phones to several weeks before they’d need to be recharged. But before those dreams can become a reality, the problems of efficiency and lithium peroxide build-up need to be solved.

Previous studies have tried to fight lithium peroxide by keeping the oxygen in the cell as a solid, and by modifying the electrode to produce lithium superoxide instead. In this case, the Yale researchers were looking for a new catalyst that allowed lithium oxide in the cell to decompose back into lithium ions and gaseous oxygen, and they found one in an unexpected place: animal blood.