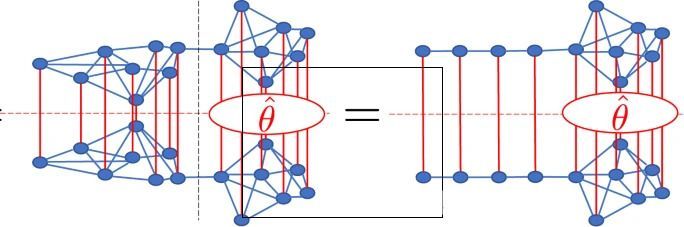

Quantum computing algorithms can simulate infinitely-large quantum systems thanks to mathematical tools known as tensor networks.

Math about black holes:

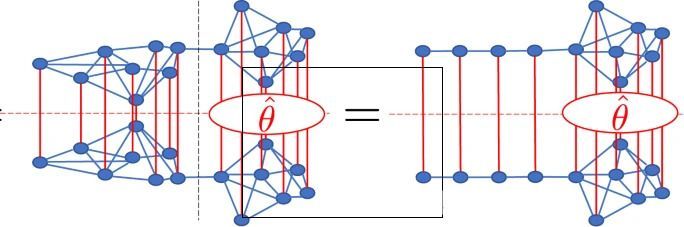

If you’ve been following the arXiv, or keeping abreast of developments in high-energy theory more broadly, you may have noticed that the longstanding black hole information paradox seems to have entered a new phase, instigated by a pair of papers [1, 2] that appeared simultaneously in the summer of 2019. Over 200 subsequent papers have since appeared on the subject of “islands”—subleading saddles in the gravitational path integral that enable one to compute the Page curve, the signature of unitary black hole evaporation. Due to my skepticism towards certain aspects of these constructions (which I’ll come to below), my brain has largely rebelled against boarding this particular hype train. However, I was recently asked to explain them at the HET group seminar here at Nordita, which provided the opportunity (read: forced me) to prepare a general overview of what it’s all about. Given the wide interest and positive response to the talk, I’ve converted it into the present post to make it publicly available.

Well, most of it: during the talk I spent some time introducing black hole thermodynamics and the information paradox. Since I’ve written about these topics at length already, I’ll simply refer you to those posts for more background information. If you’re not already familiar with firewalls, I suggest reading them first before continuing. It’s ok, I’ll wait.

Done? Great; let me summarize the pre-island state of affairs with the following two images, which I took from the post-island review [3] (also worth a read):

Circa 2014

Physicists have verified a key prediction of Albert Einstein’s special theory of relativity with unprecedented accuracy. Experiments at a particle accelerator in Germany confirm that time moves slower for a moving clock than for a stationary one.

The work is the most stringent test yet of this ‘time-dilation’ effect, which Einstein predicted. One of the consequences of this effect is that a person travelling in a high-speed rocket would age more slowly than people back on Earth.

Few scientists doubt that Einstein was right. But the mathematics describing the time-dilation effect are “fundamental to all physical theories”, says Thomas Udem, a physicist at the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics in Garching, Germany, who was not involved in the research. “It is of utmost importance to verify it with the best possible accuracy.”

Nathan Seiberg, 64, still does a lot of the electrical work and even some of the plumbing around his house in Princeton, New Jersey. It’s an interest he developed as a kid growing up in Israel, where he tinkered with his car and built a radio.

“I was always fascinated by solving problems and understanding how things work,” he said.

Seiberg’s professional career has been about problem solving, too, though nothing as straightforward as fixing radios. He’s a physicist at the Institute for Advanced Study, and over the course of a long and decorated career he has made many contributions to the development of quantum field theory, or QFT.

Not everything that is true can be proven. This discovery transformed infinity, changed the course of a world war and led to the modern computer. This video is sponsored by Brilliant. The first 200 people to sign up via https://brilliant.org/veritasium get 20% off a yearly subscription.

Special thanks to Prof. Asaf Karagila for consultation on set theory and specific rewrites, to Prof. Alex Kontorovich for reviews of earlier drafts, Prof. Toby ‘Qubit’ Cubitt for the help with the spectral gap, to Henry Reich for the helpful feedback and comments on the video.

▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀

References:

Dunham, W. (2013, July). A Note on the Origin of the Twin Prime Conjecture. In Notices of the International Congress of Chinese Mathematicians (Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 63-65). International Press of Boston. — https://ve42.co/Dunham2013

Conway, J. (1970). The game of life. Scientific American, 223, 4. — https://ve42.co/Conway1970

Churchill, A., Biderman, S., Herrick, A. (2019). Magic: The Gathering is Turing Complete. ArXiv. — https://ve42.co/Churchill2019

Neil deGrasse Tyson explains the early state of our Universe. At the beginning of the universe, ordinary space and time developed out of a primeval state, where all matter and energy of the entire visible universe was contained in a hot, dense point called a gravitational singularity. A billionth the size of a nuclear particle.

While we can not imagine the entirety of the visible universe being a billion times smaller than a nuclear particle, that shouldn’t deter us from wondering about the early state of our universe. However, dealing with such extreme scales is immensely counter-intuitive and our evolved brains and senses have no capacity to grasp the depths of reality in the beginning of cosmic time. Therefore, scientists develop mathematical frameworks to describe the early universe.

Neil deGrasse Tyson also mentions that our senses are not necessarily the best tools to use in science when uncovering the mysteries of the Universe.

It is interesting to note that in the early Universe, high densities and heterogeneous conditions could have led sufficiently dense regions to undergo gravitational collapse, forming black holes. These types of Primordial black holes are hypothesized to have formed soon after the Big Bang. Going from one mystery to the next, some evidence suggests a possible Link Between Primordial Black Holes and Dark Matter.

In modern physics, antimatter is made up of elementary particles, each of which has the same mass as their corresponding matter counterparts — protons, neutrons and electrons — but the opposite charges and magnetic properties.

A collision between any particle and its anti-particle partner leads to their mutual annihilation, giving rise to various proportions of intense photons, gamma rays and neutrinos. The majority of the total energy of annihilation emerges in the form of ionizing radiation. If surrounding matter is present, the energy content of this radiation will be absorbed and converted into other forms of energy, such as heat or light. The amount of energy released is usually proportional to the total mass of the collided matter and antimatter, in accordance with Einstein’s mass–energy equivalence equation.

Once researchers have done the hard work of translating a set of mathematical concepts into a proof assistant, the program generates a library of computer code that can be built on by other researchers and used to define higher-level mathematical objects. In this way, proof assistants can help to verify mathematical proofs that would otherwise be time-consuming and difficult, perhaps even practically impossible, for a human to check.

Proof assistants have long had their fans, but this is the first time that they have played a major role at the cutting edge of a field, says Kevin Buzzard, a mathematician at Imperial College London who was part of a collaboration that checked Scholze and Clausen’s result. “The big remaining question was: can they handle complex mathematics?” Says Buzzard. “We showed that they can.”

And it all happened much faster than anyone had imagined. Scholze laid out his challenge to proof-assistant experts in December 2020, and it was taken up by a group of volunteers led by Johan Commelin, a mathematician at the University of Freiburg in Germany. On 5 June — less than six months later — Scholze posted on Buzzard’s blog that the main part of the experiment had succeeded. “I find it absolutely insane that interactive proof assistants are now at the level that, within a very reasonable time span, they can formally verify difficult original research,” Scholze wrote.

Physics World

Quantum mechanics describes this frustration by suggesting that the orientation of the spins is not rigid. Instead, it constantly changes direction in a fluid-like way to produce an entangled ensemble of spin-ups and spin-downs. Thanks to this behaviour, a spin liquid will remain in a liquid state even at temperatures near absolute zero, where most materials usually freeze solid.

The holon and the spinon

To describe this behaviour in mathematical terms, the late Nobel laureate Philip W Anderson, who predicted the existence of spin liquids in 1973, proposed that in the quantum regime, an electron might in fact be composed of two distinct particles. The first, known as a “holon”, would bear the electron’s negative charge, while the second “spinon” particle would carry its spin. Anderson later suggested that this spin-charge separation might provide a microscopic mechanism to explain the high superconducting transition temperatures (Tc) that were observed in copper oxides, or cuprates, beginning in the late 1980s.