Realistic climate simulations require huge reserves of computational power. An LMU study now shows that new algorithms allow interactions in the atmosphere to be modeled more rapidly without loss of reliability.

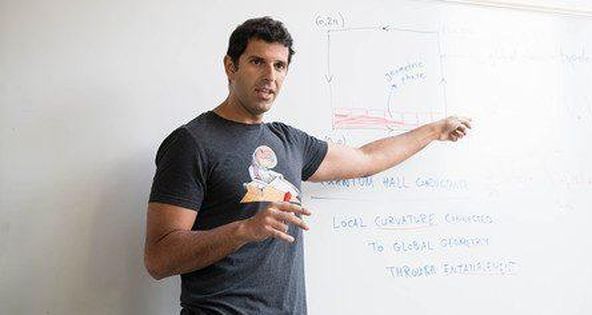

Forecasting global and local climates requires the construction and testing of mathematical climate models. Since such models must incorporate a plethora of physical processes and interactions, climate simulations require enormous amounts of computational power. And even the best models inevitably have limitations, since the phenomena involved can never be modeled in sufficient detail. In a project carried out in the context of the DFG-funded Collaborative Research Center “Waves to Weather”, Stephan Rasp of the Institute of Theoretical Meteorology at LMU (Director: Professor George Craig) has now looked at the question of whether the application of artificial intelligence can improve the efficacy of climate modelling. The study, which was performed in collaboration with Professor Mike Pritchard of the University of California at Irvine und Pierre Gentine of Columbia University in New York, appears in the journal PNAS.

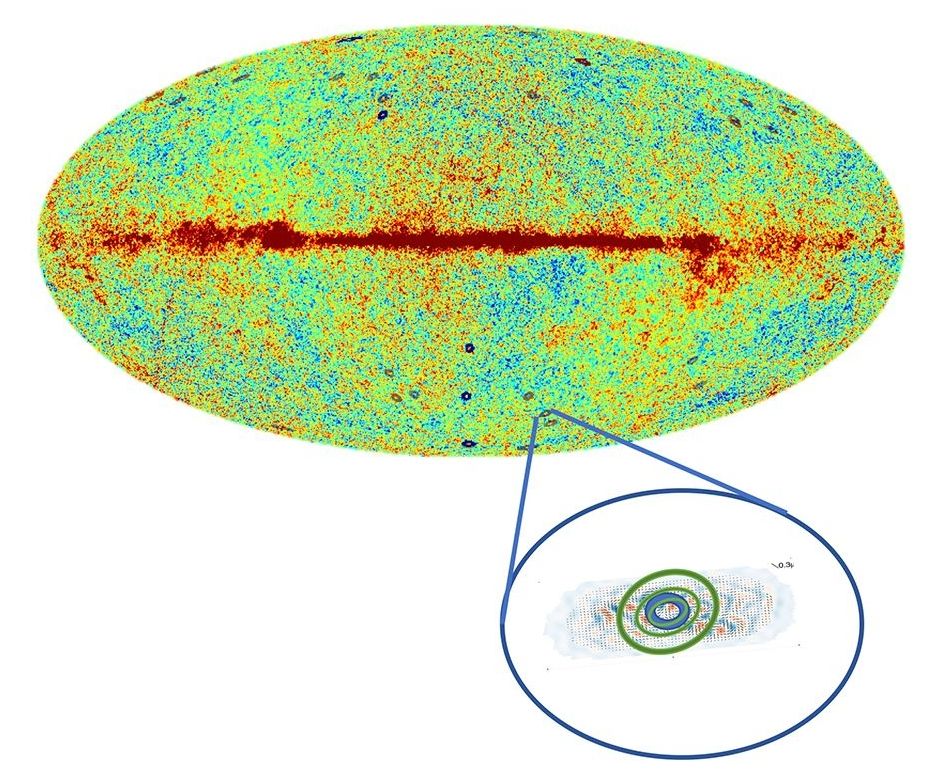

General circulation models typically simulate the global behavior of the atmosphere on grids whose cells have dimensions of around 50 km. Even using state-of-the-art supercomputers the relevant physical processes that take place in the atmosphere are simply too complex to be modelled at the necessary level of detail. One prominent example concerns the modelling of clouds which have a crucial influence on climate. They transport heat and moisture, produce precipitation, as well as absorb and reflect solar radiation, for instance. Many clouds extend over distances of only a few hundred meters, much smaller than the grid cells typically used in simulations – and they are highly dynamic. Both features make them extremely difficult to model realistically. Hence today’s climate models lack at least one vital ingredient, and in this respect, only provide an approximate description of the Earth system.