Researchers have developed a new printer that produces digital 3D holograms with an unprecedented level of detail and realistic color. The new printer could be used to make high-resolution color recreations of objects or scenes for museum displays, architectural models, fine art or advertisements that do not require glasses or special viewing aids.

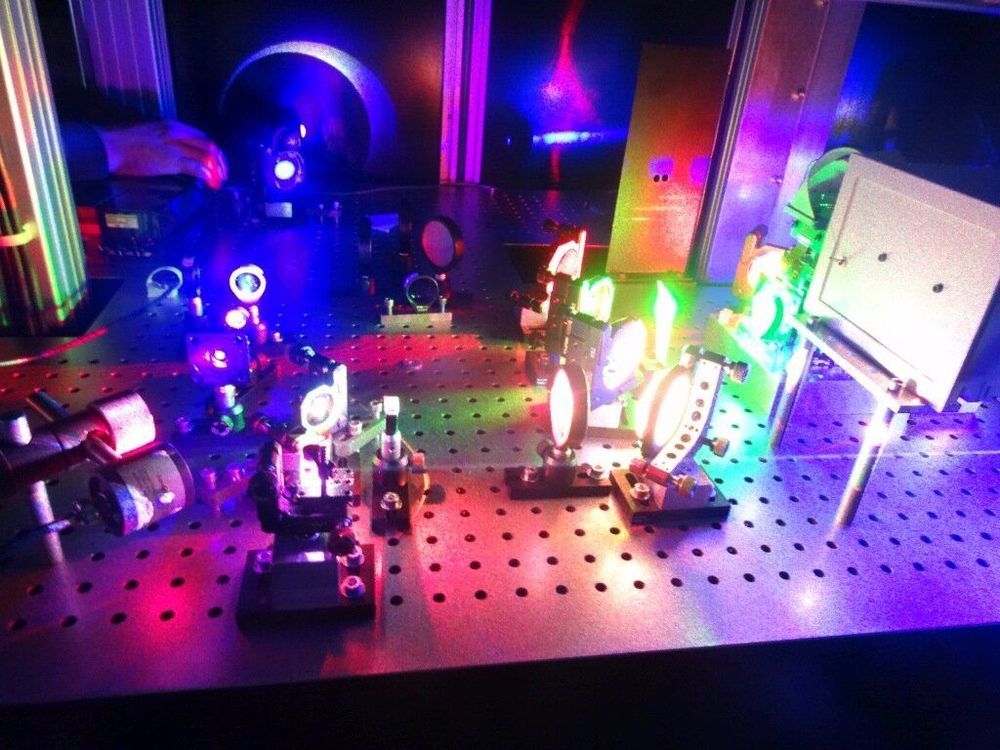

“Our 15-year research project aimed to build a hologram printer with all the advantages of previous technologies while eliminating known drawbacks such as expensive lasers, slow printing speed, limited field of view and unsaturated colors,” said research team leader Yves Gentet from Ultimate Holography in France. “We accomplished this by creating the CHIMERA printer, which uses low-cost commercial lasers and high-speed printing to produce holograms with high-quality color that spans a large dynamic range.”

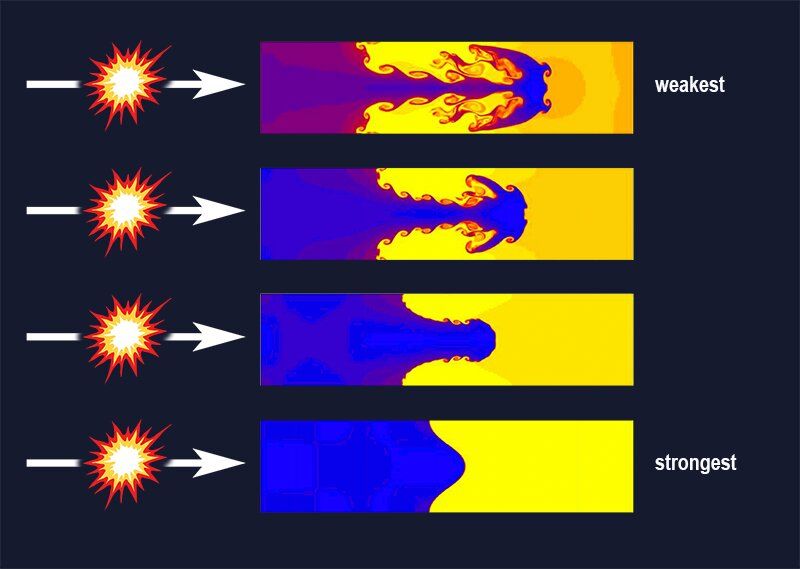

In The Optical Society (OSA) journal Applied Optics, the researchers describe the new printer, which creates holograms with wide fields of view and full parallax on a special photographic material they designed. Full parallax holograms reconstruct an object so that it is viewable in all directions, in this case with a field of view spanning 120 degrees.