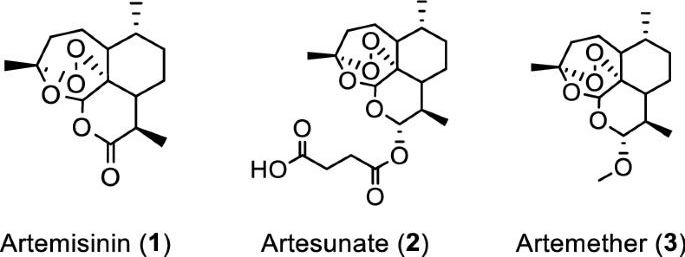

Artemisia annua plants grown from a cultivated seed line in Kentucky, USA, were extracted using either absolute ethanol or distilled water at 50 °C for 200 min and analyzed, as described in “Materials and methods” and Supplementary Information (Figures S1 and S2). Solids were removed by filtration and the solvents were evaporated. The extracted materials were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (ethanol extract) or a DMSO: water mixture (3:1 for aqueous extract) and filtered (see supporting information for details). Artemisinin (Fig. 1, (1)) was synthesized and purified following a published procedure or purchased17, while artesunate (Fig. 1, (2)) and artemether (Fig. 1, (3)) were only obtained from commercial sources.

Initial experiments were carried out at FU Berlin, Germany. To initially screen whether extracts and pure artemisinin were active against SARS-CoV-2, their antiviral activity was tested by pretreating VeroE6 cells at different time points during 120 min with selected concentrations of the extracts or compounds prior to infection with the first European SARS-CoV-2 isolated in München (SARS-CoV-2/human/Germany/BavPat 1/2020). The virus-drug mixture was then removed and cells were overlaid with medium containing 1.3% carboxymethylcellulose to prevent virus release into the medium. DMSO was used as a negative control. Plaque numbers were determined either by indirect immunofluorescence using a mixture of antibodies to SARS-CoV N protein18 or by staining with crystal violet19. The addition of either ethanolic or aqueous A. annua extracts prior to virus addition resulted in reduced plaque formation in a concentration dependent manner, while artemisinin exhibited little antiviral activity (Supplemental Tables S1 – S8).

Concentration–response experiments were carried out at Copenhagen University Hospital-Hvidovre. In these experiments the Danish SARS-CoV-2 isolate SARS-CoV-2/human/Denmark/DK-AHH1/2020 was used employing a 96-well plate based concentration–response antiviral treatment assay, allowing for multiple replicates per concentration, as described in “Materials and methods” and Supplementary Information (Figures S3 and S4)20,21. Seven replicates were measured at each concentration and a range of concentrations was evaluated to increase data accuracy when compared to the plaque-reduction assay, which was carried out in duplicates. Extracts or compounds were added to VeroE6 cells either 1.5 h prior to (pretreatment (pt)) or 1 h post infection (treatment (t)), respectively, followed by a 2-day incubation of virus with extracts or compounds. Both protocols yielded similar results, with slightly lower median effective concentration (EC50) values observed for treatment assays.