Your space questions, answered.

New post!

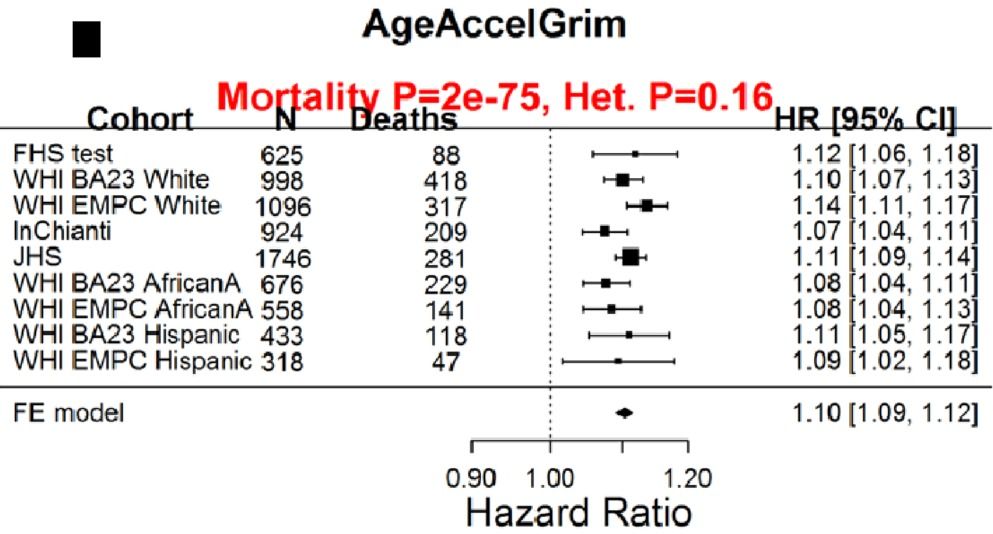

Having a faster rate of epigenetic aging, as measured by the epigenetic age metric, AgeAccelGrim, is associated with a significantly increased risk of death for all causes in a variety of cohorts, including the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study, the InChianti study, the Jackson Heart Study (JHS), and collectively, when evaluated as a meta-analysis (Lu et al. 2019):

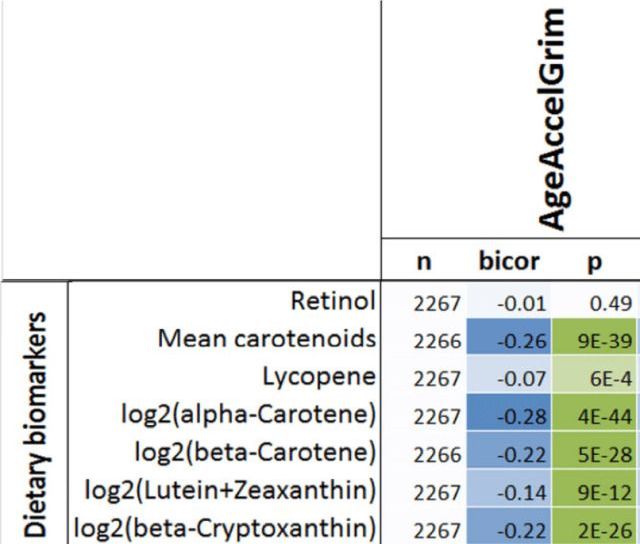

With the goal of minimizing disease risk and maximizing longevity, can epigenetic aging be slowed? Shown below is the correlation between dietary components with AgeAccelGrim. Dietary factors that were significantly associated (the column labelled, “p”) with a younger epigenetic age were carbohydrate intake, dairy, whole grains, fruit, and vegetables. In contrast, dietary fat intake and red meat were associated with older epigenetic ages (Lu et al. 2019):

Families with long, healthy life spans focus of $68 million grant~ via Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis https://medicine.wustl.edu/news/families-with-long-healthy-life-spans-focus-of-68-million-grant/

A few hundred of the thousands of proteins circulating in our blood turn out to be a fairly accurate forecaster of a person’s age, scientists reported Thursday — though one’s biological age, which doesn’t always match one’s number of years.

This “proteomic clock,” as the researchers call it, relies on measurements of levels of the proteins, which rise and fall over the years. While it’s a nifty discovery, for now it remains just that. Researchers need to first develop a much better understanding of these proteins; if they can, they said, it might be possible to one day look at their levels to gauge the success of drugs being tested in clinical trials, or even to develop a therapy from a cocktail of proteins that could act like a rejuvenation boost or improve health.

“Why are these proteins so tightly linked to aging?” said Tony Wyss-Coray, professor of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford and the senior author of the paper4, which was published Thursday in the journal Nature Medicine.

A few hundred of the thousands of proteins circulating in our blood turn out to be a fairly accurate forecaster of a person’s age, scientists reported Thursday — though one’s biological age, which doesn’t always match one’s number of years.

This “proteomic clock,” as the researchers call it, relies on measurements of levels of the proteins, which rise and fall over the years. While it’s a nifty discovery, for now it remains just that. Researchers need to first develop a much better understanding of these proteins; if they can, they said, it might be possible to one day look at their levels to gauge the success of drugs being tested in clinical trials, or even to develop a therapy from a cocktail of proteins that could act like a rejuvenation boost or improve health.

“Why are these proteins so tightly linked to aging?” said Tony Wyss-Coray, professor of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford and the senior author of the paper4, which was published Thursday in the journal Nature Medicine.

Ethical concerns about new and emerging technologies that could significantly extend human lifespans generally focus on their potential impact on individuals and the permissibility of providing such treatment options. Because these technologies might also prompt us to assess and balance interests of different individuals and groups, given resource and production limitations, life-extension technologies provoke profound conversations about the nature and value of traditional conceptions of humanity.

Life extension requires careful consideration of resource scarcity, justice, and what, if anything, is intrinsic to the experiences we define as human.

The blood-borne signs of aging – and indeed, perhaps the causes of aging – make three big shifts around the ages of 34, 60 and 78, a new Stanford-led study has discovered, potentially leading to new diagnostic tests and avenues of anti-aging research.

The study measured levels of nearly 3,000 individual proteins in the plasma of small blood samples from 4,263 people aged between 18 and 95, and found that 1,379 of these proteins varied significantly with a subject’s age. Indeed, with information about levels of just 373 of these proteins, the researchers found they could predict a subject’s age “with great accuracy,” and an even smaller subset of just nine proteins could do a “passable” job.

Proteins are the body’s workhorses, carrying out instructions from all the body’s cells. Changes in their levels in our blood reflect the starting, stopping and changing of different biological processes. The researchers found that these changes were often quite sudden – levels of a protein would remain stable in the blood for years, and then rapidly plunge or leap, rather than showing a steady increase or decline.

A type of artificial intelligence technique is now being used to develop new drugs and therapies and could perhaps even help to solve aging.

An urgent need for aging biomarkers

There has long been an urgent need in our field to develop increasingly accurate biomarkers of aging so that the efficacy of interventions can be gauged. Deep learning is one of the more recent techniques being applied in the search for aging biomarkers.