Nice. My friend Alex Zhavoronkov will appreciate this article.

Feb. 16 (UPI) — Researchers at McGill University in Montreal have found that targeting the internal circadian or biological clock of cancer cells can affect growth.

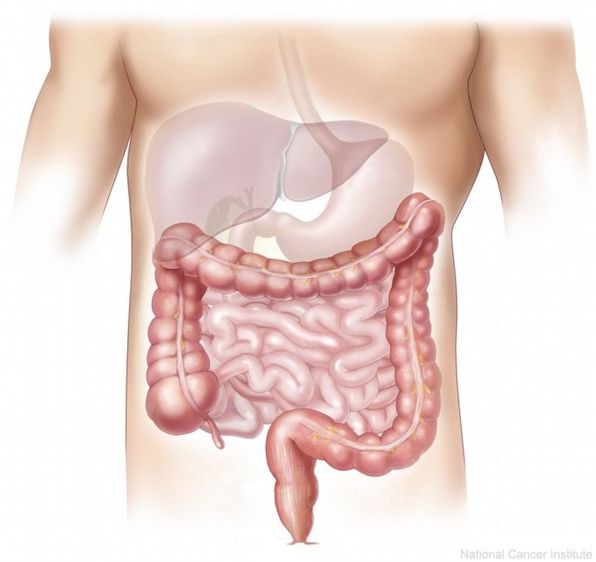

Most cells in the human body have an internal clock that sets a rhythm for activities of organs depending on the time of day. However, this internal clock in cancer cells does not function at all or malfunctions.

“There were indications suggesting that the malfunctioning clock contributed to rapid tumor growth, but this had never been demonstrated,” Nicolas Cermakian, a professor in the department of psychiatry at McGill University, director of the Laboratory of Molecular Chronobiology at the Douglas Mental Health University Institute and author of the study, said in a press release. “Thanks to the use of a chemical or a thermic treatment, we succeeded in ‘repairing’ these cells’ clock and restoring it to its normal functioning. In these conditions, tumor growth drops nearly in half.”