Upon an otherwise unruly landscape of choppy sea and craggy peaks, the salmon farms that dot many of Norway’s remote fjords impose a neat geometry. The circular pens are placid on the surface, but hold thousands of churning fish, separated by only a net from their wild counterparts. And that is precisely the conundrum. Although the pens help ensure the salmon’s welfare by mimicking the fish’s natural habitat, they also sometimes allow fish to escape, a problem for both the farm and the environment.

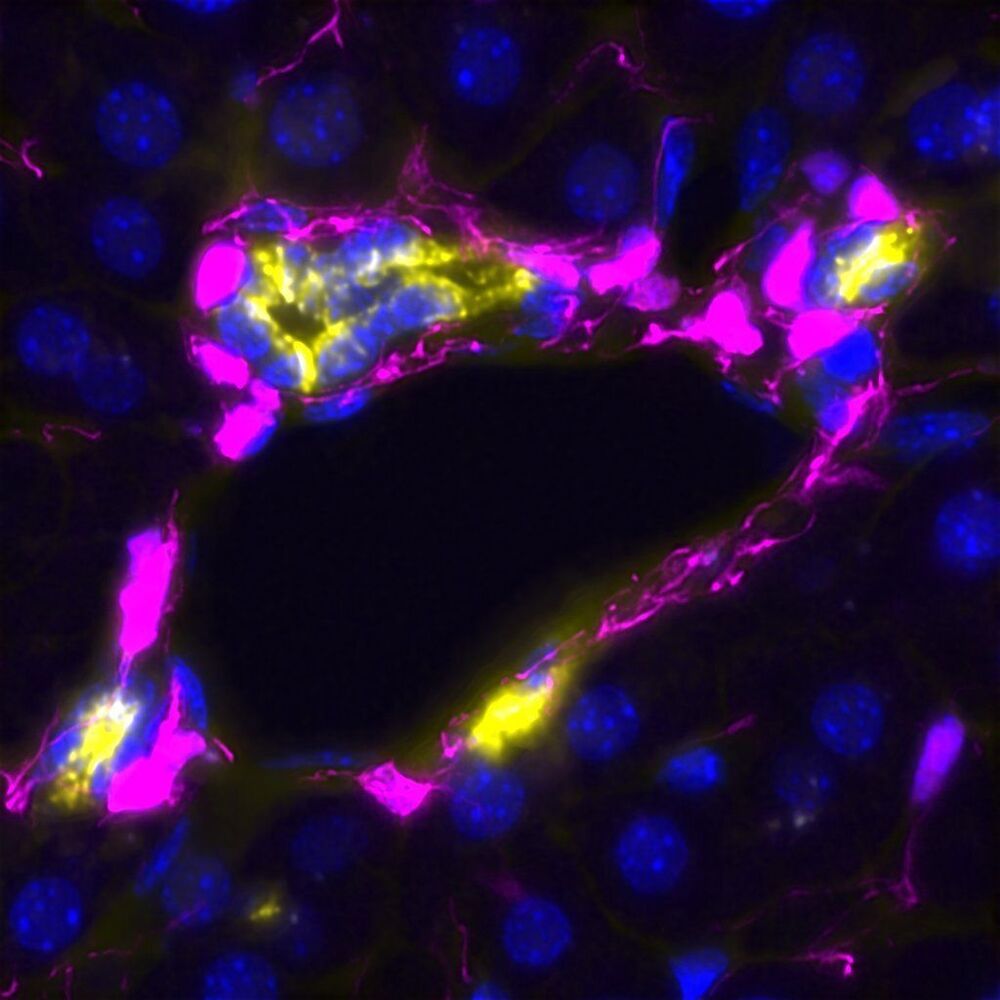

In an attempt to prevent escaped fish from interbreeding with their wild counterparts and threatening the latter’s genetic diversity, molecular biologist Anna Wargelius and her team at the Institute of Marine Research in Norway have spent years working on ways to induce sterility in Atlantic salmon. Farmed salmon that cannot reproduce, after all, pose no threat to the gene pool of wild stocks, and Wargelius has successfully developed a technique that uses the gene-editing technology Crispr to prevent the development of the cells that would otherwise generate functioning sex organs.

In fact, Wargelius’ team was a little too successful. To be financially viable, commercial fish farms need at least some of their stock to reproduce. So the scientists went a step further, developing a method of temporarily reversing the modification they had already made. They’ve created what they call “sterile parents.”