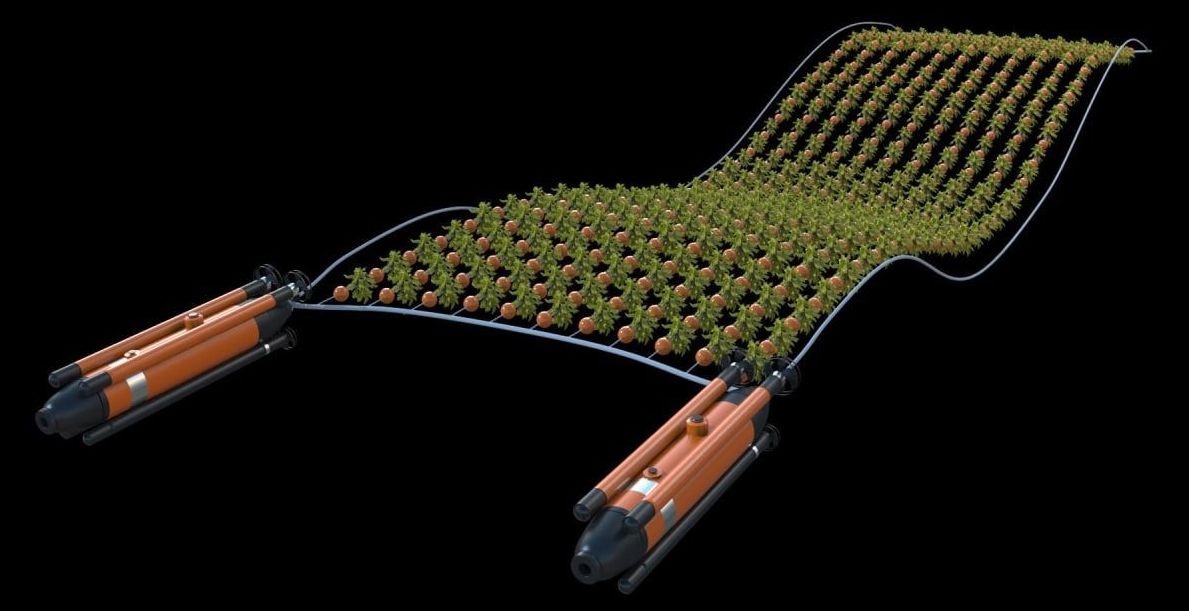

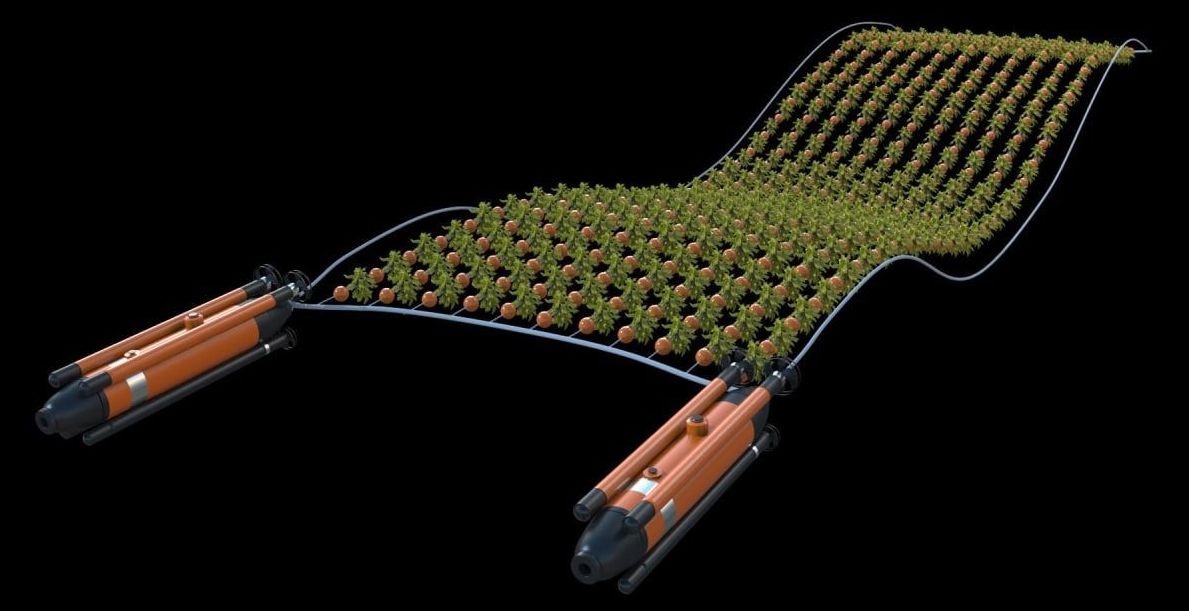

By using elevators to grow kelp farther out in ocean waters, Marine BioEnergy thinks it can grow enough seaweed to make a dent in the fuel market.

By using elevators to grow kelp farther out in ocean waters, Marine BioEnergy thinks it can grow enough seaweed to make a dent in the fuel market.

Now a long lasting ice cream which does not melt soon is available and being sold in Japan, which is scientifically proven.

My new Op-Ed for The San Francisco Chronicle: http://www.sfchronicle.com/opinion/openforum/article/Chip-implants-make-humans-more-efficient-12003194.php #transhumanism

Wisconsin company Three Square Market recently announced it will become the first U.S. company to offer its employees chip implants that can be scanned at security entrances, carry medical information and even purchase candy in some vending machines. A company in Europe already did this last year.

For many people, it sounds crazy to electively have a piece of technology embedded in their body simply for convenience’s sake. But a growing number of Americans are doing it, including me.

I got my RFID implant two years ago, and now I use it to send text messages, bypass security codes on my computer, and open my front door. Soon I’ll get the software to start my car, and then my life will be totally keyless.

The type of chip implants in humans varies depending on the manufacturer or purpose of the device. A few hundred thousand people around the world have cochlear implants, which allow deaf people to hear. Others have implants to help with Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s or even depression. A growing number of transhumanists — people who want to use radical technology in their bodies — have the $60 implant I have. It’s tiny, about the size of a grain of rice, and is injected into the body by a syringe. The injection process — usually in the hand near the thumb — is often bloodless and takes seconds to complete.

What if traffic flowed through our streets as smoothly and efficiently as blood flows through our veins? Transportation geek Wanis Kabbaj thinks we can find inspiration in the genius of our biology to design the transit systems of the future. In this forward-thinking talk, preview exciting concepts like modular, detachable buses, flying taxis and networks of suspended magnetic pods that could help make the dream of a dynamic, driverless world into a reality.

“Some people are obsessed by French wines. Others love playing golf or devouring literature. One of my greatest pleasures in life is, I have to admit, a bit special. I cannot tell you how much I enjoy watching cities from the sky, from an airplane window.”

Giant fans start capturing CO2 from the air as the world’s first commercial carbon capture plant goes live.

Researchers at UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) conducted a study in 2012 on rats and found that a diet high in fructose hinders learning skills and memory and also slow down the brain. The researchers found that rats who over-consumed fructose had damaged synaptic activity in the brain, meaning that communication among brain cells was impaired.

Study’s lead author Dr. Fernando Gomez-Pinilla said in a statement that “Insulin is important in the body for controlling blood sugar, but it may play a different role in the brain. Our study shows that a high-fructose diet harms the brain as well as the body.”

In addition to the damaging effects on cognition and mood, sugar also has drug-like effects in the reward system of the brain. Neuroscientist Nicole Avena presented the effect of sugar on our brains and bodies in TED-Ed’s animated installment.

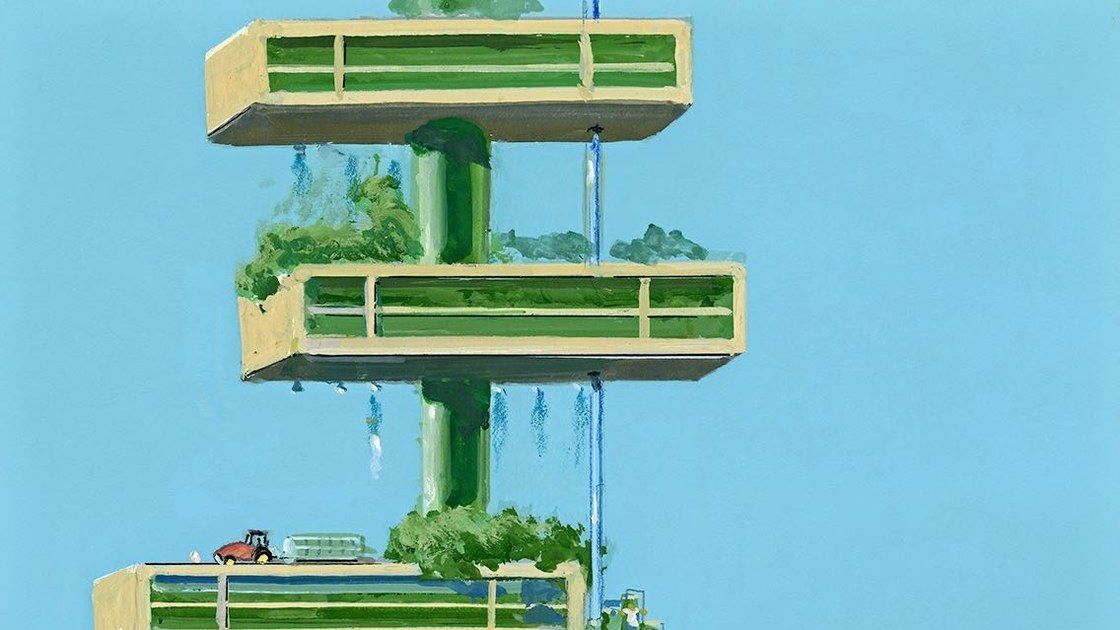

The term “vertical farming” has not been around long. It refers to a method of growing crops, usually without soil or natural light, in beds stacked vertically inside a controlled-environment building. The credit for coining the term seems to belong to Dickson D. Despommier, Ph.D., a professor (now emeritus) of parasitology and environmental science at Columbia University Medical School and the author of “The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century.”

Hearing that Despommier would be addressing an audience of high-school science teachers at Columbia on a recent morning, I arranged to sit in. During the question period, one of the teachers asked a basic question that had also been puzzling me: What are the plants in a soil-free farm made of? Aren’t plants mostly the soil that they grew in? Despommier explained that plants consist of water, mineral nutrients like potassium and magnesium taken from the soil (or, in the case of a vertical farm, from the nutrients added to the water their roots are sprayed with), and carbon, an element plants get from the CO2 in the air and then convert by photosynthesis into sucrose, which feeds the plant, and cellulose, which provides its structure.

In other words, plants create themselves partly out of thin air. Salad greens are about ninety per cent water. About half of the remaining ten per cent is carbon. If AeroFarms’ vertical farm grows a thousand tons of greens a year, about fifty tons of that will be carbon taken from the air.

South Korea will oversee the construction of an integrated agriculture city in Egypt which will feature 50,000 smart greenhouses in addition to desalination and solar power plants.