https://www.youtube.com/attribution_link?a=P-wiCEov7oQ&u=/watch?v=GzGmxPEiGWY&feature=share

Michael B. Fossel, M.D., Ph.D. (born 1950, Greenwich, Connecticut) was a professor of clinical medicine at Michigan State University and is the author of several books on aging, who is best known for his views on telomerase therapy as a possible treatment for cellular senescence. Fossel has appeared on many major news programs to discuss aging and has appeared regularly on National Public Radio (NPR). He is also a respected lecturer, author, and the founder and former editor-in-chief of the Journal of Anti-Aging Medicine (now known as Rejuvenation Research).

Prior to earning his M.D. at Stanford Medical School, Fossel earned a joint B.A. (cum laude) and M.A. in psychology at Wesleyan University and a Ph.D. in neurobiology at Stanford University. He is also a graduate of Phillips Exeter Academy. Prior to graduating from medical school in 1981, he was awarded a National Science Foundation fellowship and taught at Stanford University.

In addition to his position at Michigan State University, Fossel has lectured at the National Institute for Health, the Smithsonian Institution, and at various other universities and institutes in various parts of the world. Fossel served on the board of directors for the American Aging Association and was their executive director.

Fossel has written numerous articles on aging and ethics for the Journal of the American Medical Association and In Vivo, and his first book, entitled Reversing Human Aging was published in 1996. The book garnered favorable reviews from mainstream newspapers as well as Scientific American and was published in six languages. A magisterial academic textbook on by Fossel entitled Cells, Aging, and Human Disease was published in 2004 by Oxford University Press.

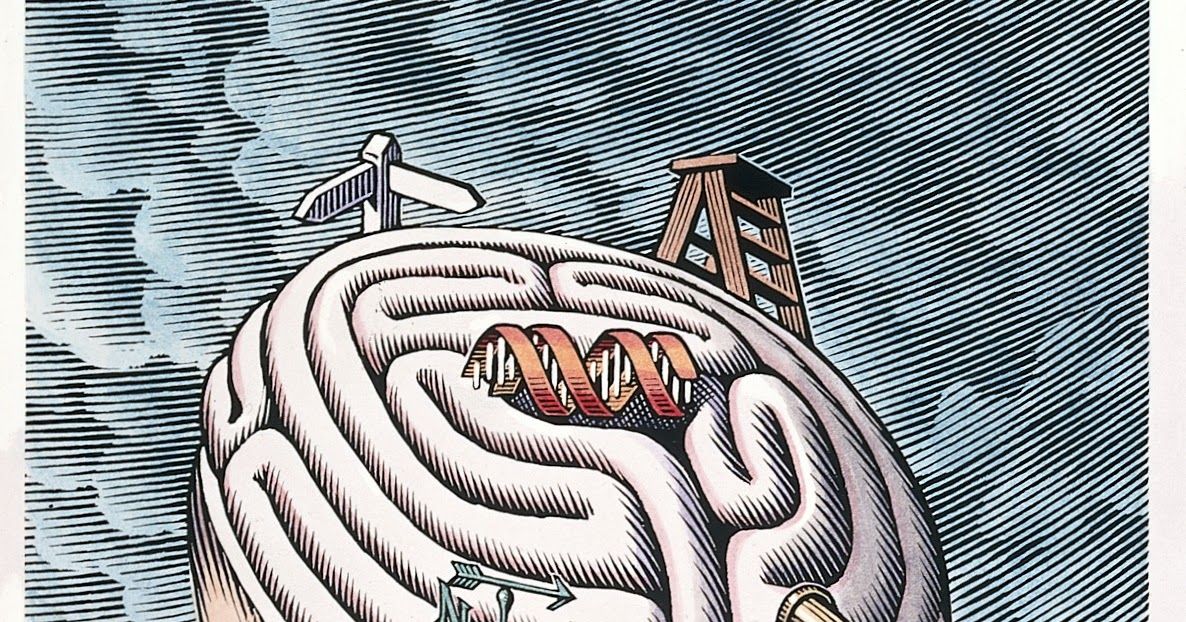

Since his days as a teacher at Stanford University, Fossel has studied aging from a medical and scientific perspective with a particular emphasis on premature aging syndromes such as progeria, and since at least 1996 he has been a strong and vocal advocate of [telomerase therapy]] as a potential treatment of age-related diseases, disorders, and syndromes such as progeria, Alzheimer’s disease, atherosclerosis, osteoporosis, cancer, and other conditions. However, he is careful to qualify his advocacy of telomerase therapy as being a potential treatment for these conditions rather than a “cure for old age” and a panacea for age-related medical conditions, albeit a potential treatment that could radically extend the maximum human life span and reverse the aging process in most people. Specifically, Fossel sees the potential of telomerase therapy as being the single most effective point of intervention in a wide variety of age-related medical conditions. His new book, The Telomerase Revolution, (BenBella, 2015) gives a careful explanation of aging, age-related diseases, and the prospects for intervention, including upcoming human trials.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/agingreversed

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Aging_Reversed

Support the Channel: https://goo.gl/ciSpg1

Channel t-shirt: https://teespring.com/aging-reversed

Read more