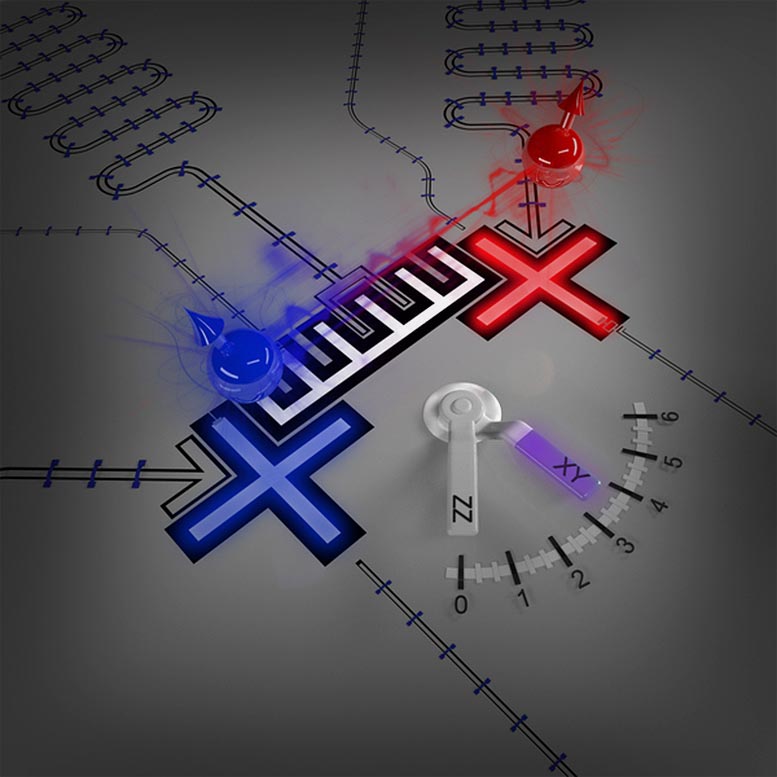

Why can atoms or elementary particles behave like waves according to quantum physics, which allows them to be in several places at the same time? And why does everything we see around us obviously obey the laws of classical physics, where that is impossible? To answer those questions, in recent years researchers have coaxed larger and larger objects into behaving quantum mechanically. One consequence of this is that, when passing through a double slit, they form an interference pattern that is characteristic of waves.

Up to now this could be achieved with molecules consisting of a few thousand atoms. However, physicists hope one day to be able to observe such quantum effects with properly macroscopic objects. Lukas Novotny, Professor of Photonics, and his collaborators at the Department of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering at ETH Zurich have now made a crucial step in that direction. Their results were recently published in the scientific journal Nature.

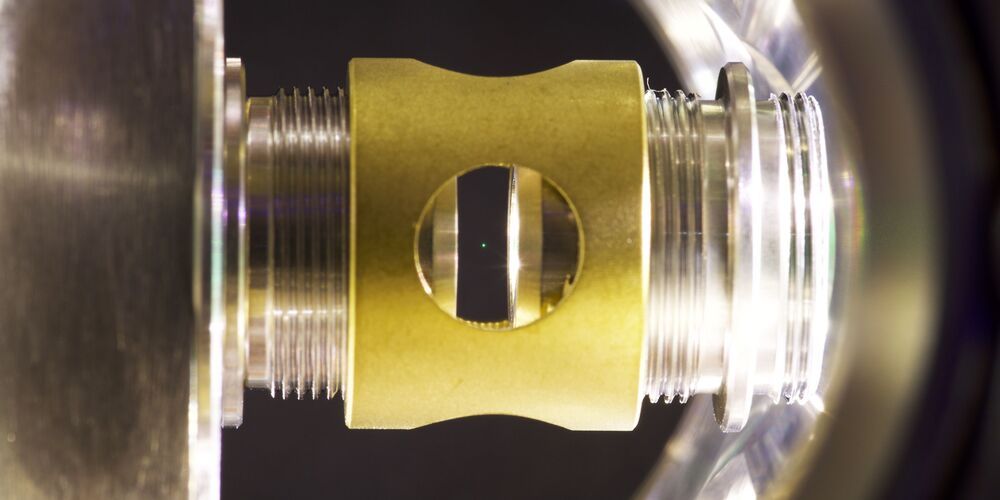

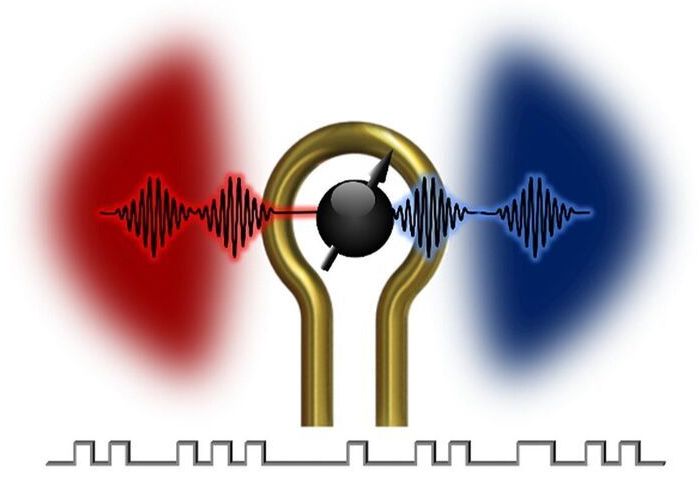

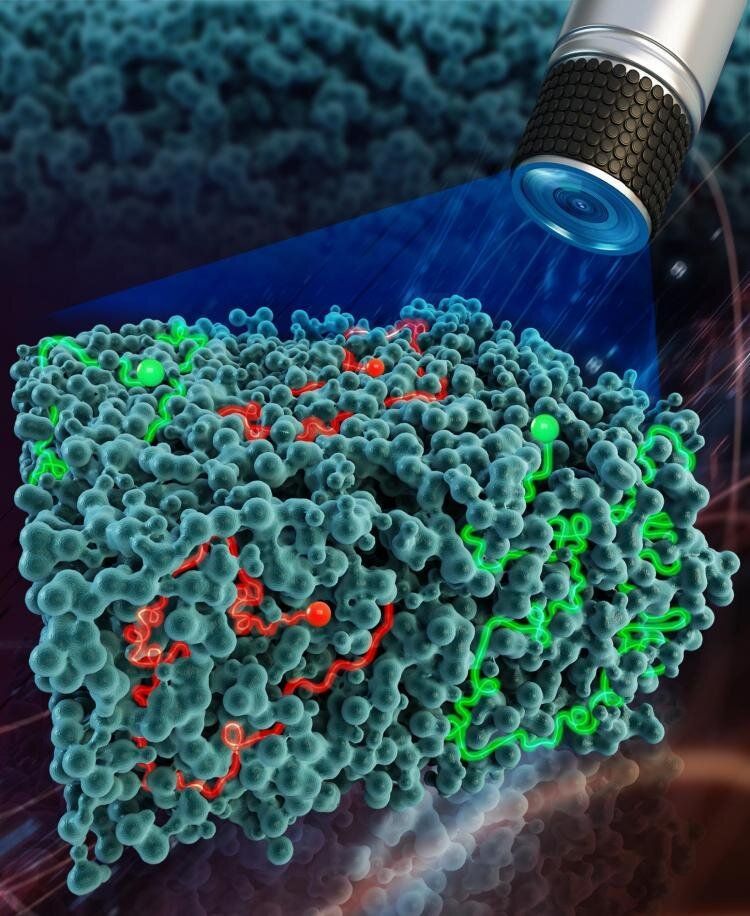

Researchers at ETH Zurich have trapped a tiny sphere measuring a hundred nanometres using laser light and slowed down its motion to the lowest quantum mechanical state. Based on this, one can study quantum effects in macroscopic objects and build extremely sensitive sensors.