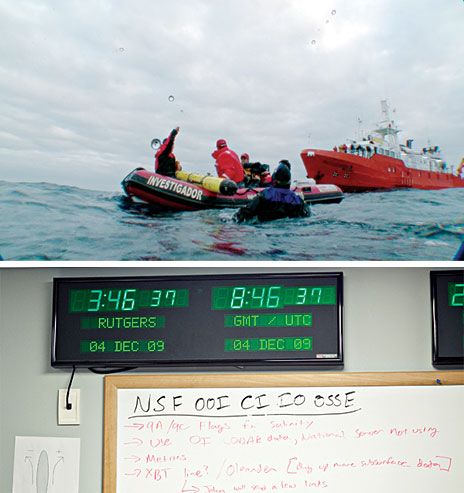

Circa 2010

About 48 kilometers off the eastern coast of the United States, scientists from Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, peered over the side of a small research vessel, the Arabella. They had just launched RU27, a 2-meter-long oceanographic probe shaped like a torpedo with wings. Although it sported a bright yellow paint job for good visibility, it was unclear whether anyone would ever see this underwater robot again. Its mission, simply put, was to cross the Atlantic before its batteries gave out.

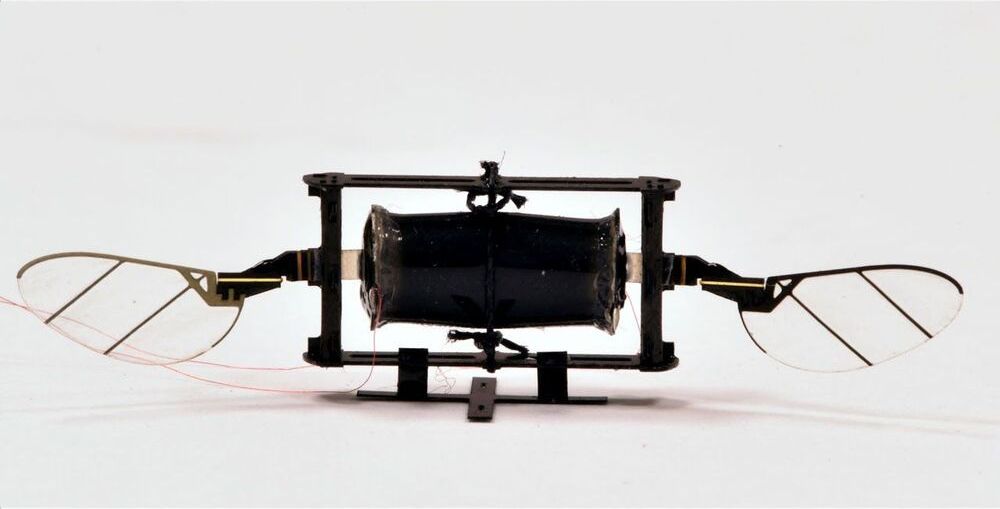

Unlike other underwater drones, RU27 and its kin are able to travel without the aid of a propeller. Instead, they move up and down through the top 100 to 200 meters of seawater by adjusting their buoyancy while gliding forward using their swept-back wings. With this strategy, they can go a remarkably long way on a remarkably small amount of energy.

When submerged and thus out of radio contact, RU27 steered itself with the aid of sensors that registered depth, heading, and angle from the horizontal. From those inputs, it could dead reckon about where it had glided since its last GPS navigational fix: Every 8 hours the probe broke the surface and briefly stuck its tail in the air, which exposed its GPS antenna as well as the antenna of an Iridium satellite modem. This allowed the vehicle to contact its operators, who were located in New Brunswick, N.J., in the Rutgers Coastal Ocean Observation Lab, or COOL Room.