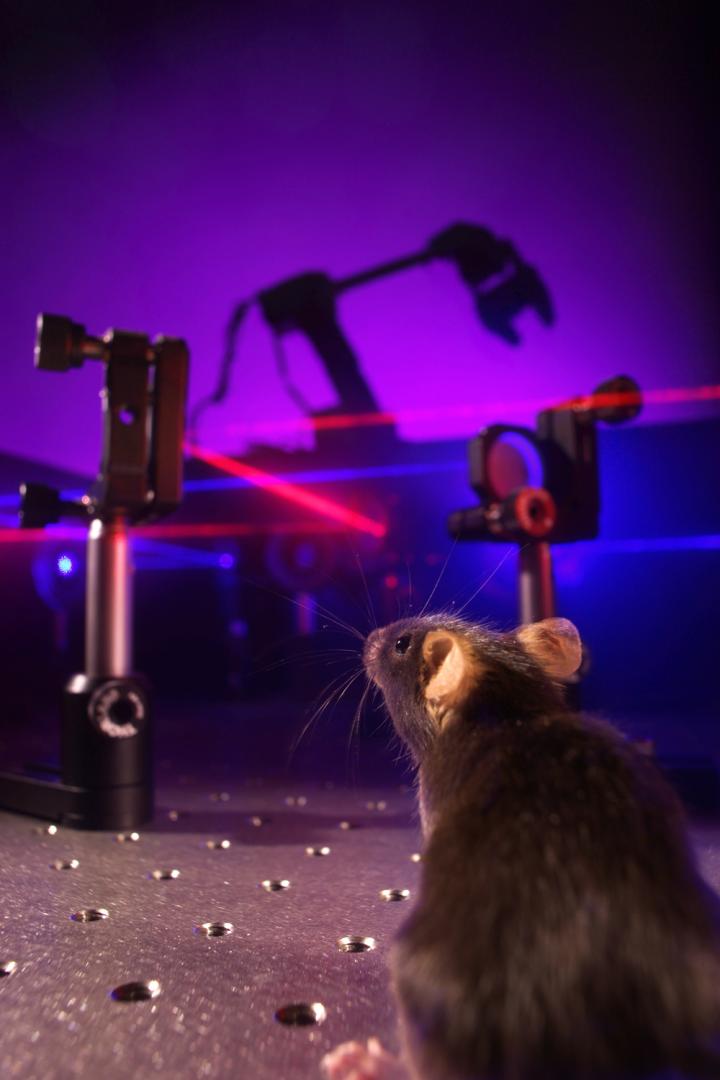

A new well written but not very favorable write-up on #transhumanism. Despite this, more and more publications are tackling describing the movement and its science. My work is featured a bit.

On the eve of the 20th century, an obscure Russian man who had refused to publish any of his works began to finalize his ideas about resurrecting the dead and living forever. A friend of Leo Tolstoy’s, this enigmatic Russian, whose name was Nikolai Fyodorovich Fyodorov, had grand ideas about not only how to reanimate the dead but about the ethics of doing so, as well as about the moral and religious consequences of living outside of Death’s shadow. He was animated by a utopian desire: to unite all of humanity and to create a biblical paradise on Earth, where we would live on, spurred on by love. He was an immortalist: one who desired to conquer death through scientific means.

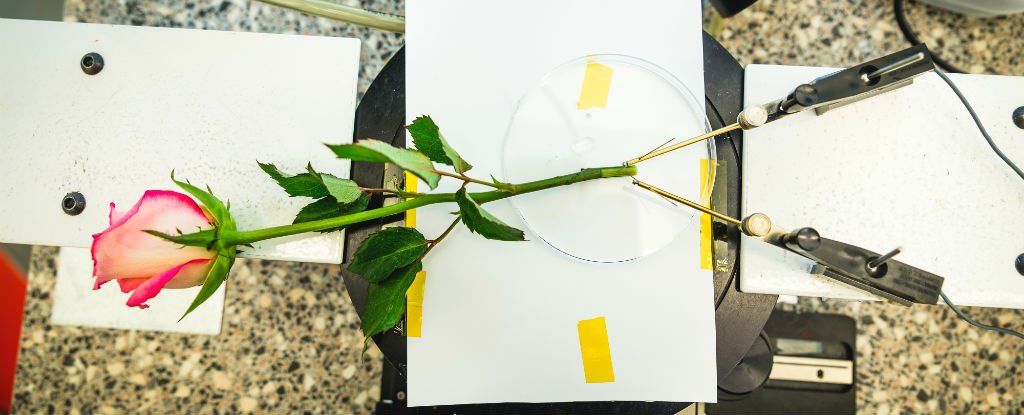

Despite the religious zeal of his notions—which a number of later Christian philosophers unsurprisingly deemed blasphemy—Fyodorov’s ideas were underpinned by a faith in something material: the ability of humans to redevelop and redefine themselves through science, eventually becoming so powerfully modified that they would defeat death itself. Unfortunately for him, Fyodorov—who had worked as a librarian, then later in the archives of Ministry of Foreign Affairs—did not live to see his project enacted, as he died in 1903.

Fyodorov may be classified as an early transhumanist. Transhumanism is, broadly, a set of ideas about how to technologically refine and redesign humans, such that we will eventually be able to escape death itself. This desire to live forever is strongly tied to human history and art; indeed, what may be the earliest of all epics, the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, portrays a character who seeks a sacred plant in the black depths of the sea that will grant him immortality. Today, however, immortality is the stuff of religions and transhumanism, and how these two are different is not always clear to outsiders.

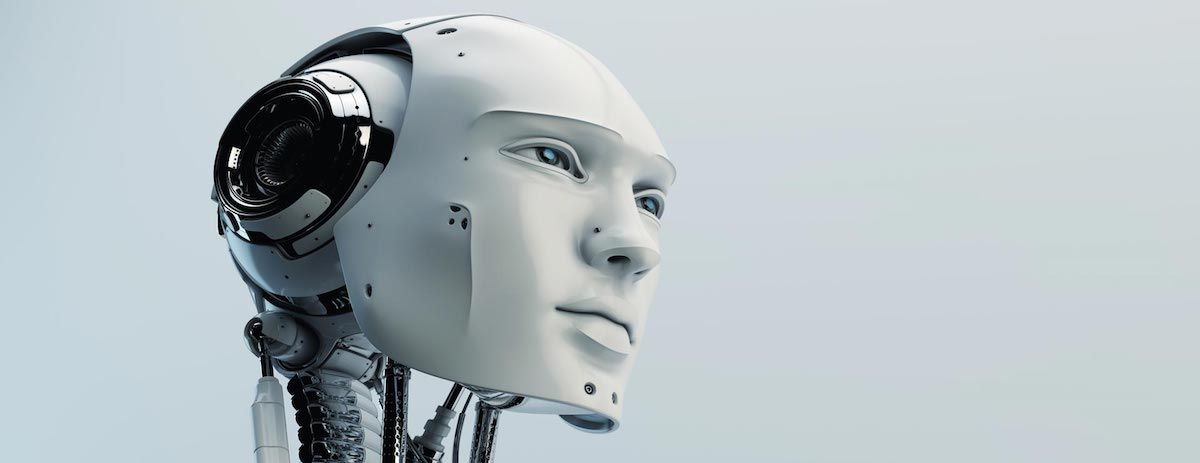

Contemporary schemes to beat death usually entail being able to “upload” our minds into computers, then downloading our minds into new, better bodies, cyborg or robot bodies immune to the weaknesses that so often define us in our current prisons of mere flesh and blood. The transhumanist movement—which is many movements under one umbrella—is understandably controversial; in 2004 in a special issue of Foreign Policy devoted to deadly ideas, Francis Fukuyama famously dubbed transhumanism one of the most dangerous ideas in human history. And many, myself included, have a natural tendency to feel a kind of alienation from, if not repulsion towards, the idea of having our bodies—after our hearts stop—flushed free of blood and filled with cryonic nitrogen, suspending us, supposedly, until our minds can be uploaded into a new, likely robotic, body—one harder, better, and faster, as Daft Punk might have put it.

Read more