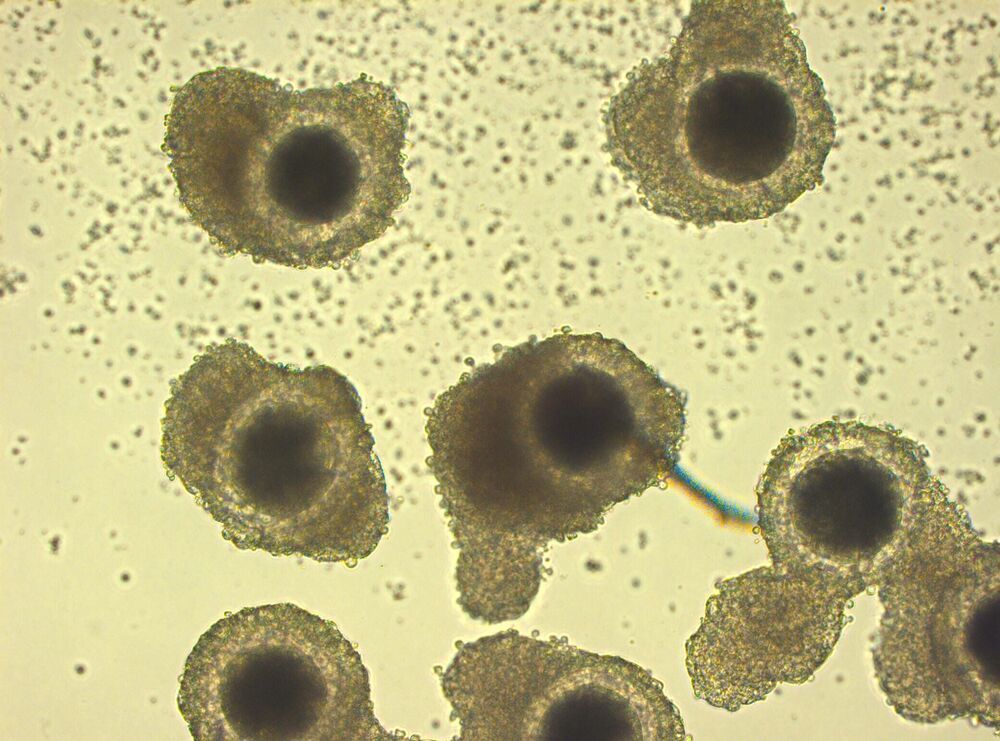

The resulting implant consists of cells attached to the scaffold, which permits the targeted delivery of therapeutic cells to the diseased region within the eye. A non-cryopreserved formulation of this cellular therapy is being employed in an ongoing Phase I/IIa clinical trial sponsored by RPT. The cryopreserved formulation enabled by the work of Pennington and colleagues will facilitate anticipated Phase IIb and Phase III clinical trials as well as ultimate commercialization and clinical application of the product.

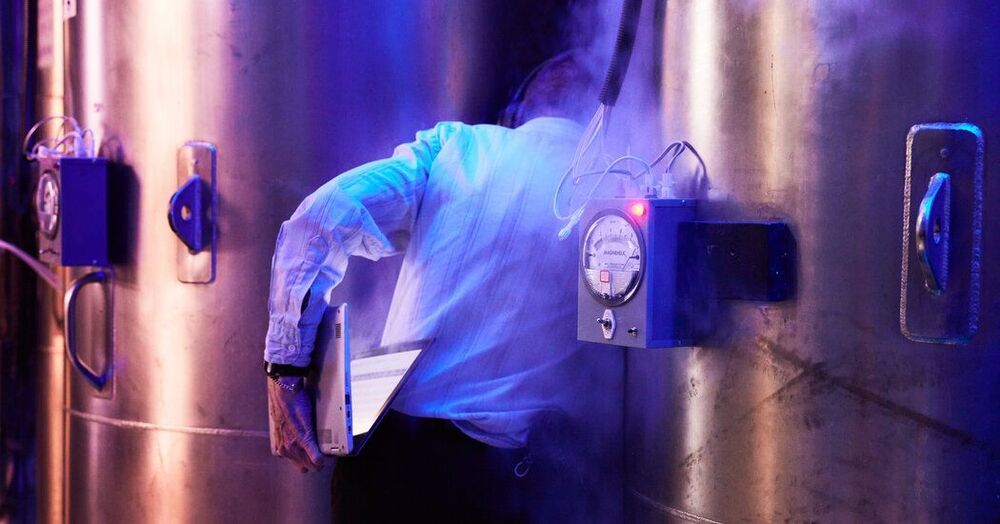

Scientists at UC Santa Barbara, University of Southern California (USC), and the biotechnology company Regenerative Patch Technologies LLC (RPT) have reported new methodology for preservation of RPT’s stem cell-based therapy for age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

The new research, recently published in Scientific Reports, optimizes the conditions to cryopreserve, or freeze, an implant consisting of a single layer of ocular cells generated from human embryonic stem cells supported by a flexible scaffold about 3×6 mm in size. This implant is currently in clinical trial for the treatment of AMD, the leading cause of blindness in aging populations. The results demonstrate that the implant can be frozen, stored for long periods and distributed in frozen form to clinical sites where it is designed to be thawed and immediately implanted into the eyes of patients with macular degeneration. The capacity to cryopreserve this and other cell-based therapeutics will extend shelf life and enable on-demand distribution to distant clinical sites, increasing the number of patients able to benefit from such treatments.

The report published by lead author Britney Pennington and colleagues achieves a milestone that brings ocular implants one step closer to the clinic. “This is the first published report that demonstrates high viability and function of adherent ocular cells following cryopreservation, even after long-term frozen storage,” said Pennington, head of process development at RPT and assistant project scientist at UC Santa Barbara.