An Earth-sized telescope will capture the unseeable.

Wormholes, or hypothetical tunnels through space-time that allow faster-than-light travel, could potentially leave dark, telltale imprints in the sky that might be seen with telescopes, a new study suggests.

These slightly bent, oblong wormhole “shadows” could be distinguished from the more circular patches left by black holes and, if detected, could show that the cosmic shortcuts first proposed by Albert Einstein more than a century ago are, in fact, real, one researcher says.

Wormholes are cosmic shortcuts, tunnels burrowing through hyperspace. Hop in one end, and you could emerge on the other side of the universe — a convenient method of hyperfast travel that’s become a trope of science fiction. [8 Ways You Can See Einstein’s Theory of Relativity in Real Life].

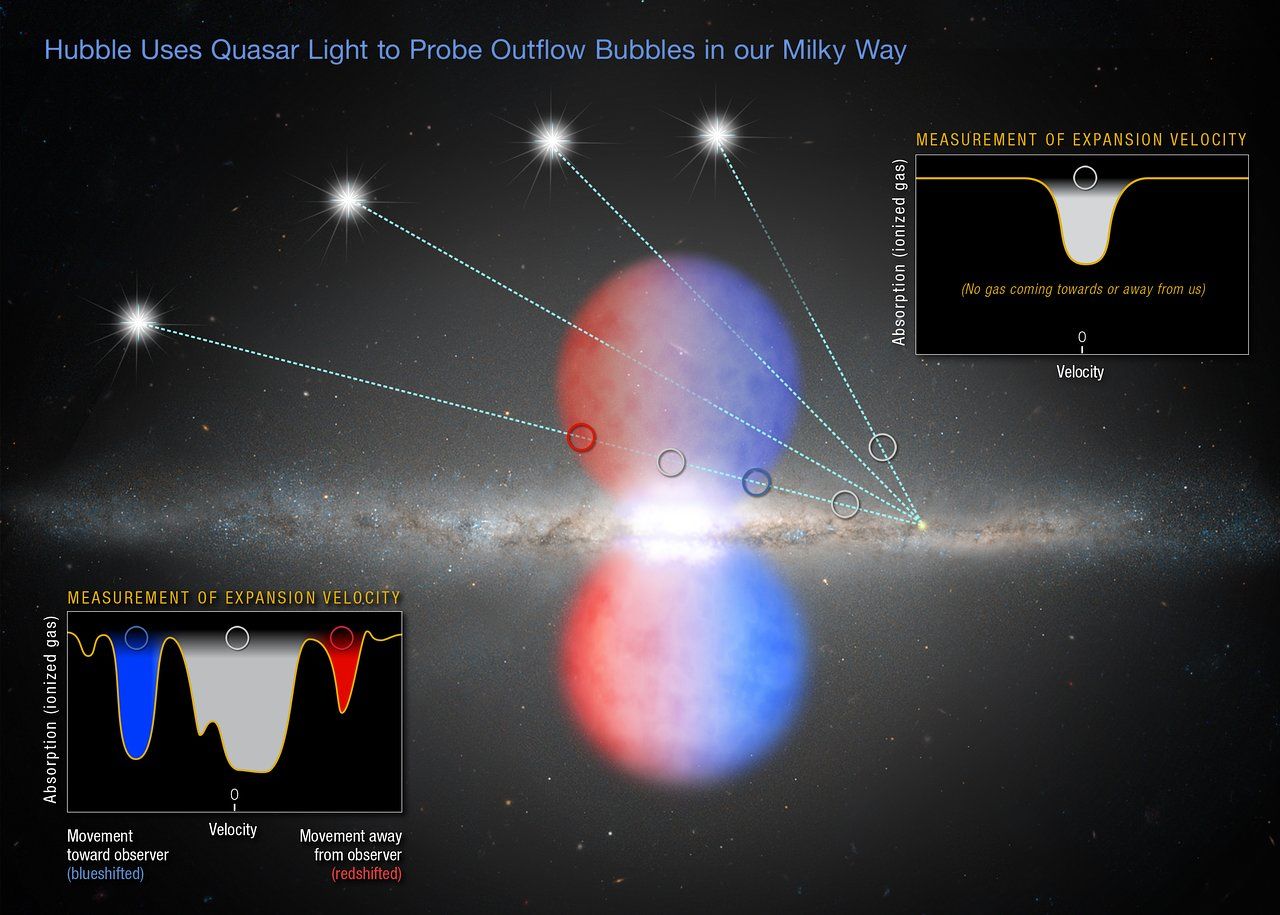

This artist’s impression shows the light of several distant quasars piercing the northern half of the Fermi Bubbles, an outflow of gas expelled by the supermassive black hole in the centre of the Milky Way. The NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope probed the quasars’ light for information on the speed of the gas and whether the gas is moving toward or away from Earth. Based on the material’s speed, the research team estimated that the bubbles formed from an energetic event between 6 million and 9 million years ago.

The inset diagram at bottom left shows the measurement of gas moving toward and away from Earth, indicating the material is traveling at a high velocity.

Hubble also observed light from quasars that passed outside the northern bubble. The box at upper right reveals that the gas in one such quasar’s light path is not moving toward or away from Earth. This gas is in the disc of the Milky Way and does not share the same characteristics as the material probed inside the bubble.

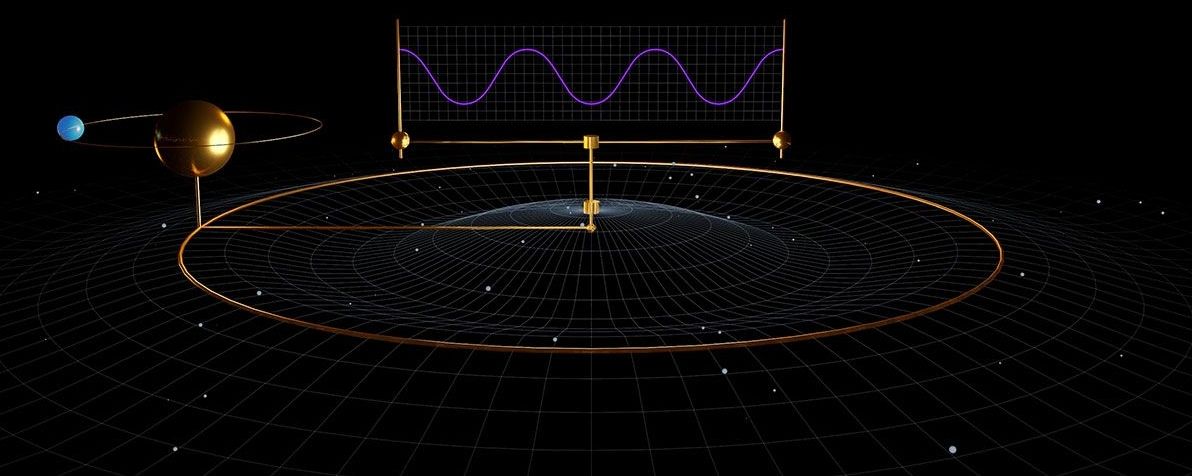

COLUMBUS, Ohio — A gravitational wave detector that’s 2.5 miles long isn’t cool. You know what’s cool? A 25-mile-long gravitational wave detector.

That’s the upshot of a series of talks given here Saturday (April 14) at the April meeting of the American Physical Society. The next generation of gravitational wave detectors will peer right up to the outer edge of the observable universe, looking for ripples in the very fabric of space-time, which Einstein predicted would occur when massive objects like black holes collide. But there are still some significant challenges standing in the way of their construction, presenters told the audience.

“The current detectors you might think are very sensitive,” Matthew Evans, a physicist at MIT, told the audience. “And that’s true, but they’re also the least sensitive detectors with which you can [possibly] detect gravitational waves.” [8 Ways You Can See Einstein’s Theory of Relativity in Real Life].