Cranmer is a member of ATLAS, one of the two general-purpose experiments that, among other things, co-discovered the Higgs boson at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN. He and other CERN researchers recently published a letter in Nature Physics titled “Open is not enough,” which shares lessons learned about providing open data in high-energy physics. The CERN Open Data Portal, which facilitates public access of datasets from CERN experiments, now contains more than two petabytes of information.

It could be said that astronomy, one of the oldest sciences, was one of the first fields to have open data. The open records of Chinese astronomers from 1054 A.D. allowed astronomer Carlo Otto Lampland to identify the Crab Nebula as the remnant of a supernova in 1921. In 1705 Edward Halley used the previous observations of Johannes Kepler and Petrus Apianus—who did their work before Halley was old enough to use a telescope—to deduce the orbit of his eponymous comet.

In science, making data open means making available, free of charge, the observations or other information collected in a scientific study for the purpose of allowing other researchers to examine it for themselves, either to verify it or to conduct new analyses.

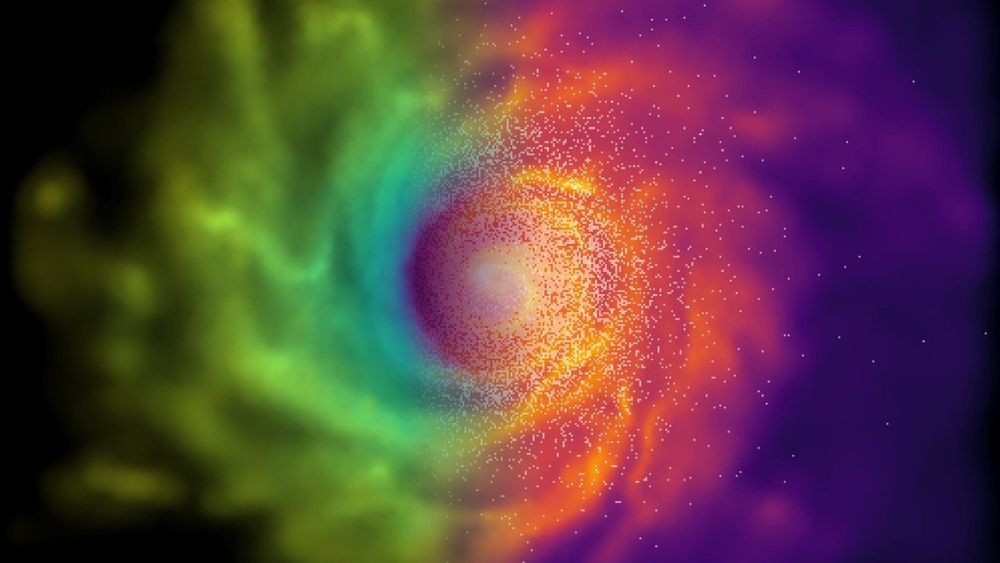

Scientists continue to use open data to make new discoveries today. In 2010, a team of scientists led by Professor Doug Finkbeiner at Harvard University found vast gamma-ray bubbles above and below the Milky Way. The accomplishment was compared to the discovery of a new continent on Earth. The scientists didn’t find the bubbles by making their own observations; they did it by analyzing publicly available data from the Fermi Gamma Ray Telescope.