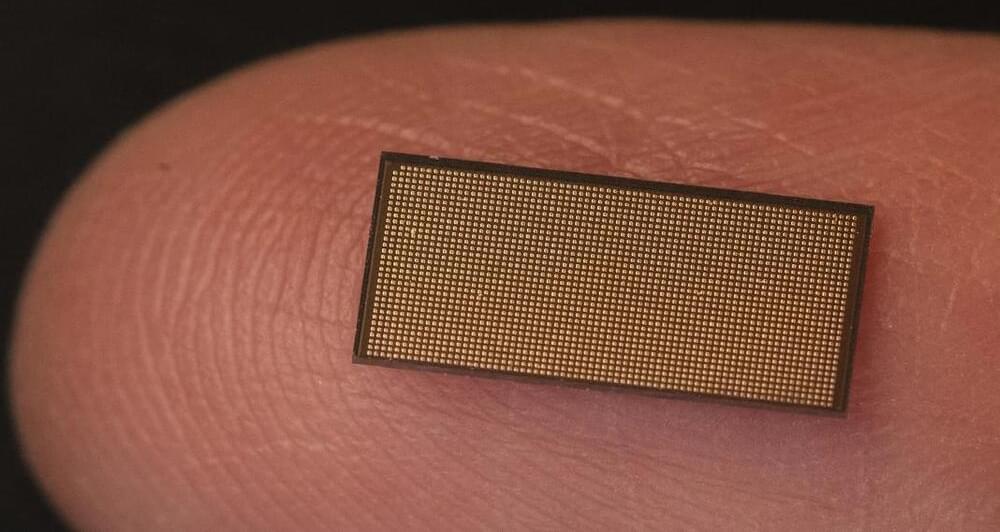

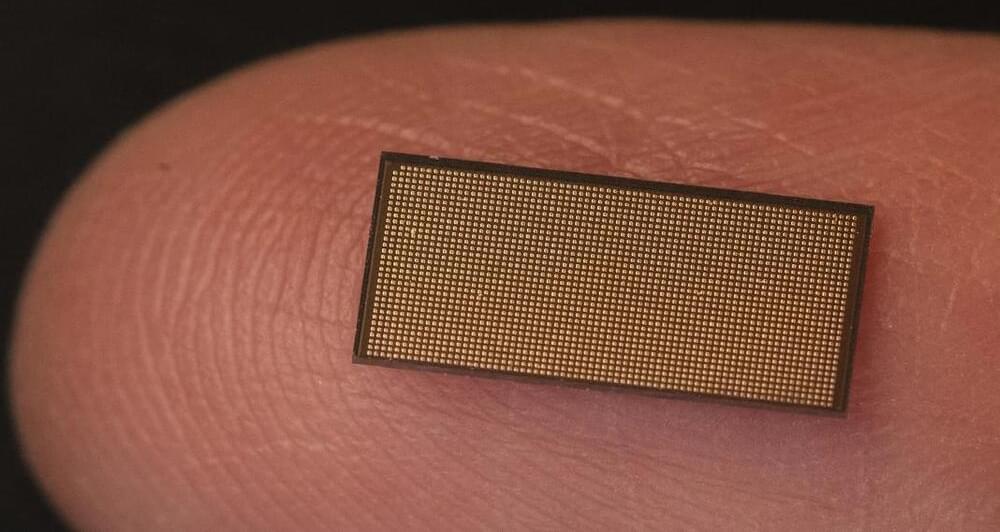

The Loihi 2 chip doesn’t just significantly boost the number of neurons from its first iteration, it also greatly expands their functionality.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=YYgG2a-_2po

We all know glass comes from sand but we don’t always get to see this process in action. In this video, we bring you footage of a solar-powered 3D printer that makes glass sculptures out of sand. Impressed? Just wait till you see the clips.

The 3D printer is called Solar Sinter and it was built by Markus Kayser. It works in the following way: after computer-drawn models are loaded into the machine, a large Fresnel lens beams sunlight onto a sandbox which leads to high temperatures of 2,552–2,912 F (1,400–1,600 C).

This extreme heat allows the sand to melt and become malleable enough to be molded into beautiful glass sculptures. The machine was first put to the test in the Sahara Desert. You can guess that the desert’s conditions allowed the 3D printer to perform to perfection.

DETROIT — General Motors on Friday said it expects to reopen the remaining three North American assembly plants that have been idled because of the global microchip shortage by Nov. 1.

GM also said it plans to resume building Chevrolet Malibu sedans for the first time in nearly nine months at a plant that has partially reopened in Kansas.

The automaker said its plant in Ramos Arizpe, Mexico, which has been shut since mid-August, would start building Chevy Blazers on Oct. 18 followed by Chevy Equinoxes as soon as Nov. 1.

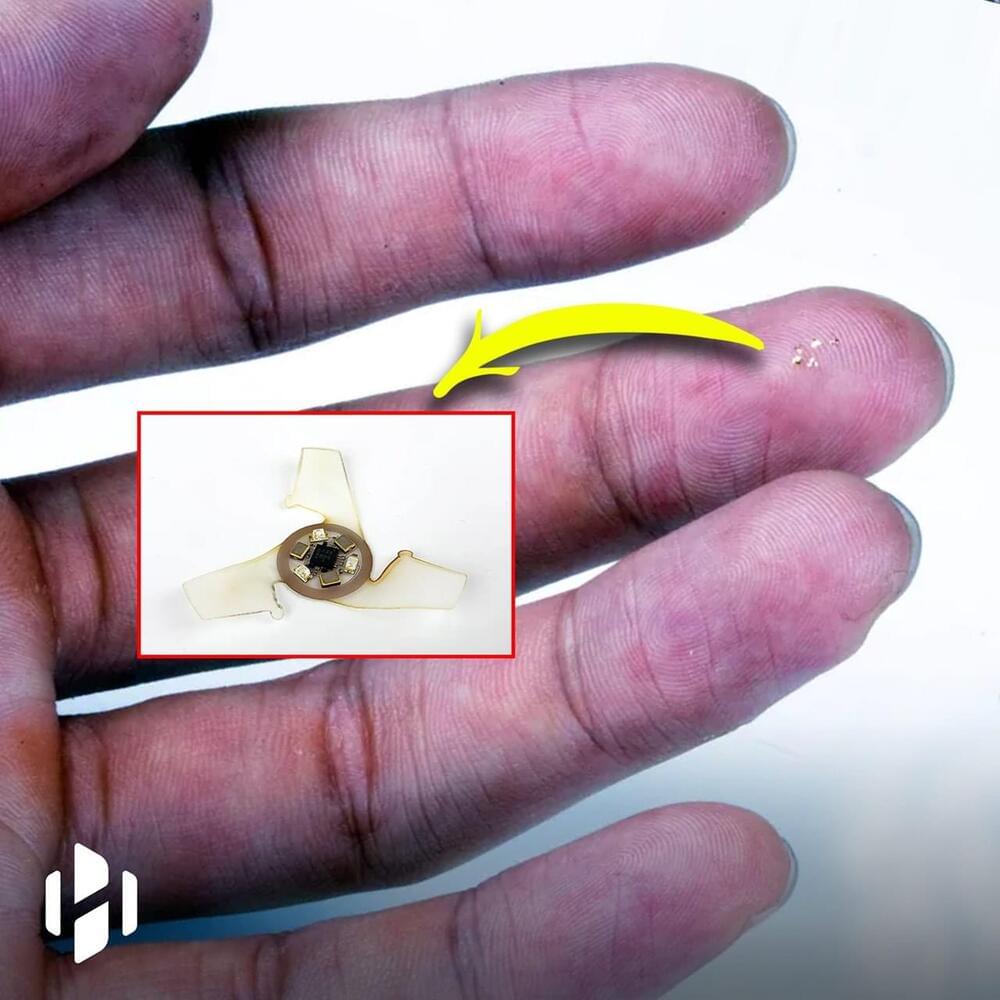

The semiconductor shortage has curtailed the choices available to designers and caused some inventive solutions to be found, but the one used by [djzc] is probably the most inventive we’ve yet seen. The footprint trap, when a board is designed for one footprint but shortages mean the part is only available in another, has caught out many an engineer this year. In this case an FTDI chip had been designed with a PCB footprint for a QFN package when the only chip to be found was a QFP from a breakout board.

For those unfamiliar with semiconductor packaging, a QFN and QFP share a very similar epoxy package, but the QFN has its pins on the underside flush with the epoxy and the QFP has them splayed out sideways. A QFP is relatively straightforward to hand-solder so it’s likely we’ll have seen more of them than QFNs on these pages.

There is no chance for a QFP to be soldered directly to a QFN footprint, so what’s to be done? The solution is an extremely inventive one, a two-PCB sandwich bridging the two. A lower PCB is made of thick material and mirrors the QFN footprint above the level of the surrounding components, while the upper one has the QFN on its lower side and a QFP on its upper. When they are joined together they form an inverted top-hat structure with a QFN footprint below and a QFP footprint on top. Difficult to solder in place, but the result is a QFP footprint to which the chip can be attached. We like it, it’s much more elegant than elite dead-bug soldering!

Taiwan’s TSMC and Japan’s Sony Group Corp are considering jointly building a chip factory in Japan, with the government ready to pay for some of the investment of about 800 billion yen ($7.15 billion), the Nikkei reported on Friday, October 8 2021. (

WORLD’S LARGEST CHIPMAKER TO RAISE PRICES, THREATENING COSTLIER ELECTRONICS

Both Sony and TSMC declined to comment. But TSMC, the world’s largest contract chipmaker and major Apple Inc supplier had said in July that it was reviewing a plan to set up production in Japan.

In a rare non-magnetic kagome material, a topological metal cools into a superconductor through a sequence of novel charge density waves. Researchers have discovered a complex landscape of electronic states that can co-exist on a kagome lattice, resembling those in high-temperature superconductor.

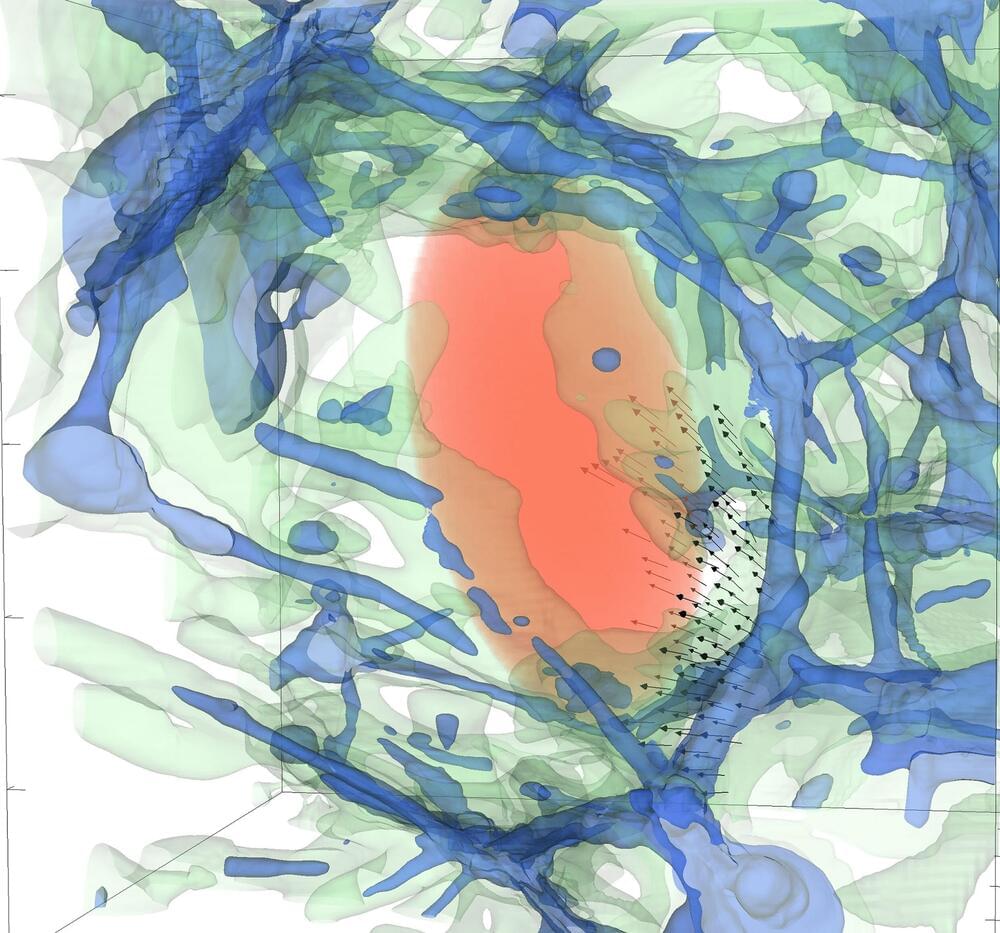

The Computational Cosmology group of the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics (DAA) of Valencia University (UV) has published an article in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, one of the international journals with the greatest impact in Astrophysics, which shows, with complex theoretical-computational models, that cosmic voids are constantly replenished with external matter.

The Computational Cosmology group of the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics (DAA) of Valencia University (UV) has published an article in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, one of the international journals with the greatest impact in Astrophysics, which shows, with complex theoretical-computational models, that cosmic voids are constantly replenished with external matter.

“This totally unexpected result can have transcendental implications, not only for our understanding of the large-scale structure of the universe, but on the settings for the creation and evolution of galaxies,” explains Vicente Quilis, director at the DAA and head researcher for the project.

“Cosmic voids are the largest structures in the cosmos, and knowledge on their creation and evolution is essential to understand the structure of the universe,” says Susana Planelles, co-director of the research. Studying them as a physical occurrence has always been extremely complex precisely due to being large volumes with very low material content. From an observational point of view, analyzing the few existing items inside them is very hard, and the theoretical modeling of these occurrences is no less complex, which is why highly simplified descriptions of these structures are used.

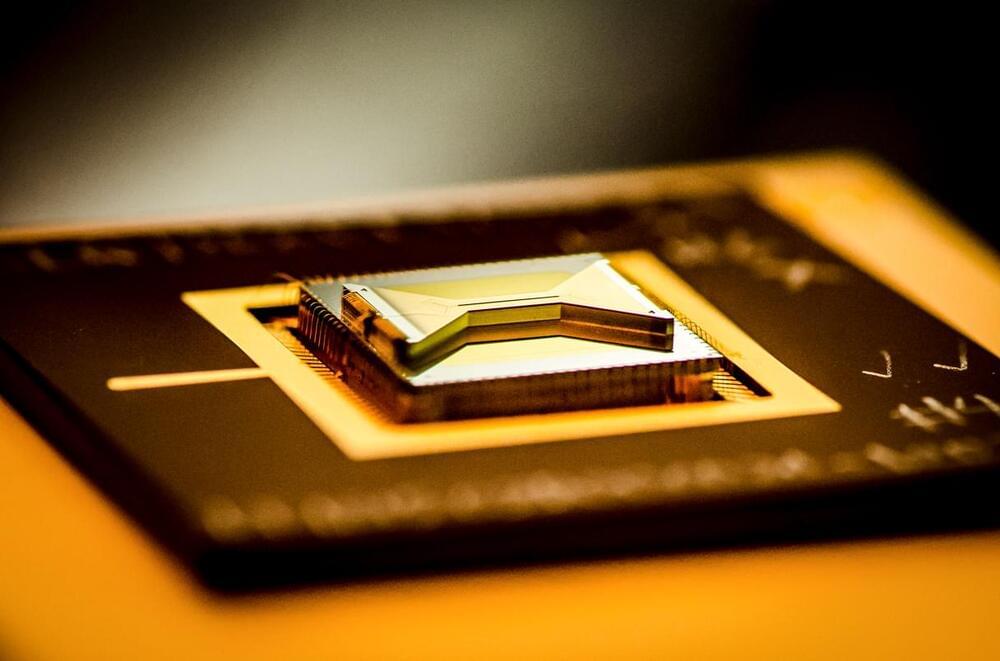

Most important, the encoded logical qubit performed better than the physical ones on which it depends, at least in some ways. For example, the researchers succeeded in preparing either the logical 0 or the logical 1 state 99.67% of the time—better than the 99.54% for the individual qubits. “This is really the first time that the quality of the [logical] qubit is better than the components that encode it,” says Monroe, who is cofounder of IonQ, a company developing ion-based quantum computers.

However, Egan notes, the encoded qubit did not outshine the individual ions in every way. Instead, he says, the real advance is in demonstrating fault tolerance, which means the error-correcting machinery works in a way that doesn’t introduce more errors than it corrects. “Fault tolerance is really the design principle that prevents errors from spreading,” says Egan, now at IonQ.

Martinis questions that use of the term, however. To claim true fault-tolerant error correction, he says, researchers must do two other things. They must show that the errors in a logical qubit get exponentially smaller as the number of physical qubits increases. And they must show they can measure the ancillary qubits repeatedly to maintain the logical qubit, he says.