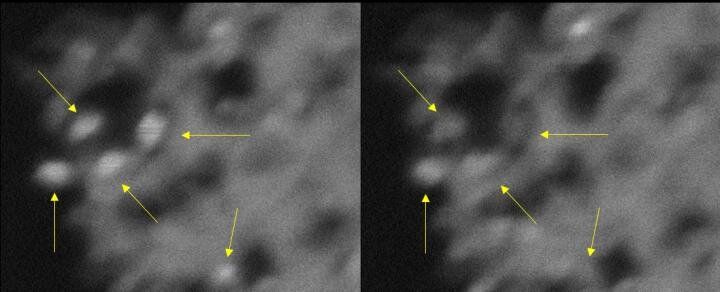

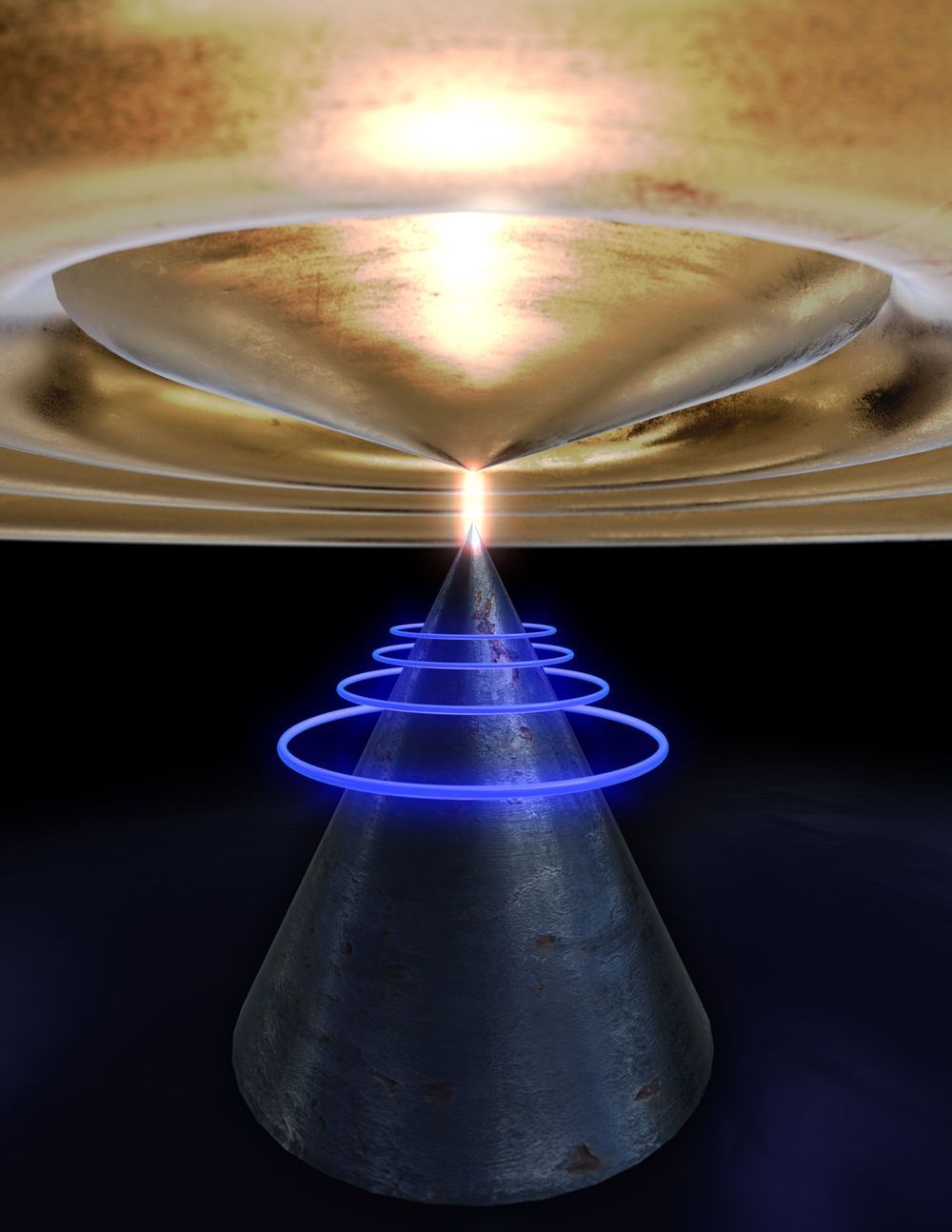

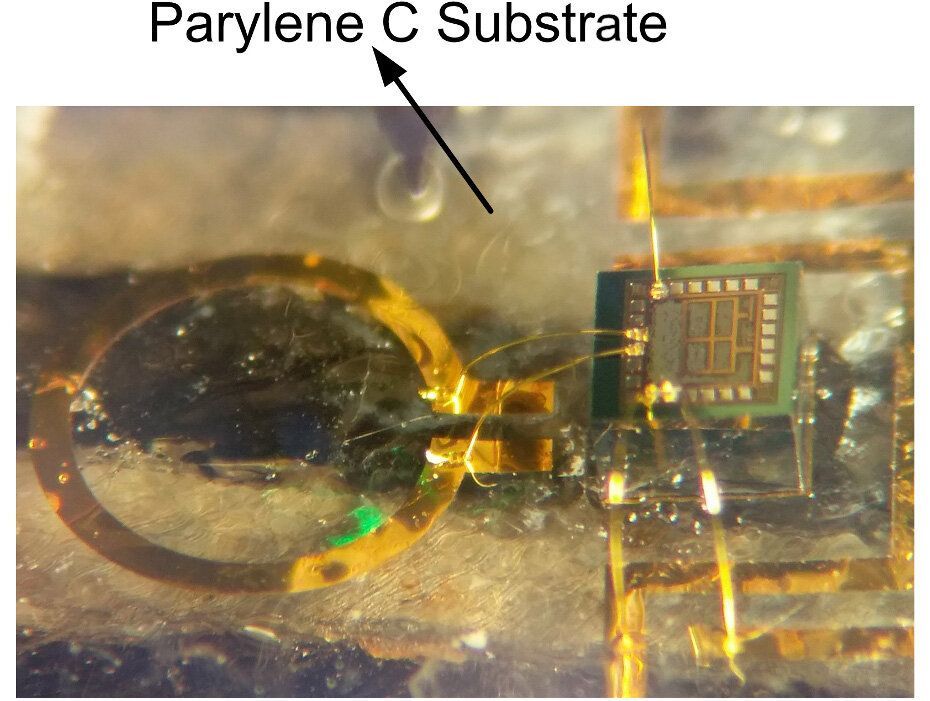

In research published in Science Advances, a group led by scientists from the RIKEN Center for Emergent Matter Science (CEMS) have used the principle of magneto-rotation coupling to suppress the transmission of sound waves on the surface of a film in one direction while allowing them to travel in the other. This could lead to the development of acoustic rectifiers—devices that allow waves to propagate preferentially in one direction, with potential applications in communications technology.

Devices known as rectifiers are extremely important in technology development. The best known are electronic diodes, which are used to convert AC into DC electricity, essentially making electrification possible.

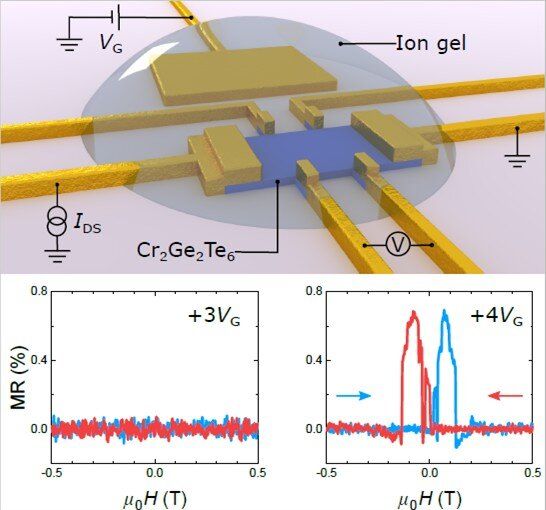

In the current study, the group examined the movement of acoustic surface waves—movements of sound like the propagation of earthquakes over the surface of the Earth—in a magnetic film. There is interplay between the surface acoustic waves and spin waves, disturbances in magnetic fields within the material that can move through the material.