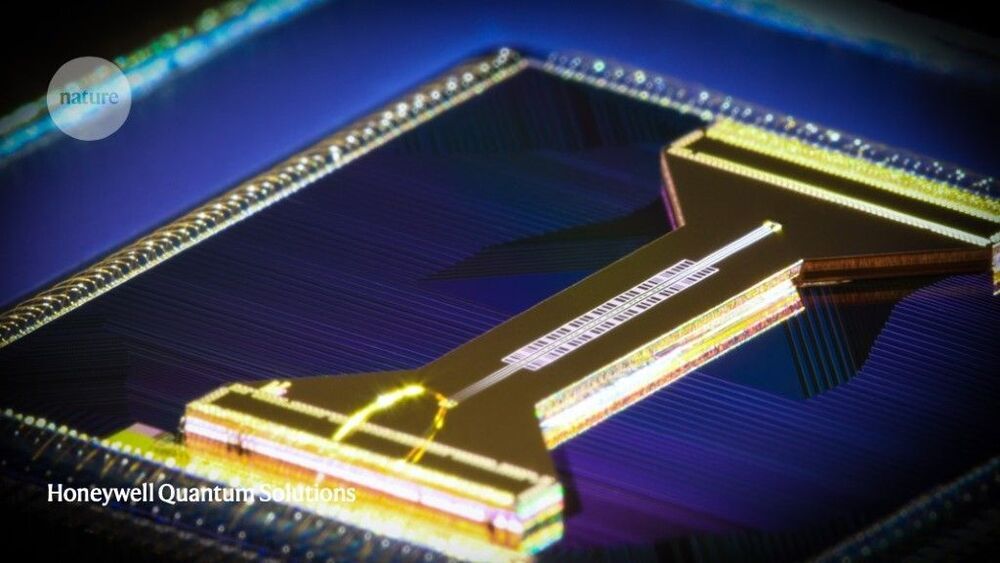

This discovery opens the door to topological quantum computing. Current quantum computing systems, where the elemental units of calculation are qubits that perform superfast calculations, require superconducting materials that only function in extremely cold conditions. Fluctuations in heat can throw one of these systems out of whack.

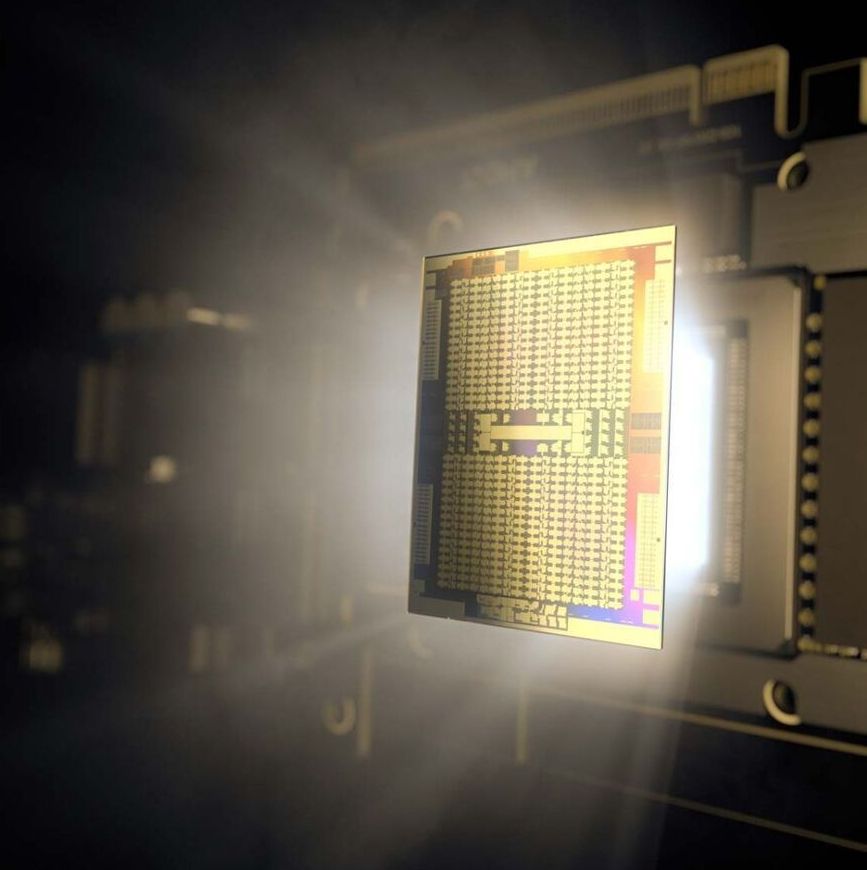

“The properties inherent to materials such as TaP could form the basis of future qubits,” says Nguyen. He envisions synthesizing TaP and other topological semimetals — a process involving the delicate cultivation of these crystalline structures — and then characterizing their structural and excitational properties with the help of neutron and X-ray beam technology, which probe these materials at the atomic level. This would enable him to identify and deploy the right materials for specific applications.

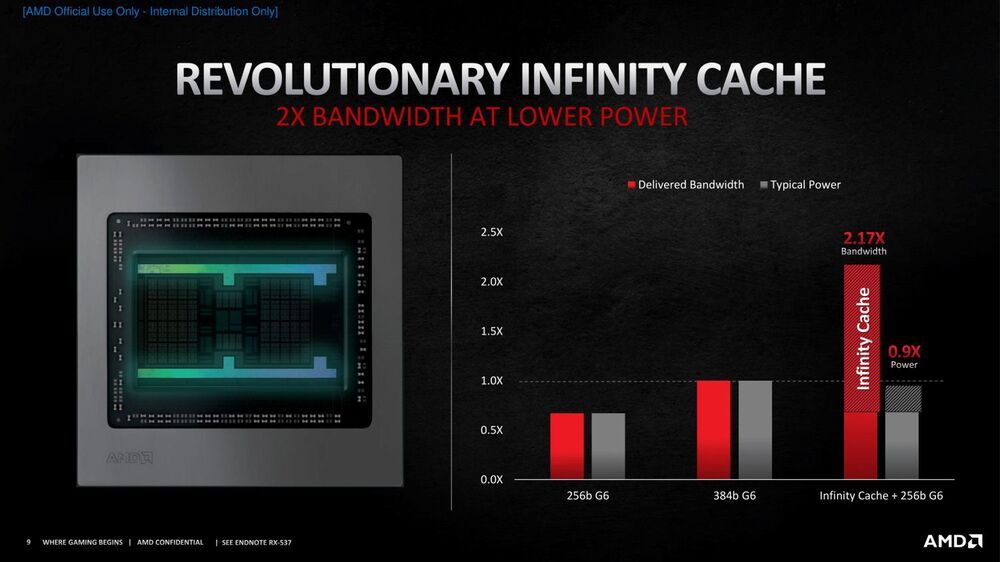

“My goal is to create programmable artificial structured topological materials, which can directly be applied as a quantum computer,” says Nguyen. “With infinitely better heat management, these quantum computing systems and devices could prove to be incredibly energy efficient.”