Searching for new substances and developing new techniques in the chemical industry: tasks that are often accelerated using computer simulations of molecules or reactions. But even supercomputers quickly reach their limits. Now researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics in Garching (MPQ) have developed an alternative, analogue approach. An international team around Javier Argüello-Luengo, Ph.D. candidate at the Institute of Photonic Sciences (ICFO), Ignacio Cirac, Director and Head of the Theory Department at the MPQ, Peter Zoller, Director at the Institute of Quantum Optics and Quantum Information in Innsbruck (IQOQI), and others have designed the first blueprint for a quantum simulator that mimics the quantum chemistry of molecules. Like an architectural model can be used to test the statics of a future building, a molecule simulator can support investigating the properties of molecules. The results are now published in the scientific journal Nature.

Using hydrogen, the simplest of all molecules, as an example, the global team of physicists from Garching, Barcelona, Madrid, Beijing and Innsbruck theoretically demonstrate that the quantum simulator can reproduce the behaviour of a real molecule’s electron shell. In their work, they also show how experimental physicists can build such a simulator step by step. “Our results offer a new approach to the investigation of phenomena appearing in quantum chemistry,” says Javier Argüello-Luengo. This is highly interesting for chemists because classical computers notoriously struggle to simulate chemical compounds, as molecules obey the laws of quantum physics. An electron in its shell, for example, can rotate to the left and right simultaneously. In a compound of many particles, such as a molecule, the number of these parallel possibilities multiplies. Because each electron interacts with each other, the complexity quickly becomes impossible to handle.

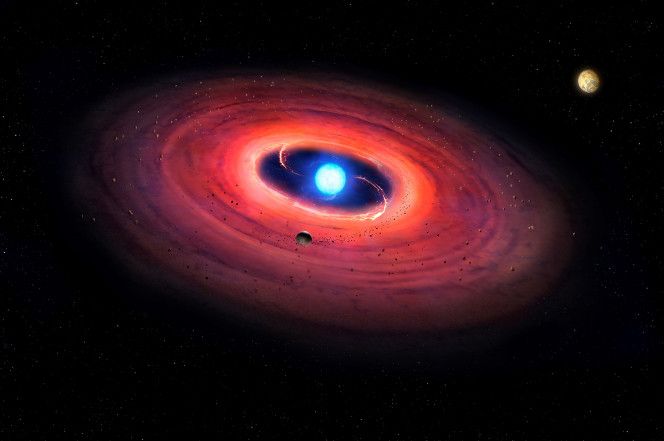

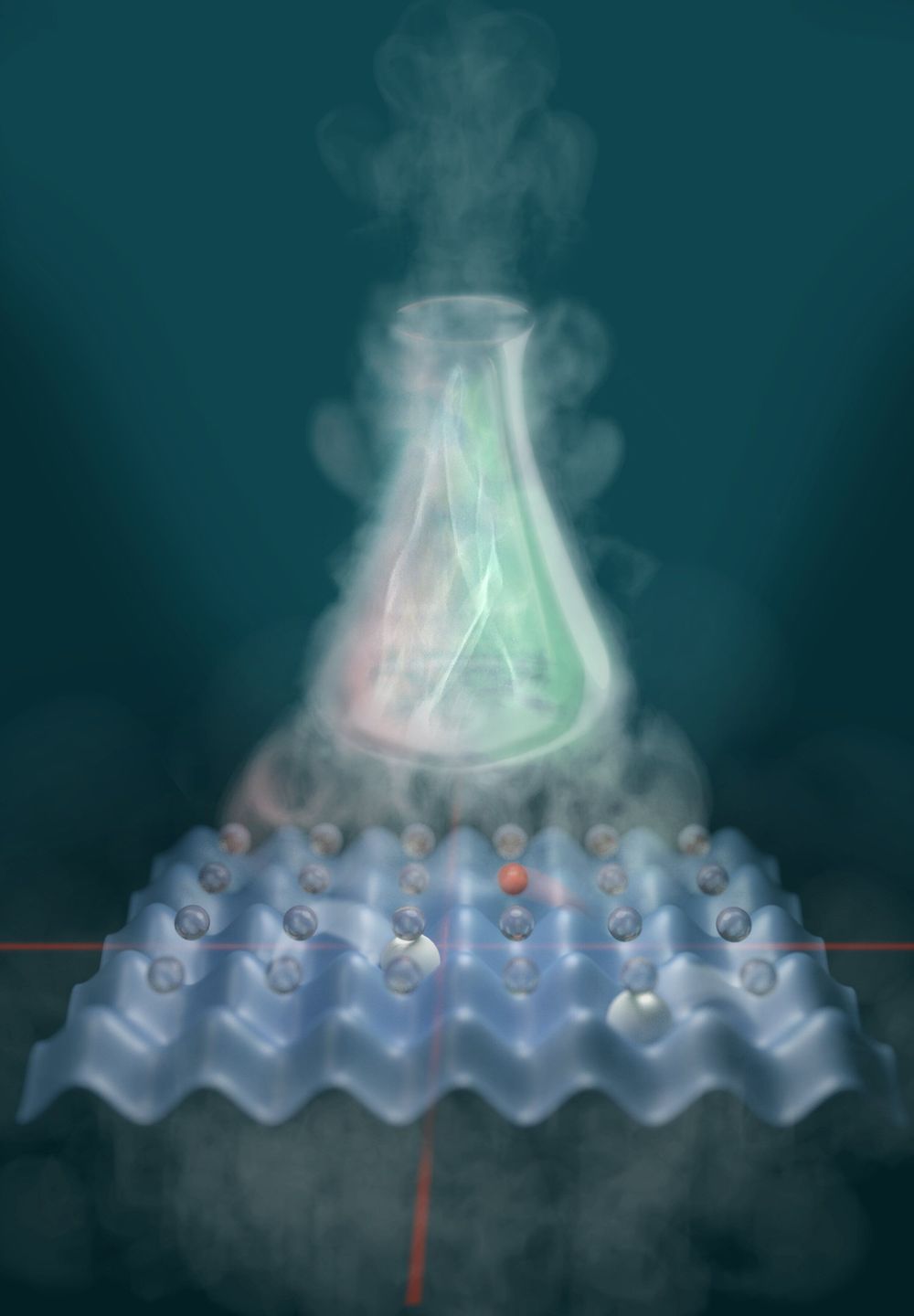

As a way out, in 1982, the American physicist Richard Feynman suggested the following: We should simulate quantum systems by reconstructing them as simplified models in the laboratory from individual atoms, which are inherently quantum, and therefore implying a parallelism of the possibilities by default. Today, quantum simulators are already in use, for example to imitate crystals. They have a regular, three-dimensional atomic lattice which is imitated by several intersecting laser beams, the “optical lattice.” The intersection points form something like wells in an egg carton into which the atoms are filled. The interaction between the atoms can be controlled by amplifying or attenuating the rays. This way researchers gain a variable model in which they can study atomic behavior very precisely.