“It was a huge surprise, we didn’t expect to find so many melanoma cancer cell markers in blood exosomes,” explains Hubert Girault, who heads up the Laboratory of Physical and Analytical Electrochemistry at EPFL Valais Wallis. Professor Girault and his team made the discovery almost by accident. Their findings, which have been published in the journal Chem, offer insight into how cancer cells communicate with each other and send information around the body.

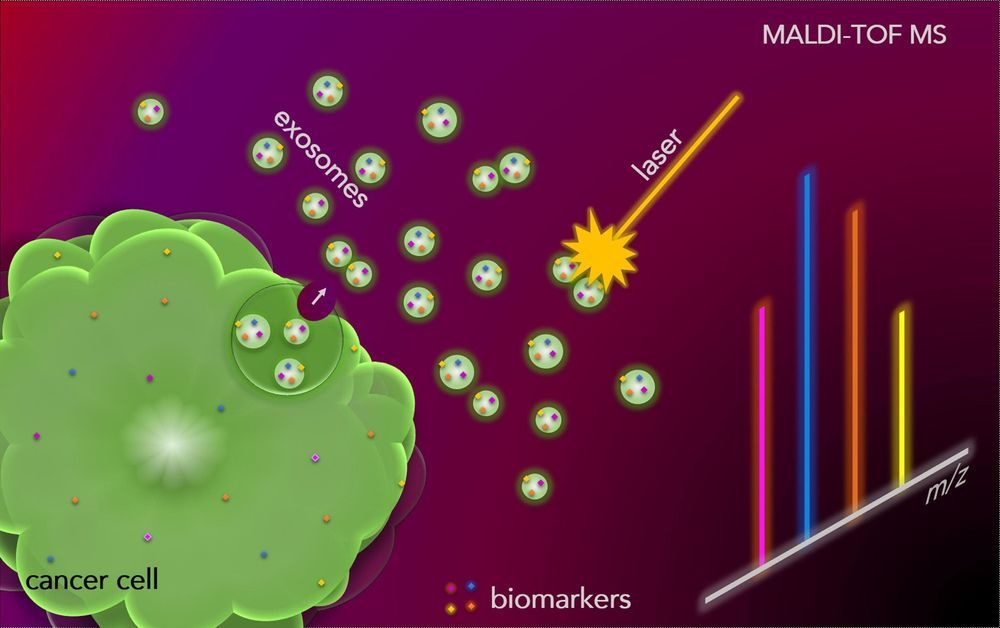

All biological cells excrete exosomes, microscopic spheres or vesicles that are less than 100 nanometers in size and contain a wealth of information in the form of nucleic acids, proteins and markers. Exosomes perform cell-to-cell signaling, conveying information between cells. Under the supervision of Senior Scientist Dr. Horst Pick, EPFL doctoral assistant Yingdi Zhu used cell culture and mass spectrometry to isolate melanoma cancer cell exosomes. She was able to identify cancer cell markers in exosomes for each stage of melanoma growth.

When analyzing the blood exosomes of melanoma patients, the researchers were surprised to discover large quantities of cancer cell markers. The blood collects and transports all the exosomes that the body generates. While healthy cells usually produce exosomes in small quantities, cancer cells produce many more. But it was previously thought that these would be so diluted in the blood that they would be hard to detect. For Professor Girault, the discovery of large quantities of cancer cell markers in blood exosomes raises numerous questions about signaling between cancer cells, which until now were not thought to communicate over longer distances within the body.