I have fond memories of both of my grandfathers as a boy growing up in the American Southwest. My mother’s father was a master gardener, able to grow plants in an arid environment that should have thrived only in tropical rainforests. Botanists from the Department of Biology at the local university surveyed his garden, and promptly asked him to help with problems they were experiencing in their greenhouses. There were large fruit trees scattered throughout his backyard perfect for climbing and eating apples, peaches, or cherries fresh off the branch. The foliage of these trees was dense, making it possible to hide and pounce down on unsuspecting younger brothers or cousins wandering too near the danger zone. Not saying I ever did such a thing, just saying it was possible. You know?

Every Friday night we ate dinner at my mother’s parents’ house. I poignantly remember an after dinner ritual. My grandfather would retire to his recliner, toothpick in his mouth, and instruct one of his grandchildren to turn on the bulky multicomponent console color television with built in radio, turntable, and speakers. It was time to watch Friday night boxing. There was no remote control, we kids were the channel changers and volume knob manipulators. My grandfather was usually not an emotional man, but he would become quite animated and occasionally agitated watching the fight, particularly if there was a boxer he favored in the match. The grandchildren enjoyed watching him more than we did the pugilists on the flickering television screen.

My father’s father, on the other hand, was a wrestling fan. By wrestling, I mean the wrestling seen on Saturday afternoon television featuring men in tight shorts, outlandish costumes, some wearing hoods or masks over their heads, entering the ring wearing colorful capes to either wild applause or catcalls and hisses, bouncing off the ropes to clothesline their onrushing opponent, and jumping from the turnbuckles to land on their hapless opponent laid out on the mat below. Even to a boy it was obvious bad theater and fraud, but I enjoyed watching my grandfather yelling at the television, berating the bad guys and the referees during these spectacles. He knew the name of every hero and villain, and he would hurl epitaphs at the masked men in tight wrestling suites while openly cheering for those he admired. He particularly loved the chaos of tag team matches, guaranteed to degenerate into a free-for-all with all the combatants in the ring, throwing chairs, and occasionally even body slamming the referee to the canvas. I still remember some of the names and can mentally visualize the antics; Gene Kiniski, The Sheik, Ray Mendoza, Dory Funk Jr., Terry Funk, Mad Dog Vachon, Hard Boiled Haggarty, Raul Reyes, Killer Kowalski, and Johnny Valentine. As I grew older I mistakenly pointed out these matches were all rehearsed and the outcomes were scripted; this wasn’t real sport. He fixed me with a glare, informed me I was getting, “a little too big for my britches”, and asked me if I thought 250 lb. men climbing to the top of the ropes to hurl themselves on their foe below, or the prostrate , seemingly stunned wrestler on the mat absorbing the flying blow delivered from above should be considered as anything less than athletic.

Good point. I wouldn’t want to do it.

Cancer patients and caregivers grapple with malignant disease every day. Surgical oncology is an unusual, but not unique, sub-specialty area in surgical care. Many surgeons will enter the lives of their patients for an acute illness or event, perform the indicated operation to improve their condition, care for them in the hospital, and then see them for one or two post-operative visits in the office before discharging them on to the rest of their lives. Some surgical sub-specialties, including surgical oncology, follow their patients longitudinally. All of the oncology-related specialties follow their patients for years, if not for the lifetime of our patients after a diagnosis of cancer. We are watching for the success of our treatment, evidence of any recurrent or new metastatic disease, and treating any symptoms or problems related to the therapies we deliver. We get a chance to know our patients and their families, and to watch how they respond to a diagnosis of cancer and to living with the ever-present specter of possible return of malignant disease.

I admire the pluck and defiance of patients who have a “never give up” attitude. One of those patients is on my mind today. When I walked into an examination room to meet him, he sprang to his feet, grasped my hand and shook it vigorously, smiled a dazzling white smile, and then gave me a bear hug. Effusive. His first words, “Doc, you’re going to help me beat this thing!” At this point he was still shaking my hand, his grip getting tighter, so I politely asked him to release my hand lest I be unable to perform an operation on him because of damaged digits. He laughed and immediately cut me loose, allowing circulation to return to my fingers. We sat down to talk. I was not surprised this gentleman had an impressive grip. He was in his late 40s and built like a football running back or rugby player. I actually asked him if he had been a football player. He feigned disgust and exasperation and said, “No, I’m a real athlete. I am a wrestler.” As I explored his history it turned out he had been a collegiate wrestler of significant accomplishment and repute. After completing his collegiate career, he founded a successful business and spent his time raising his family, expanding his business acumen, and refereeing high school and college wrestling matches around his home state.

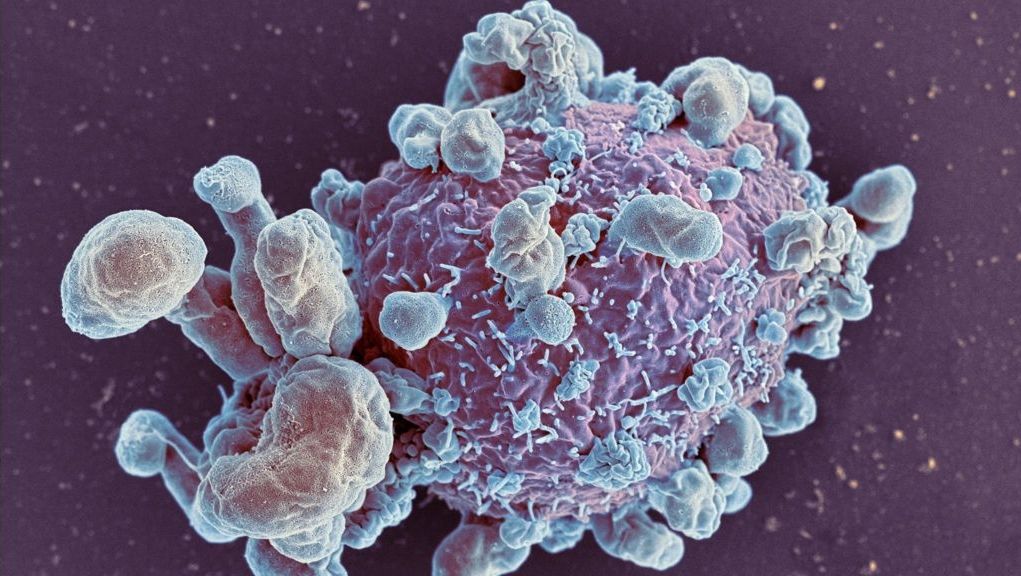

I was seeing this man for a diagnosis of colorectal cancer liver metastasis. Eight months prior to our initial meeting, he noticed some blood in his bowel movements and made an appointment with his primary care physician. His doctor noted that he did have blood on a rectal exam and that he was slightly anemic on blood tests. He had never before had a colonoscopy and there was no family history of colon cancer. A gastroenterologist was consulted and a colonoscopy revealed a colon cancer. The patient underwent an operation in his hometown to remove the malignant colon tumor. The gross and microscopic review of the surgical resection specimen by a pathologist discovered cancer in several lymph nodes near the primary tumor, and a biopsy of a liver tumor performed by the surgeon confirmed liver metastasis in the right lobe of his liver. Stage IV disease, signifying blood-borne spread, successful implantation, and growth of malignant cells from the colon cancer to another organ, his liver.

The patient recovered from his colon operation at a meteoric pace (his hometown surgeon’s description when I spoke to him), and then received six months of systemic intravenous chemotherapy. He was referred to me to address the sole clinically evident site of malignant disease, a tumor in the right lobe of his liver. I use the statement “clinically evident” purposefully, on our state-of-the-art computerized tomography (CT) scans the radiologists and I did not detect any suspicious tumors or “lesions” in his lungs, lymph nodes, or peritoneal cavity. Just a solitary liver metastasis smack dab in the middle of the right lobe. An almost Pavlovian circumstance for a hepatobiliary surgical oncologist who loves to attack and remove liver malignancies in this remarkably fit, healthy young man.

This gentleman was one of the most energetic, positive attitude, “let’s get this done” people I have met in any aspect of my life. We talked for about half an hour during our first visit, and I performed a physical examination. I reviewed the CT scans we performed and the pathology information he brought with him. He had a 5 cm liver tumor which originally was almost 8 cm in diameter. The tumor volume reduction indicted a positive response to chemotherapy. In oncology, numerous studies have indicated patients showing shrinkage of their tumors with chemotherapy tend to have a longer survival time after surgical and other anti-cancer therapies. It’s all statistics and probabilities; the bottom line is we can never know what’s going to happen specifically to one given patient. This patient told me he was ready for me to operate and “get this devil out of me” as quickly as possible.

The next week I performed an exploratory laparotomy. Surgeons are multi-sensory creatures. We like to visually inspect the area of the operation, but we also like to feel. I palpated the lymph nodes near the blood vessels heading into his liver. Several of them felt hard like small stones despite not being enlarged. I removed all of these regional lymph nodes adjacent to the liver and then completed a routine right hepatectomy. Upon checking the remainder of the belly cavity visually and tactilely, there was no evidence of tumor to be found at any other site.

My patient was up walking laps in the hallways of the surgical unit the night of his operation. Several nurses told me they were exhausted just watching him. He was indefatigable. He consistently had a huge smile on his face and greeted everyone with a bone-crushing handshake. He left the hospital only four days after his operation. As he stated, “All systems are working, I’m outta here.”

See ya!

I saw him in clinic the following week and we reviewed the results from surgery. I explained to him the pathologist found not only the single liver tumor we knew was present, but also three additional 2–3 mm tumors were detected near the large tumor. None of these tumors was close to the liver transection line, we had achieved a tumor margin-negative operation. Furthermore, three of the twelve lymph nodes removed from around the blood vessels supplying his liver contained metastatic colorectal cancer. He was nonplussed, and asked if it was still possible to be cured. The question I get every week. I explained the finding of the small tumors in the liver combined with lymph node metastases meant there was a higher probability he could have microscopic cancer cells hiding elsewhere in his body. In other words, his chance for long-term cancer free survival was significantly reduced, but was not zero. I finished with the assurance I planned to follow him closely and watch for any recurrence. That earned me a grand smile, more damage to my right hand, and an exhalation-inducing embrace. He returned home and spoke to his medical oncologist. They decided to proceed with another six months of a different chemotherapy regimen. At the end of the second six months of cytotoxic drugs, he returned to see me in clinic. All of our blood tests and CT scans on him showed no problem, no clinically evident cancer.

I wasn’t sure if my right hand or chest was going to remain intact thanks to this patient.

The good results and good news were short lived. Six months later, a blood test we measure in patients with colorectal cancer called CEA, an abbreviation for carcinoembryonic antigen, was elevated in him. When I saw his lab results, I immediately scrolled through his CT scans, and then quietly cursed at the computer screen. He had four new tumors in the hypertrophied left lobe of his liver along with a dozen or more small lung metastases scattered throughout both lungs. I walked into an examination room to tell him the news. He knew from my face I was about to drop a bomb on him. Before I could say anything, he stood up, hugged me, and to my amazement said, ”We’ll beat this thing!” I reassured him we were in the fight together and I then went over all of his results. He sat quietly nodding, occasionally asking for clarification, and finally asked, “Okay, what’s our next move?” I spoke with my colleagues in medical oncology and we determined a new sequence of drugs to treat him for this rapid recurrence.

At a visit with me three months later, he launched the question patients often ask, he wanted to know how long he would live. He was a motivated, insightful, intelligent individual and as we sat together in a clinic room, he rifled through copies of scientific papers describing chemotherapy and novel treatments for stage IV colorectal cancer. He noted from his reading the median survival with the chemotherapy drugs he was receiving ranged from 18–24 months. I replied those perceptions and statistics were correct, but there was no way to predict if he would live less or more time than the average. He laughed, tossed the research papers on the floor, and said, “These don’t describe me!”

After six months of additional chemotherapy, this gentleman’s lung metastases had completely disappeared on CT scans of the chest, and the liver metastases appeared to be calcified scar tissue. His CEA blood test had returned to a normal value. After considering his situation and excellent anti-tumor response in a tumor board meeting, my colleagues and I determined we would stop chemotherapy and follow him. This we did with blood tests, CT scans, and physical examinations every three months for another year. At the one year off chemotherapy mark, his CEA value was again elevated and CT scans revealed recurrence in the liver, lungs, and peritoneal cavity. Grimly, I walked into the examination room to have a heartrending discussion. I reviewed the test results as his wife quietly wept, and before addressing me, he turned to her, gave her a hug, and told her he would be all right. He pivoted to me and flashed a dazzling smile saying, “Remember, we are in this together.”

Yes we are. Based on probabilities, patterns, and the rapid recurrence of his cancer in multiple sites, this man would not have been predicted to survive more than 2 or 3 years after his initial cancer diagnosis. I mentioned previously he was on my mind because I received a note from his brother recently informing me he had finally lost his battle and had passed away. It was almost 8 years from the time of his original cancer diagnosis. Throughout all of those years I saw him every 3 months and arranged for him to see numerous specialists and medical oncologists administering a variety of new clinical trials for colorectal cancer. His medical oncologist at home is very active in treating patients with established and new regimens for gastrointestinal malignancies. When we spoke on the phone about our mutual patient, it was always with a note of admiration for his courage and formidible spirit.

I grew up watching boxers and faux wrestlers (performance athletes?) with my grandfathers. Several of the wrestlers we watched on Saturday afternoon television had been college wrestlers, some even competing in the Olympics. They were indeed athletes. Not great actors, but athletes, nonetheless. Perhaps the ability to work hard, to strive, to endure pain and discomfort and defeat is what led my patient, the wrestler, to survive as long as he did. I have seen similar powerful and courageous efforts from patients of all ages and backgrounds. I am reminded of a verse of the lyrics from one of my favorite songs from childhood, “The Boxer”, performed by Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel.

In the clearing stands a boxer,

and a fighter by his trade

And he carries the reminders

of every glove that laid him down or cut him

till he cried out, in his anger and his shame,

“ I am leaving, I am leaving”,

but the fighter still remains.

Warrior terminology abounds in the cancer lexicon. “The War on Cancer.” “She lost her battle with cancer.” “I am fighting cancer.” ‘We are going to attack your cancer with every weapon in our arsenal.” “He refuses to surrender and will keep battling.” “She is soldiering on through this fight with cancer.” “I am going to beat and defeat this cancer.” “It was a courageous fight.” “We have your cancer on the ropes.”

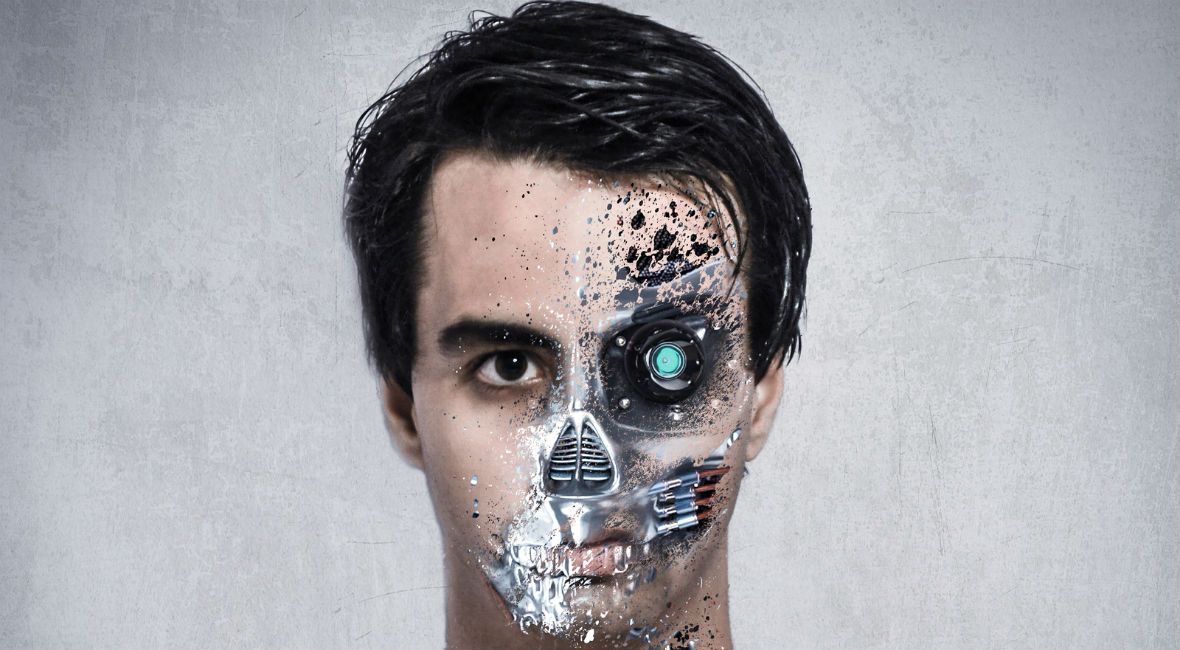

Patients diagnosed with cancer and treated with our multidisciplinary approaches are knocked down physically and emotionally, but they pick themselves up off the canvas and struggle on. They carry the reminders of the acute and chronic side effects from cytotoxic chemotherapy, the radiation-induced skin and functional organ changes, and the surgical scars, complications, and impairments imposed by the blades of surgical oncologists like me. Though sometimes they want to, they don’t leave. They remain. They maintain. I respect the effort, the invincible spirit, and the patients who don’t give a damn about the odds or probabilities; they are going out swinging. We are tag team partners in Oncology, entering the ring to attack a patient’s cancer with every move and method we know. Hell, I’ll even throw a few chairs if it will help.

Indomitable. The wrestler. I honor you.