Researchers determined that when introduced into damaged mouse or donated human livers, these lab-grown tissues could integrate into bile ducts and function normally.

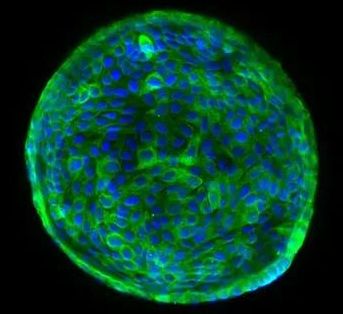

ABOVE: A human cholangiocyte–derived organoid with nuclei in blue and the cytoplasm of bile duct cells in green FOTIOS SAMPAZIOTIS, TERESA BREVINI

Scientists have shown over the past decade or so that organoids—small, organ-like structures grown in culture from stem cells—can integrate into many organs, including the liver, lungs, and guts of mice, and repair defects. In a study published today (February 18) in Science, researchers have advanced this approach in human tissue, and demonstrate that organoids derived from adult cholangiocytes, the cells that line the bile ducts, can integrate into human livers from deceased organ donors. The findings pave the way for new treatments for liver diseases, as well as for the repair of donated organs to make more available for transplant.

“It is quite spectacular if you can really functionally repair the liver by injecting cholangiocytes into an intact liver,” says Hans Clevers, a developmental biologist at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. He was not involved in the work, but in research led by former postdoc Meritxell Huch, his group showed in 2015 that it was possible to grow human liver organoids in culture and that they could be successfully transplanted into mice—work the authors of the new study have built upon.