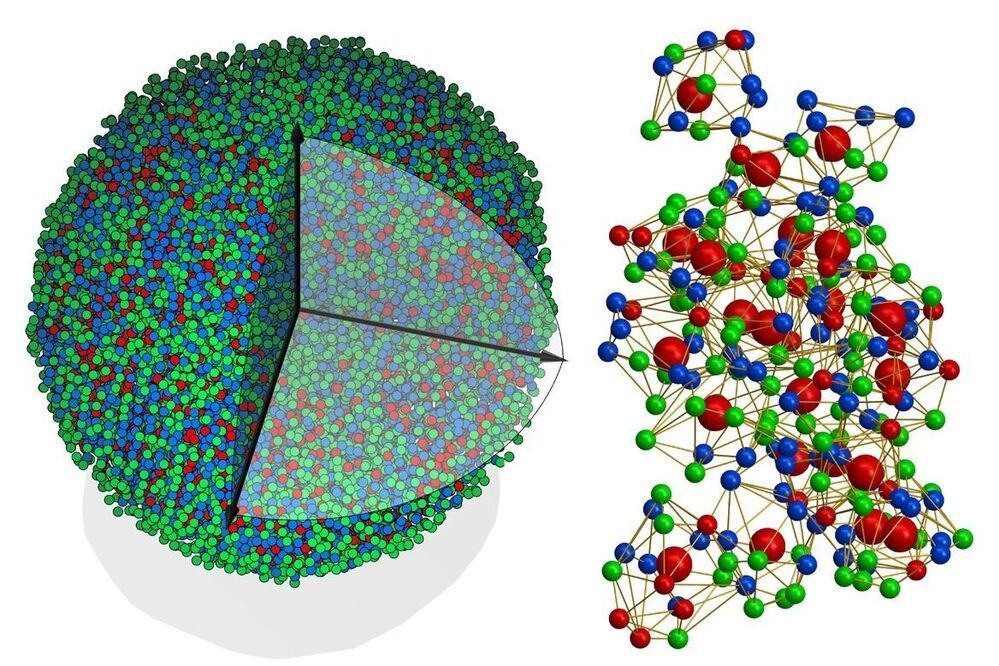

Glass, rubber and plastics all belong to a class of matter called amorphous solids. And in spite of how common they are in our everyday lives, amorphous solids have long posed a challenge to scientists.

Since the 1910s, scientists have been able to map in 3D the atomic structures of crystals, the other major class of solids, which has led to myriad advances in physics, chemistry, biology, materials science, geology, nanoscience, drug discovery and more. But because amorphous solids aren’t assembled in rigid, repetitive atomic structures like crystals are, they have defied researchers’ ability to determine their atomic structure with the same level of precision.

Until now, that is.