The researchers let the cell clusters assemble in the right proportions and then used micro-manipulation tools to move or eliminate cells — essentially poking and carving them into shapes like those recommended by the algorithm. The resulting cell clusters showed the predicted ability to move over a surface in a nonrandom way.

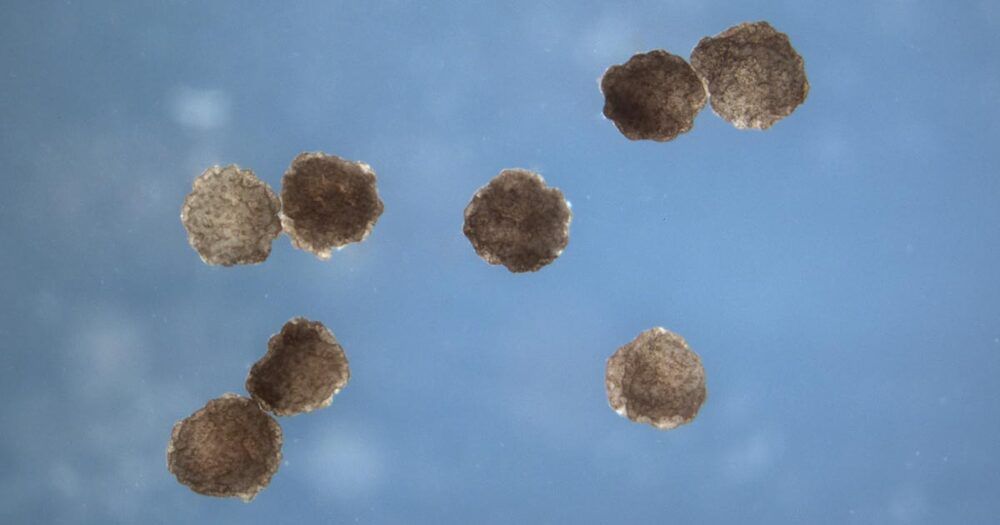

The team dubbed these structures xenobots. While the prefix was derived from the Latin name of the African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis) that supplied the cells, it also seemed fitting because of its relation to xenos, the ancient Greek for “strange.” These were indeed strange living robots: tiny masterpieces of cell craft fashioned by human design. And they hinted at how cells might be persuaded to develop new collective goals and assume shapes totally unlike those that normally develop from an embryo.

But that only scratched the surface of the problem for Levin, who wanted to know what might happen if embryonic frog cells were “liberated” from the constraints of both an embryonic body and researchers’ manipulations. “If we give them the opportunity to re-envision multicellularity,” Levin said, then his question was, “What is it that they will build?”