The earliest bones, however, were very different from human skeletons today. In the prehistoric past, bone was more like concrete, growing on the exterior of fish to provide a protective shell. But according to a new study in the journal Science Advances, the first bones with living cells—like those found in humans—evolved about 400 million years ago and acted as skeletal batteries: They supplied prehistoric fish with minerals needed to travel over greater distances.

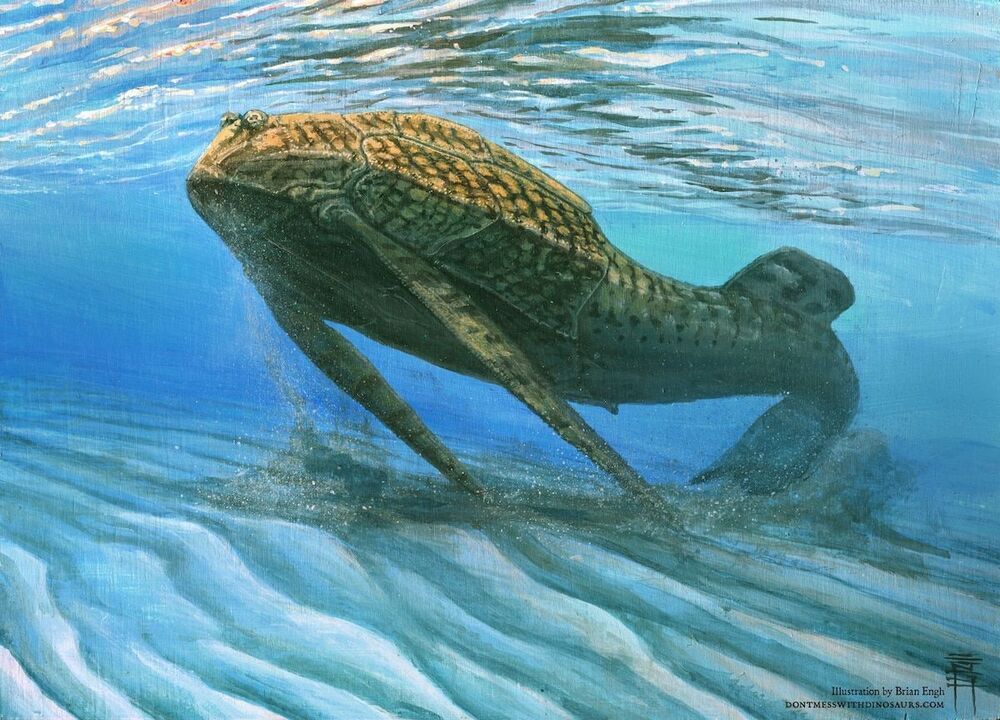

The fossilized creatures in the analysis are known as osteostracans. “I affectionately call them beetle mermaids,” says Yara Haridy, a doctoral candidate at the Berlin Museum of Nature and lead author of the study. These fish had a hard, armor-encased front end and a flexible tail growing out the back. They had no jaws, and their bone tissue encased their bodies. These kinds of fish are critical to understanding the origins of the hard parts that shaped vertebrate evolution.