Hereditary hearing loss is one of the most common disabilities among newborns, affecting approximately 1 in 1000 live-born babies. Most forms of hereditary hearing loss are nonsyndromic; 80% of affected newborns have hearing loss that is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, and in the remaining 20%, inheritance shows a dominant pattern.1

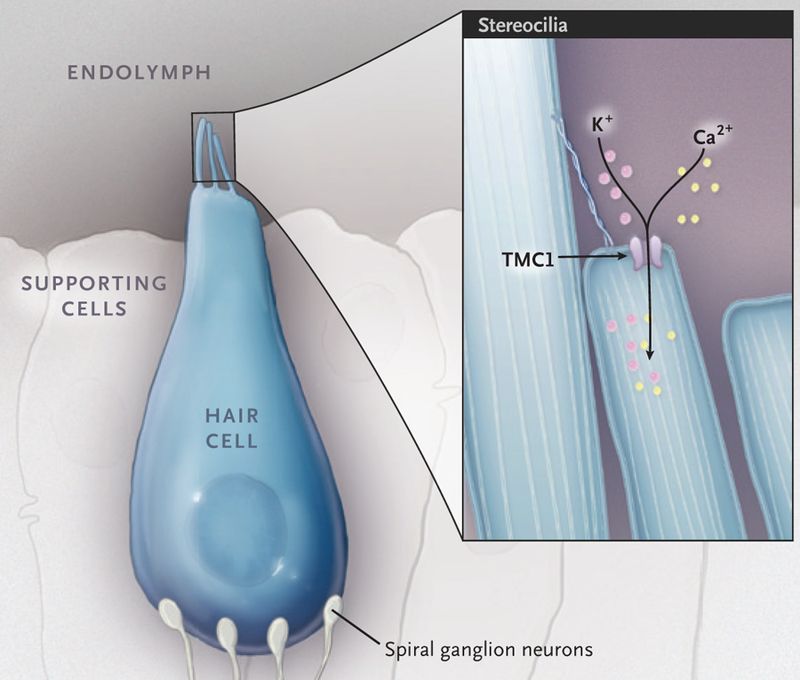

Many forms of hereditary hearing loss are caused by mutations in genes that affect the formation and function of cochlear hair cells — highly specialized sensory cells that play an important role in the detection and processing of sound.1 The hair cell has bundles of hair-like projections, called stereocilia, on its apical surface ( Fig. 1 ). The deflection of these bundles by sound results in the opening of mechanotransduction ion channels, which are located at the tips of the stereocilia, and consequently, in the depolarization of the hair-cell membrane. Mutations that affect the protein transmembrane channel-like 1 (TMC1), an integral component of the mechanotransduction complex, cause autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive forms of hearing loss.2 Correction of the dominant form of hearing loss in a mouse model of Tmc1 (termed “Beethoven”) was recently reported by Gao and colleagues.3