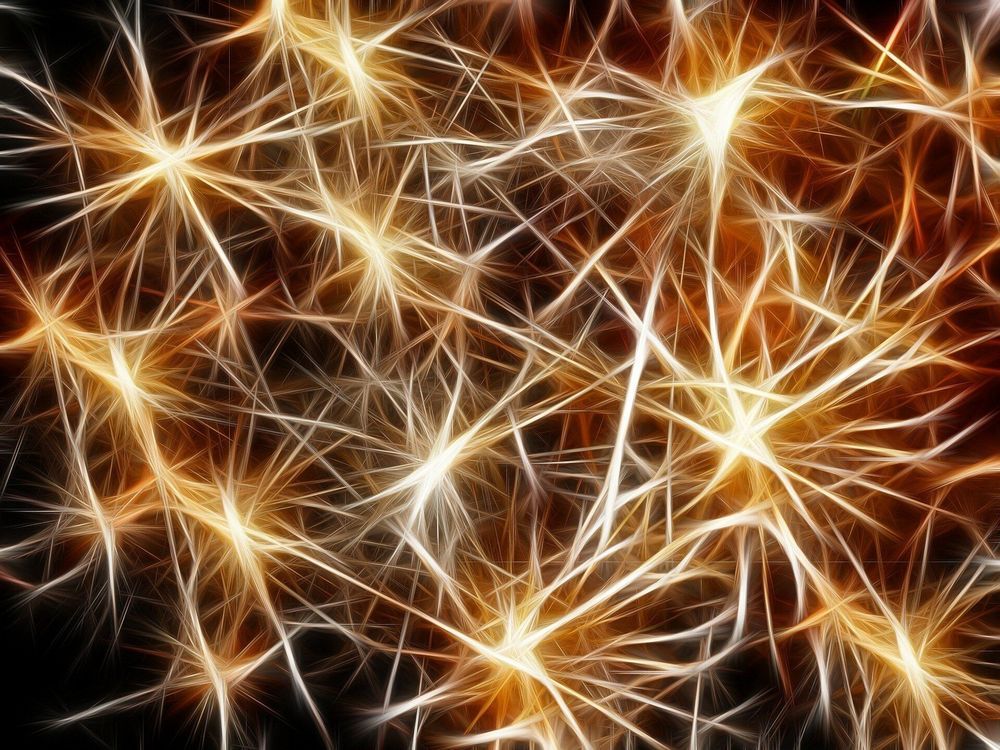

Researchers long wondered how the billions of independent neurons in the brain come together to reliably build a biological machine that easily beats the most advanced computers. All of those tiny interactions appear to be tied to something that guarantees an impressive computational capacity.

Over the past 20 years, evidence mounted in support of a theory that the brain tunes itself to a point where it is as excitable as it can be without tipping into disorder, similar to a phase transition. This criticality hypothesis asserts that the brain is poised on the fine line between quiescence and chaos. At exactly this line, information processing is maximized.

However, one of the key predictions of this theory—that criticality is truly a set point, and not a mere inevitability—had never been tested. Until now. New research from Washington University in St. Louis directly confirms this long-standing prediction in the brains of freely behaving animals.