Using newly refined analysis methods, scientists have discovered that a North Korean nuclear bomb test last fall set off aftershocks over a period of eight months. The shocks, which occurred on a previously unmapped nearby fault, are a window into both the physics of nuclear explosions, and how natural earthquakes can be triggered. The findings are described in two papers just published online in the journal Seismological Research Letters.

The September 3, 2017 underground test was North Korea’s sixth, and by far largest yet, yielding some 250 kilotons, or about 17 times the size of the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. Many experts believe the device was a hydrogen bomb—if true, a significant advance from cruder atomic devices the regime previously exploded. The explosion itself produced a magnitude 6.3 earthquake. This was followed 8.5 minutes later by a magnitude 4 quake, apparently created when an area above the test site on the country’s Mt. Mantap collapsed into an underground cavity occupied by the bomb.

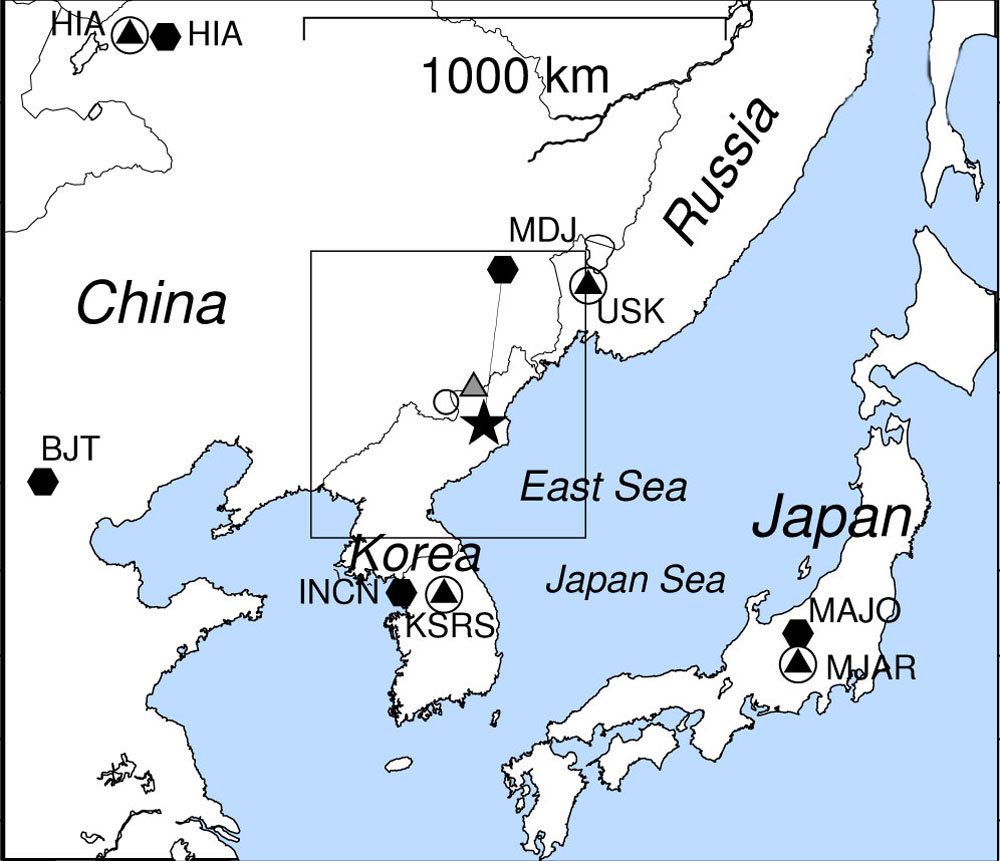

The test and collapse were picked up by seismometers around the world and widely reported at the time. But later, without fanfare, seismic stations run by China, South Korea and the United States picked up 10 smaller shocks, all apparently scattered within 5 or 10 kilometers around the test site. The first two came on Sept. 23, 2017; the most recent was April 22, 2018. Scientists assumed the bomb had shaken up the earth, and it was taking a while to settle back down. “It’s not likely that there would be so many events in that small area over a small period of time,” said the lead author of one of the studies, Won-Young Kim, a seismologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “These are probably triggered due to the explosion.”