Using roundworms, one of Earth’s simplest animals, Rice University bioscientists have found the first direct link between a diet with too little vitamin B12 and an increased risk of infection by two potentially deadly pathogens.

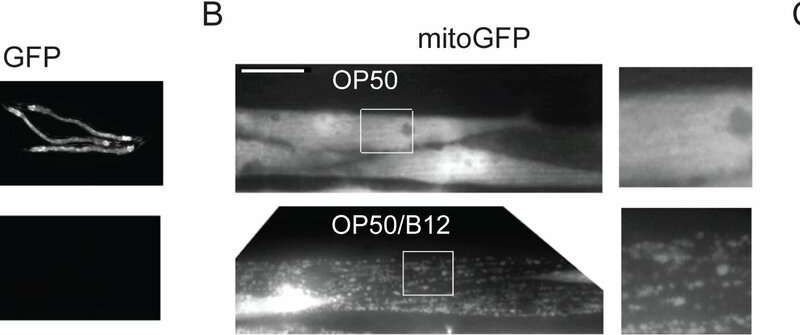

Despite their simplicity, 1-millimeter-long nematodes called Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) share an important limitation with humans: They cannot make B12 and must get all they need from their diet. In a study published today in PLOS Genetics, researchers from the lab of Rice biochemist and cancer researcher Natasha Kirienko describe how a B12-deficient diet harms C. elegans’ health at a cellular level, reducing the worms’ ability to metabolize branched-chain amino acids (BCAA). The research showed that the reduced ability to break down BCAAs led to a toxic buildup of partially metabolized BCAA byproducts that damaged mitochondrial health.

Researchers studied the health of two populations of worms, one with a diet sufficient in B12 and another that got too little B12 from its diet. Like the second population of worms, at least 10 percent of U.S. adults get too little B12 in their diet, a risk that increases with age.