Using a few wires and sponges, in ordinary homes around the world, people are trying to hack their own minds. Thanks to a 2002 study that found a link between brain transcranial direct current stimulation and better motor task performance, “do-it-yourself” brain stimulation has become a growing movement among those who want to improve a whole host of cognitive and psychological functions, including language skills, mood and memory.

Scientists are split about the practice: Some say that while brain stimulators might not work as advertised (the ones available to purchase can cost hundreds of dollars), these devices are more-or-less safe. Others think the technique could cause damage, even if done in a controlled, clinical setting. Though “brain hackers” may be disappointed with their own results, their hope about the technology’s potential is rooted in an increasing amount of evidence.

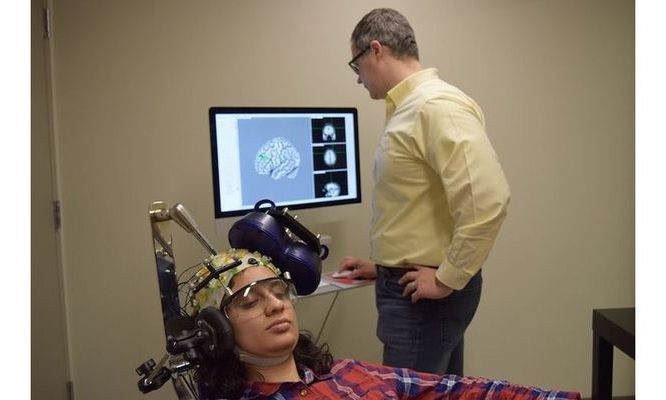

The earliest clinical uses of brain stimulation date back to nearly 2000 years ago, when physician Scribonius Largus recommended the use of electric rayfish to treat headaches and neuralgia. By the 1980s, researchers began designing non-invasive stimulators and brain implants for treating specific diseases. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) — a non-invasive treatment that uses direct electrical currents to stimulate specific parts of the brain — has been shown, in a few small studies, to purportedly improve language skills, boost memory and strengthen reflexes. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), another non-invasive procedure, is sometimes used to treat depression. And clinical trials are underway to see if stimulating the brain can treat other medical conditions, such as Parkinson’s.