The adult brain has learned to calculate an image of its environment from sensory information. If the input signals change, however, even the adult brain is able to adapt − and, ideally, to return to its original activity patterns once the perturbation has ceased. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology in Martinsried have now shown in mice that this ability is due to the properties of individual neurons. Their findings demonstrate that individual cells adjust strongly to changes in the environment but after the environment returns to its original state it is again the individual neurons which reassume their initial response properties. This could explain why despite substantial plasticity the perception in the adult brain is rather stable and why the brain does not have to continuously relearn everything.

Everything we know about our environment is based on calculations in our brain. Whereas a child’s brain first has to learn the rules that govern the environment, the adult brain knows what to expect and, for the most part, processes environmental stimuli in a stable manner. Yet even the adult brain is able to respond to changes, to form new memories and to learn. Research in recent years has shown that changes to the connections between neurons form the basis of this plasticity. But, how can the brain continually change its connections and learn new things without jeopardizing its stable representation of the environment? Neurobiologists in the Department of Tobias Bonhoeffer in Martinsried have now addressed this fundamental question and looked at the interplay between plasticity and stability.

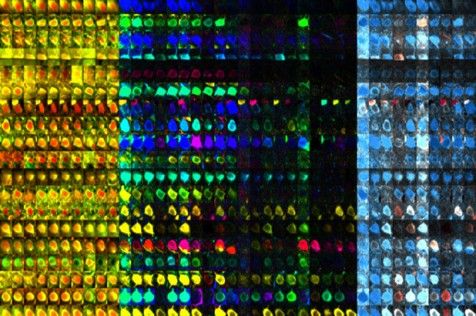

The scientists studied the stability of the processing of sensations in the visual cortex of the mouse. It has been known for about 50 years that when one eye is temporarily closed, the region of the brain responsive to that eye increasingly becomes responsive to signals from the other eye that is still open. This insight has been important to optimize the use of eye patches in children with a squint. “Thanks to new genetically encoded indicators, it has recently become possible to observe reliably the activity of individual neurons over long periods of time,” says Tobias Rose, the lead author of the study. “With a few additional improvements, we were able to show for the first time what happens in the brain on the single-cell level when such environmental changes occur.”