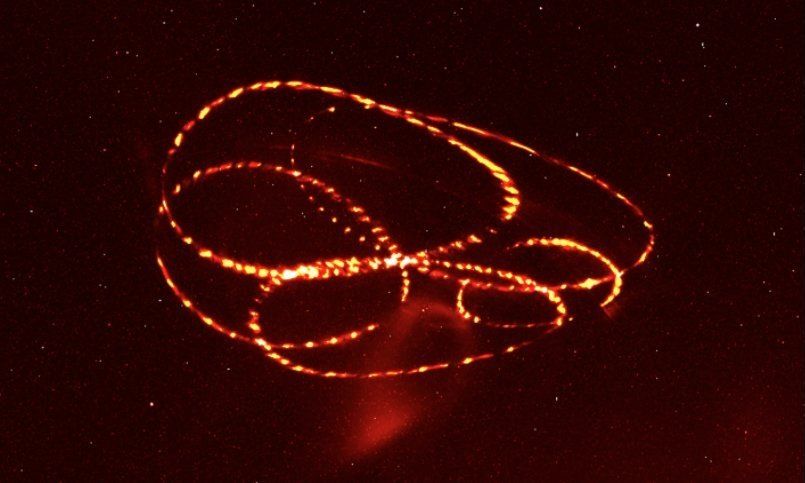

Well, here’s some terrifying news: There’s a Chinese space station out in the galaxy that is hurtling towards Earth, and it is expected to hit the planet on or around Apr. 1, 2018. There’s no stopping it, and scientists have stated that they really don’t have much control over it either. On top of that, it could either cause a lot of damage or it could do almost nothing. In other words, it’s a very unclear situation! The question on everyone’s mind is an important one: where is the Chinese space station going to crash? Do you need to be worried about being destroyed by a flying space station on Easter Sunday?

Here’s the deal: in 2016, China lost control of their first space station, called Tiangong-1, which is about the size of a school bus (so, yes, it’s very large). According to Vox, China had once been planning on trying to give the space station a controlled descent to Earth so that we didn’t all have to worry about having large pieces of it fall on or around our homes. That’s when things got more out of control: the space station malfunctioned, for reasons we still don’t really know. Due to “orbital decay” (which is defined as “the process of prolonged reduction in the altitude of a satellite’s orbit.” So, essentially, it’s when objects enter the Earth’s atmosphere and burn up), the space station has been heading towards Earth since it went off on its own.

The time has now come for that space station to hit Earth. It is said to be about 124 miles above the Earth, and is expected to crash through the atmosphere on or around Apr. 1, according to the European Space Agency. The good news is that a lot of it will burn up in the atmosphere. The bad news is that there will still be some heavy pieces that get through and hit the ground. Also bad news: we can’t control any of it. Oh, and no one knows where it will land.

Read more