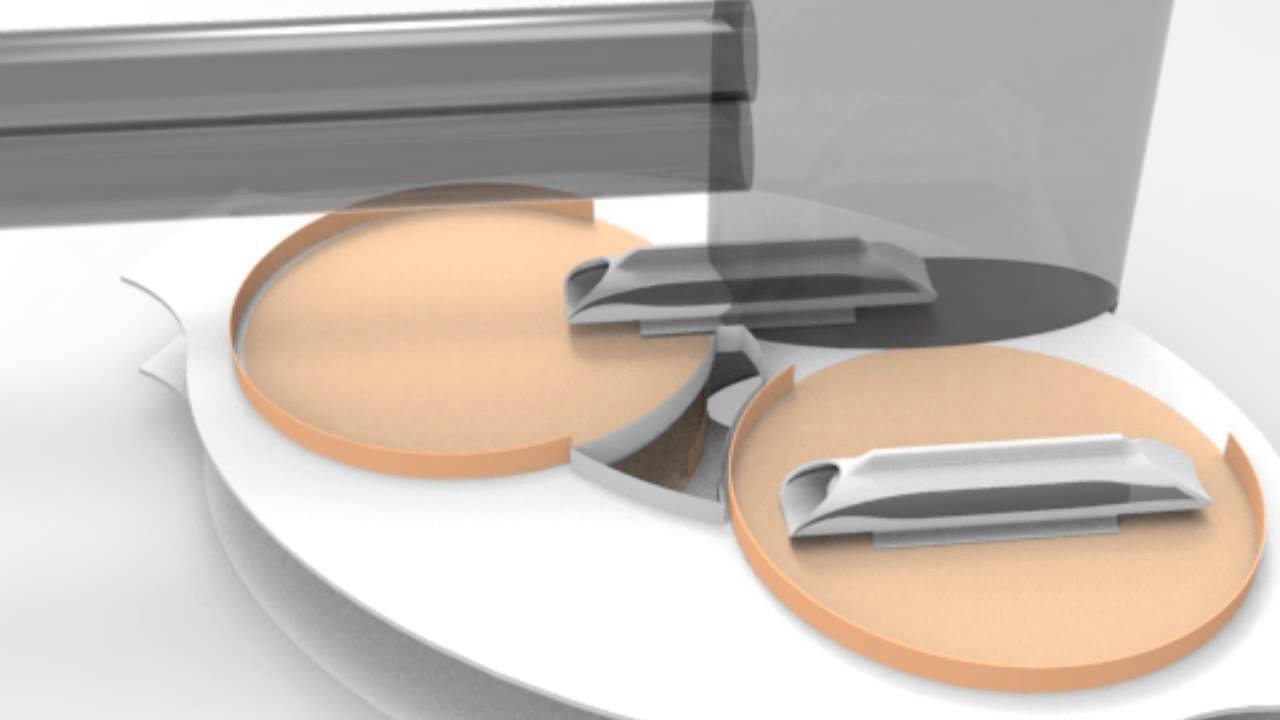

Australian scientists have designed a 3D silicon chip architecture based on single atom quantum bits, which is compatible with atomic-scale fabrication techniques — providing a blueprint to build a large-scale quantum computer.

Australian scientists have designed a 3D silicon chip architecture based on single atom quantum bits, which is compatible with atomic-scale fabrication techniques — providing a blueprint to build a large-scale quantum computer.

These people have got a leg — or an arm — up on the future.

Thanks to the latest advancements in medical science, amputees are becoming part robot, with awe-inspiring artificial limbs that would make Luke Skywalker jealous.

These new limbs come armed with microprocessors and electrodes that sense muscle movement. Others can be controlled by a smartphone app. People missing limbs often tried to hide their prosthetics, but these New Yorkers are showing them off with pride.

Rebekah Marine.

Rebekah Marine had the modeling bug from a young age, playing dress-up as a kid and getting her mom to take her to try out for modeling agencies in New York.

The one problem? She was born without part of her right arm.

“I was just kind of quickly denied from [agencies] based on my quote-unquote disability,” the 28-year-old says.

To many people, the introduction of the first Macintosh computer and its graphical user interface in 1984 is viewed as the dawn of creative computing. But if you ask Dr. Nick Montfort, a poet, computer scientist, and assistant professor of Digital Media at MIT, he’ll offer a different direction and definition for creative computing and its origins.

Defining Creative

“Creative Computing was the name of a computer magazine that ran from 1974 through 1985. Even before micro-computing there was already this magazine extolling the capabilities of the computer to teach, to help people learn, help people explore and help them do different types of creative work, in literature, the arts, music and so on,” Montfort said.

“It was a time when people had a lot of hope that computing would enable people personally as artists and creators to do work. It was actually a different time than we’re in now. There are a few people working in those areas, but it’s not as widespread as hoped in the late 70’s or early 80s.”

These days, Montfort notes that many people use the term “artificial intelligence” interchangeably with creative computing. While there are some parallels, Montfort said what is classically called AI isn’t the same as computational creativity. The difference, he says, is in the results.

“A lot of the ways in which AI is understood is the ability to achieve a particular known objective,” Montfort said. “In computational creativity, you’re trying to develop a system that will surprise you. If it does something you already knew about then, by definition, it’s not creative.”

Given that, Montfort quickly pointed out that creative computing can still come from known objectives.

“A lot of good creative computer work comes from doing things we already know computers can do well,” he said. “As a simple example, the difference between a computer as a producer of poetic language and person as a producer of poetic language is, the computer can just do it forever. The computer can just keep reproducing and, (with) that capability to bring it together with images to produce a visual display, now you’re able to do something new. There’s no technical accomplishment, but it’s beautiful nonetheless.”

Models of Creativity

As a poet himself, another area of creative computing that Montfort keeps an eye on is the study of models of creativity used to imitate human creativity. While the goal may be to replicate human creativity, Montfort has a greater appreciation for the end results that don’t necessarily appear human-like.

“Even if you’re using a model of human creativity the way it’s done in computational creativity, you don’t have to try to make something human-like, (even though) some people will try to make human-like poetry,” Montfort said. “I’d much rather have a system that is doing something radically different than human artistic practice and making these bizarre combinations than just seeing the results of imitative work.”

To further illustrate his point, Montfort cited a recent computer generated novel contest that yielded some extraordinary, and unusual, results. Those novels were nothing close to what a human might have written, he said, but depending on the eye of the beholder, it at least bodes well for the future.

“A lot of the future of creative computing is individual engagement with creative types of programs,” Montfort said. “That’s not just using drawing programs or other facilities to do work or using prepackaged apps that might assist creatively in the process of composition or creation, but it’s actually going and having people work to code themselves, which they can do with existing programs, modifying them, learning about code and developing their abilities in very informal ways.”

That future of creative computing lies not in industrial creativity or video games, but rather a sharing of information and revisioning of ideas in the multiple hands and minds of connected programmers, Montfort believes.

“One doesn’t have to get a computer science degree or even take a formal class. I think the perspective of free software and open source is very important to the future of creative programming,” Montfort said. “…If people take an academic project and provide their work as free software, that’s great for all sorts of reasons. It allows people to replicate your results, it allows people to build on your research, but also, people might take the work that you’ve done and inflect it in different types of artistic and creative ways.”

“AI is achievable, but it will take more than computer science and neuroscience to develop machines that think like people”

A very interesting article about the state of funding for aging research and about Buck and ex Geron Mike West.

As I mentioned in last week’s letter, I traveled to San Francisco last Monday with my friend Patrick Cox, who writes our Transformational Technology Alert newsletter. We had dinner with Dr. Mike West of Biotime and then spent the next morning at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging. Pat and I decided we would jointly report on what we learned. He has already written his part, which was published last week. I am going to reproduce portions of that letter, which highlight the conversation with Brian Kennedy and his team at the Buck Institute, and then add my own thoughts about our conversation with Mike West the previous night.

(Note that I am excerpting Patrick’s paid letter, which includes comments on companies in his portfolio, rather than his free weekly Transformational Technologies Tech Digest service. We agreed that it was important to do so in this one case, given the huge significance of the research involved and the Buck Institute’s relationship to it.)

Essentially, we looked at two aspects of aging. The Buck Institute is focused on how to slow down the aging process and reduce the symptoms (such as chronic diseases) that come with aging. Dr. Mike West and his colleagues, as well as a few other firms and researchers, are focused on using our own pluripotent stem cells in ways that would allow us to repair organs in our bodies, thus giving us the opportunity to “grow younger” again. (It’s not quite that simple, as I’ll try to explain later.)

We can build structures that resettle after quakes, and self-cooling homes – the trick is to 3D print custom building blocks, not whole buildings.

On October 26, the Center for Technology Innovation at Brookings hosted a forum to explore the impact of robots, artificial intelligence, and machine learning on the workforce and the provision of benefits traditionally supplied by—or in conjunction with—employers.

http://www.brookings.edu/events/2015/10/26-robotics-employment-social-benefits-west

Subscribe! http://www.youtube.com/subscription_center?add_user=BrookingsInstitution

Follow Brookings on social media!

Facebook: http://www.Facebook.com/Brookings

Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/BrookingsInst

Instagram: http://www.Instagram.com/brookingsinst

LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/com/company/the-brookings-institution

Current medical treatment boils down to six words: Have disease, take pill, kill something. But physician Siddhartha Mukherjee points to a future of medicine that will transform the way we heal.

TEDTalks is a daily video podcast of the best talks and performances from the TED Conference, where the world’s leading thinkers and doers give the talk of their lives in 18 minutes (or less). Look for talks on Technology, Entertainment and Design — plus science, business, global issues, the arts and much more.

Find closed captions and translated subtitles in many languages at http://www.ted.com/translate

Follow TED news on Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/tednews

Like TED on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TED