With modern innovations such as artificial intelligence, virtual reality, wi-fi, tablet computing and more, it’s easy for man to look around and say that the human brain is a complex and well-evolved organ. But according to Author, Neuroscientist and Psychologist Gary Marcus, the human mind is actually constructed somewhat haphazardly, and there is still plenty of room for improvement.

“I called my book Kluge, which is an old engineer’s word for a clumsy solution. Think of MacGyver kind of duct tape and rubber bands,” Marcus said. “The thesis of that book is that the human mind is a kluge. I was thinking in terms of how this relates to evolutionary psychology and how our minds have been shaped by evolution.”

Marcus argued that evolution is not perfect, but instead it makes “local maxima,” which are good, but not necessarily the best possible solutions. As a parallel example, he cites the human spine, which allows us to stand upright; however, since it isn’t very well engineered, it also gives us back pain.

“You can imagine a better solution with three legs or branches that would distribute the load better, but we have this lousy solution where our spines are basically like a flag pole supporting 70 percent of our body weight,” Marcus said.

“The reason for that is we’re evolved from tetrapods, which have four limbs and distribute their weight horizontally like a picnic table. As we moved upright, we took what was closest in evolutionary space, which is what took the fewest number of genes in order to give us this new kind of system of standing upright. But it’s not what you would have if you designed it from scratch.”

While Marcus’ book talked about the typical notion in evolutionary psychology that we have evolved to the optimal, he also noted that the human mind works as a function of two pathways, both the optimal performance and our brains’ history. To that end, he sees evolution as a probabilistic process of genes that are nearby, which aren’t necessarily those that are best for a given solution.

“A lot of the book was actually about our memories. The argument I made was that, if you really want a system of brain that does the thing humans do, you would want a kind of memory system that we find in computers, which is called location addressable memory,” Marcus explained.

“With location addressable memory, I’m going to store something in location seven or location eight or nine, and then you’re guaranteed to be able to go back to that thing you want when you want it, which is why computer memory is reliable. Our memory is not even remotely reliable. I can forget what I was going to say or forget where I parked my car. Our memories are nothing even close to the theoretical optimum that a computer shows us.”

Enhancing our minds, and our memories, won’t happen overnight, Marcus said. One might have a “brain like a computer” in theory, but he believes a more evolved, computer-like human brain is thousands of years away.

“There is what I call ‘evolutionary inertia’ that says once something is in place, it’s very hard for evolution to change it. If you change one or two genes, you might have an organism that survives. If you change several hundred, most likely, things are gonna’ break.”

In other words, evolution is the ultimate resourceful engine. Most evolutionary changes are small, since the brain tends to tweak the existing parts rather than start from scratch, which would be a more costly and rather inefficient solution in a survival-of-the-fittest-type world.

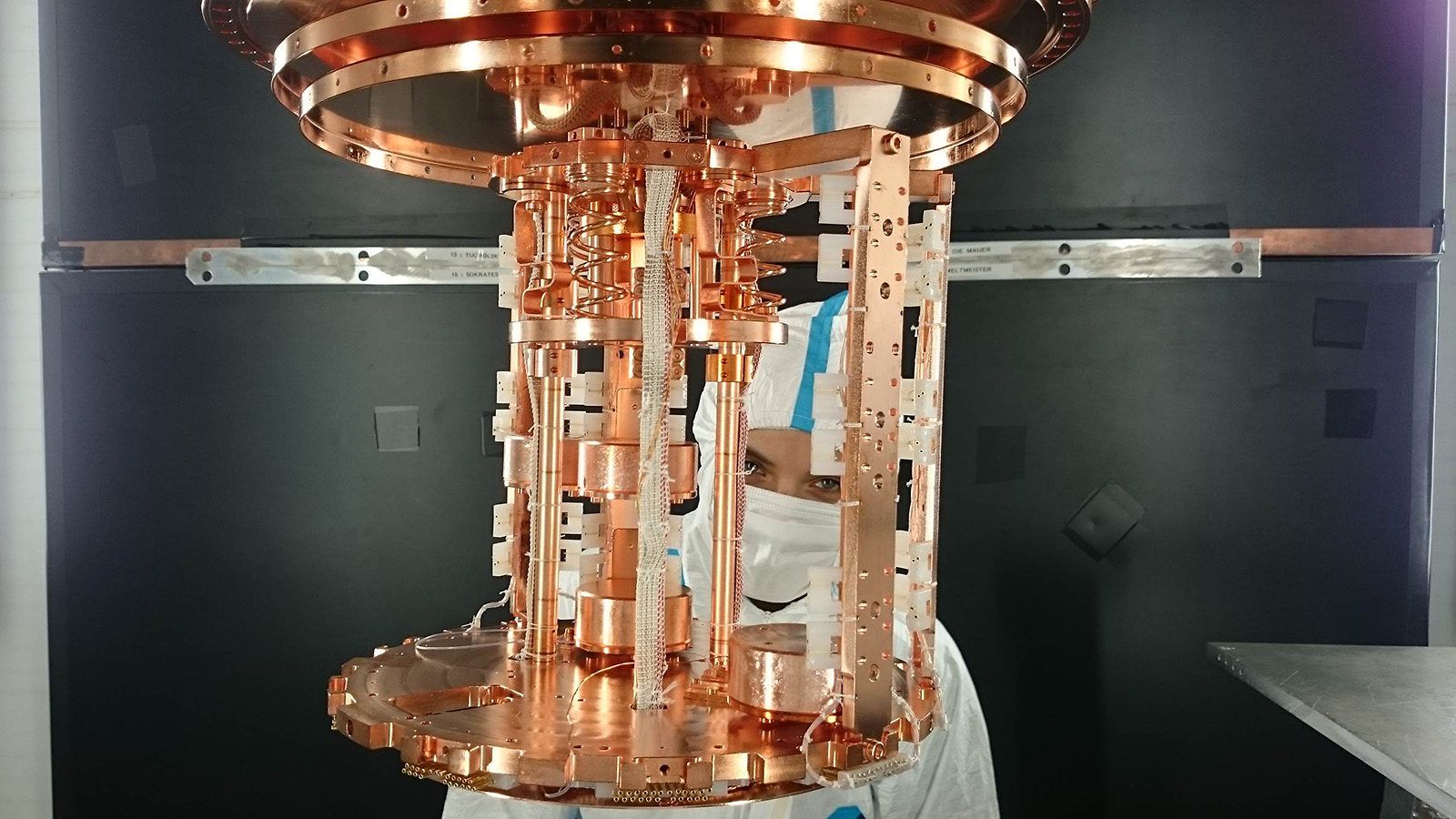

Given that genetic science hasn’t worked through a way to rewire the human brain, Marcus poses that better solution toward cognitive enhancement might be found in implants. Rather than generations from now, he believes that advancement could happen in our lifetimes.

“There are now actual cognitive enhancements, if you count motor control substitutes. Neural prostheses are here in limited ways. We know roughly how to make them. There’s a lot of fine detail that needs to be sorted,” Marcus said. “We certainly know how to write computer programs that can translate between interfaces. The big limiting step in improving our memory or enhancing our memory is, we just don’t really understand how information is stored in the brain. I think (a solution for that) is a 50-year project. It’s certainly not a 50,000 year project.”