Tesla CEO Elon Musk, speaking at the Hyperloop Pod Competition this week, said he has been thinking more and more about electric jets.

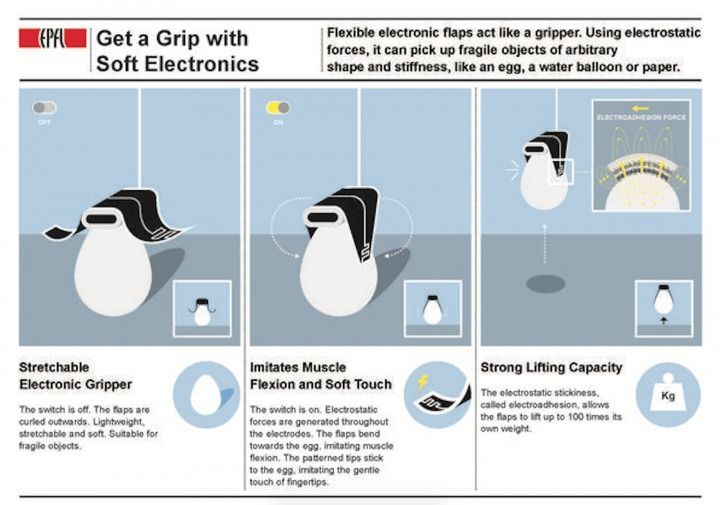

Robots aren’t exactly known for their delicate touch, but soon, the stereotype of the non-gentle machine may change. Scientists say they have managed to develop a robot with “a new soft gripper” that makes use of a phenomenon known as electroadhesion — which is essentially the next best thing to giving robots opposable thumbs. According to EPFL scientists, these next-gen grippers can handle fragile objects no matter what their shape — everything from an egg to a water balloon to a piece of paper is fair game.

This latest advance in robotics, funded by NCCR Robotics, may allow machines to take on unprecedented roles. “This is the first time that electroadhesion and soft robotics have been combined together to grasp objects,” said Jun Shintake, a doctoral student at EPFL. Potential applications include handling food, capturing debris (both in space and at home), or even being integrated into prosthetic limbs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQtQGoMRXaI

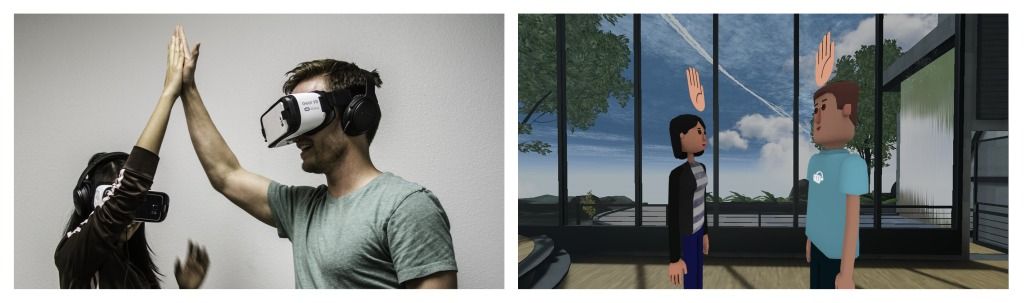

Virtual reality can sometimes appear like it’s a pretty isolating platform. Visually, people experiencing VR certainly aren’t in the most approachable position and right now the tech is new enough that it rarely seems accessible to those who are vaguely curious.

That being said, there are plenty of companies succeeding in strengthening the social potential of VR. One of the coolest companies doing so, AltspaceVR, just became even more accessible today as it launched its mobile experience on Samsung Gear VR.

“I know that you’re a computer-generated image, but your smell, your touch, the way you feel, even the things you say and think seem so real.” — Commander William Riker.

Serious Wonder looks at various episodes of Star Trek to unlock their future-oriented humanist philosophy. — B.J. Murphy for Serious Wonder.

At Singularity University, space is one of our Global Grand Challenges (GGCs). The GGCs are defined as billion-person problems. They include, for example, water, food, and energy and serve as targets for the innovation and technologies that can make the world a better place.

You might be thinking: We have enough challenges here on Earth—why include space?

We depend on space for telecommunications, conduct key scientific research there, and hope to someday find answers to existential questions like, “Are we alone in the universe?”. More practically, raw materials are abundant beyond Earth, and human exploration and colonization of the Solar System may be a little like buying a species-wide insurance policy against disaster.

It takes 100 attoseconds for a krypton electron to respond to light. That might not seem like much, but someday it could limit the speed of optoelectronic circuits.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CQtQGoMRXaI

AltspaceVR lets you share experiences with people in virtual reality. Hang out, attend events, play games, and more.

Join the community (no headset required): https://account.altvr.com/users/sign_up

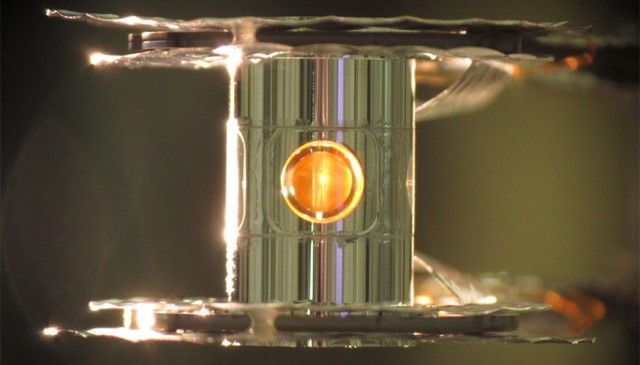

Physicists in England claim they have discovered how to create matter from light, by smashing together individual massless photons– a feat that was first theorized back in 1934, and has been considered practically impossible until now. If this new discovery pans out, the final piece of the physics jigsaw puzzle that describes how light and matter interact would be complete. No one’s quite sure of the repercussions if matter can indeed be produced from photon-photon collision, but I’m sure something awesomely scientific will emerge before long.

Way back in 1930, British theoretical physicist Paul Dirac theorized that an electron and its antimatter counterpart (a positron) could be annihilated (combined) to produce two photons. Then, in 1934, two physicists — Breit and Wheeler — proposed that the opposite should also be true: That two photons could be smashed together to produce an electron and positron (a Breit-Wheeler pair). In other words, that light can be converted into matter, and vice versa — or, to phrase it another way, E=mc2 works in both directions. This would close one of the last gaps in particle physics that has been theorized, but has proven very hard to prove through observation.